150 years of the Red River Resistance

As we watch protests across the US against the racist cop murder of George Floyd, it’s important to remember that racist repression is not “an American thing.” It is true that the US had a much longer history of chattel slavery (“de jure” or legalized slavery); but Canada also has a history of slavery, mass killings, police murders, forced assimilation and systemic racism.

One example of this is the residential school system, an official policy spanning over a century, designed to destroy the culture and identities of Indigenous peoples. It was a policy that fits the definition of genocide in the United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. The physical annihilation of the Beothuk people, the spread of smallpox, the hanging of six Tsilqot’in chiefs in 1864, the stunning over-representation of Indigenous people in the Canadian penitentiary system, the refusal by police to seriously investigate the murders of Indigenous woman and girls – these are just a few other examples.

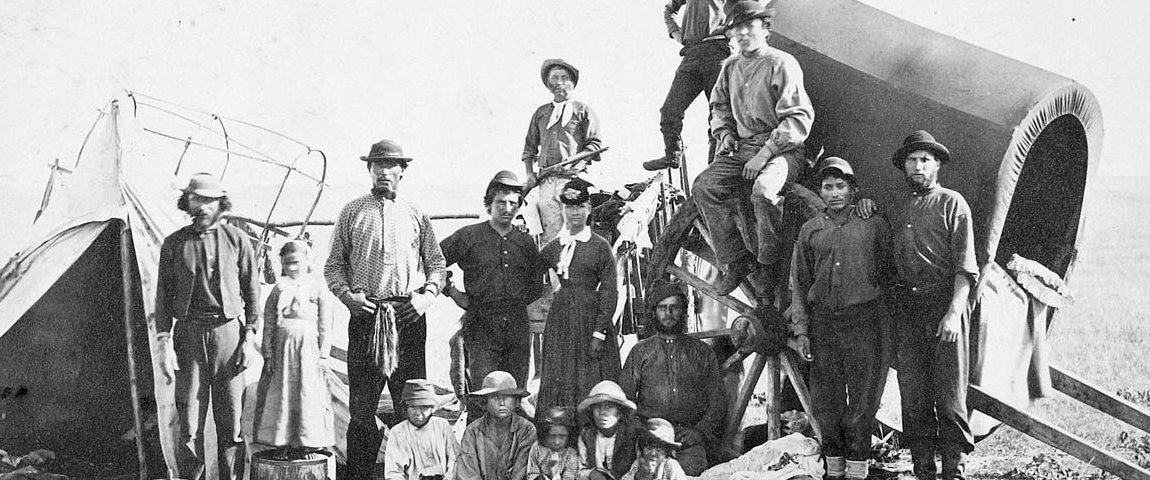

Another is the period of violent ethnic cleansing after Manitoba became the fifth province of Canada in 1870. The events were set in motion by the agenda of the new Canadian government to turn the Red River area into a primarily Anglophone and Protestant territory, forming a barrier against northward expansion of the United States, and a political counter-balance to French-speaking, Catholic Quebec. At the time of Confederation in 1867, the population of the areas around present-day Winnipeg were primarily the two groups of French- and English-speaking Métis hunters and farmers (who already had a long history as a distinct nation), as well as the original inhabitants – the Indigenous peoples among whom voyageurs and fur traders had intermarried over the previous two centuries – and a much smaller number of “Canadian” colonists settled in the area by Lord Selkirk in 1812 and later. (Many of these settlers had been driven off their lands in the infamous Highland clearances.)

Parts of this story are widely-known, but completely distorted by reactionary writers and even by “objective” sources such as the online Canadian Encyclopedia. The real facts are in Jean Teillet’s recent book, The North-West Is Our Mother, reviewed in the previous issue of People’s Voice.

In 1869, survey crews arrived in the Red River area, sent by the Canadian government. Despite Conservative Prime Minister John A. Macdonald’s vague promises to protect the rights of the Métis, the crews’ task was to prepare for a radical change in land use and ownership. The river-lot farms established by the Métis, well-suited to their economy and culture, were to be replaced by the square-block pattern of farms and made available for a new wave of English-speaking settlers. The transition was part of an intense struggle between Britain, Canada and the US over Rupert’s Land, the vast territory granted by the British crown to the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) in 1670.

When the HBC agreed to surrender its monopoly over Rupert’s Land and the North West (including the Red River area), growing numbers of Anglo settlers from Ontario began moving in, along with land speculators. Naturally, the Métis began organizing to preserve their land rights and culture. Louis Riel, a young Montreal-educated Métis from a prominent family in the community, emerged as a powerful leader.

What followed is called the Red River Rebellion by bourgeois historians but, in reality, there was no government to rebel against. From about 1820-1870 the region was administered by the Council of Assiniboia, an appointed body largely controlled by the HBC. The Métis people also had their own Council of the Hunt, to oversee the semi-annual buffalo hunts which were key events in their lives.

In early 1870, the population elected a Provisional Government, led by Riel, to negotiate a deal with Canada. As tensions grew, the Provisional Government executed a prisoner being held for his attempts to murder Riel. This was Thomas Scott, a fanatic reactionary intent on driving the Métis out of Red River. Meanwhile, Canada sent a thousand-man Expeditionary Force – mostly volunteers who were members of the Orange Order, the notorious racist gang known for murderous anti-Catholic pogroms in the Protestant enclave of Northern Ireland.

The federal “Manitoba Act” came into effect on May 12, 1870 and provided terms to protect French-language rights in the new province’s legislature and courts, as well as Protestant and Roman Catholic educational rights. 1,400,000 acres of land were set aside for the Métis, and the province received four seats in Parliament. The Métis regarded the Act as a treaty with Canada. But Macdonald and his Orange Order brutes were determined to change these terms by force. Riel was elected to Parliament three times but was never allowed to take his seat.

A reign of terror was launched, starting with Orange Order “indignation meetings” across Ontario to stir up anti-Métis and anti-French bigotry. The Expeditionary Force finally arrived in August 1870, becoming an occupation army seeking revenge for the death of Thomas Scott. Young Métis men were assaulted in public, houses were raided and torched, women were raped in their homes. Riel became a marked man, as were other members of the disbanded Provisional Government, some of whom were killed. Newspapers which supported Métis rights were closed.

After the two-year contracts signed by the volunteers expired in the spring of 1871, the level of violence committed by these new “civilians” escalated. The perpetrators went unpunished, despite some conciliatory tactics by new Lieutenant-Governor of Manitoba Adams George Archibald, who Macdonald soon replaced. The Prime Minister remained silent as the reign of terror continued for two-and-a-half years. Not even the crucial Métis role in blocking the Fenian Raids of 1871 – saving Manitoba from a US takeover – won them any favours from Canada.

With no hope of gaining title to the lands promised by the Manitoba Act, much of the Métis community relocated, to safer places further west and north. A decade later, the surveyors were back. The North-West Resistance of 1885 ended with military defeat at Batoche, the state-sanctioned murder of Riel and a new scattering of the people.

The Métis Nation’s legal and political struggle to win compensation for their stolen lands continues to this day. On the 150th anniversary of the Red River Resistance, as it’s properly known, the Canadian state must be held accountable for the killings and violence committed by its troops during the murderous ethnic cleansing of 