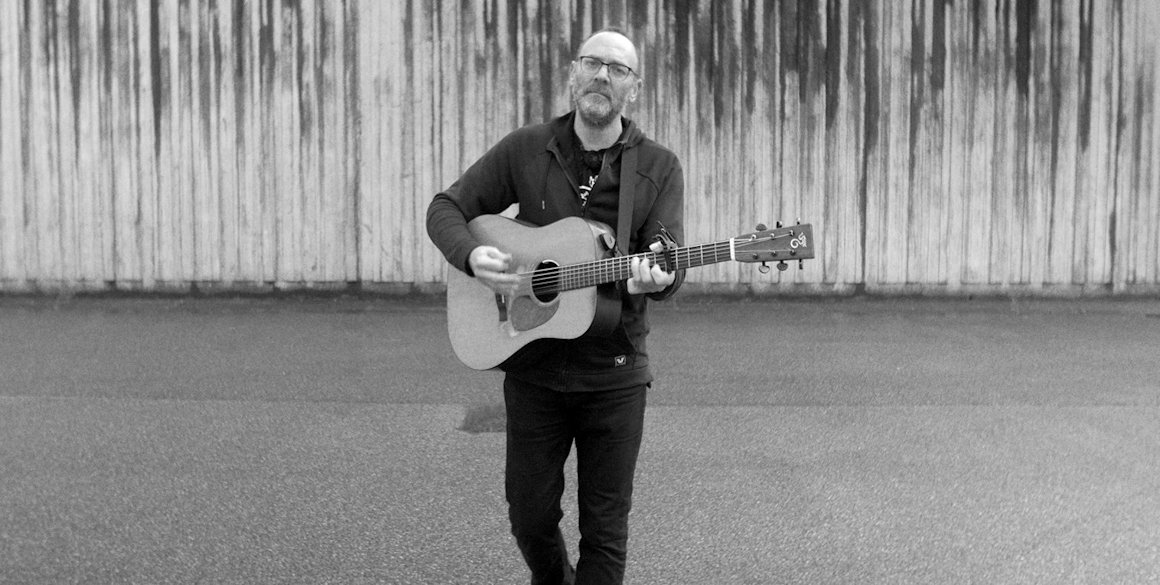

Instrumental music for activists

When thinking of the kind of music used in struggles for social justice, most people probably think of music with lyrics. Over the past fifteen years, Stefan Christoff, a Montreal-based musician and activist, has been exploring something different: the role of instrumental music as a force to unite people and cultivate transformative visions. Christoff seeks to create instrumental music that nurtures the “dream-based and imaginative zone” of activism, and sustains the energy and mental health of activists. Stefan Christoff first began working as a musician in solidarity with Montreal anti-poverty groups in the late 90’s. The scope of his work expanded when he organized concerts for activists during the Summit of the Americas in Quebec City in the spring of 2001. Since then, his artistic projects have included organizing Artists Against Apartheid concerts in solidarity with Palestine, as well as concerts in solidarity with indigenous struggles and migrant workers. Recommended recordings include: ‘Duets for Abdelrakik’; ‘Regard sur le 7e feu’, and ‘Flying Street’ (with Egyptian-Canadian musician Sam Shalabi). Check out Stefan Christoff’s music at http://soundcloud.com/spirodon.

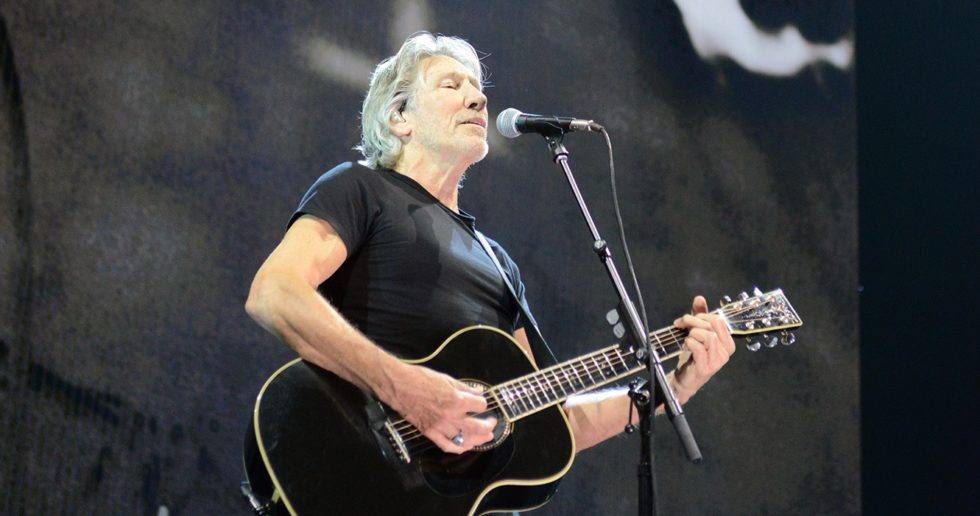

Ron Hynes: ‘Man of a Thousand Songs’

Newfoundland is a province with a famously rich musical culture, both past and present. It comes as a surprise therefore, to discover that Ron Hynes, the beloved singer-songwriter who died on November 19, was the first Newfoundland musician to release an album composed of totally original content (Discovery, released in 1972). Hynes was born in 1950 in St. John’s and raised in the outport of Ferryland. During his long career he won many awards and distinctions, first as an East Coast artist, then nationally, and ultimately internationally. His songs have been recorded by more than 100 artists, including Emmylou Harris and Christie Moore. Ron Hynes was so warmly embraced in his home province because his many poignant and beautifully-crafted songs explore experiences common to several generations of Newfoundlanders. As is the case with much great folk music, his broad appeal is directly related to those local stories. The affection in which he is held was evident in the outpouring of tributes at his statue in downtown St. John’s and in the public Music singalongs of his famous song “Sonny’s Dream”. That song is a good place to start if you’re new to Ron Hynes. Recommended also is the 2012 CBC documentary Ron Hynes: Man of a Thousand Songs.

Highlights from the Latin Grammys

Mexican rock band Maná, one the most popular groups in the Spanish-speaking world, and Los Tigres del Norte, long considered the voice of the Mexican community in the U.S., joined forces at the Latin Grammys on November 19 to perform the Tigres’ pro-migrant song “Somos Más Americanos”. It’s worth looking up the English lyrics to this proud anthem to appreciate the political nature of their performance, coming as it does after recent outbursts of racist, anti-immigrant rhetoric by politicians, notably Republican presidential front-runner Donald Trump. At the song’s end, with the audience cheering, the musicians unveiled a banner that read “Latino unidos, no voten por los racistas” (“Latinos united don’t vote for the racists”). The action was well-timed to coincide with an online Latino voter registration campaign. In other news, Cuban music fans had plenty to cheer about at the glitzy Las Vegas event. Best Video award went to Cuban maestro Silvio Rodriguez and Puerto Rican duo Calle 13 (“Ojos Color Sol”), Septeto Santiaguero won for Best Traditional Tropical Album (“No quiero llanto/Tributo a los Compadres”), and Cuban trova maestro Pablo Milanés received a lifetime achievement award.

The ‘audiopolitics’ of Noise Uprising

Verso Books has published an important new book on music by the American cultural historian Michael Denning. Noise Uprising: The Audiopolitics of a World Music Revolution is a study of the sound revolution that took place between 1925 and the onset of the Great Depression, a time when record companies from the imperial metropolises recorded musicians in colonial port towns and released millions of 78 rpm shellac discs for both local and international consumption. Although the first electronic recording boom fizzled out during the early thirties, it nurtured a revolution in the craft of music-making, as well as in musical tastes. While folklorists of the day argued about the purity as “folk music” of the recordings that local urban musicians made in New Orleans, Havana, Buenos Aires, Rio de Janeiro, Cairo, Shanghai, and elsewhere, these same recordings, with their non-European timbres and rhythms, challenged the musical orthodoxy of the colonial overlords, and were celebrated as subversive by many local revolutionaries. Denning makes a fascinating case for a ‘decolonizing of the ear’ – one that preceded the political decolonization that came after World War II. Noise Uprising is rightly being hailed as a classic. (Added bonus: a playlist of recordings mentioned in the book can be streamed for free on Spotify.)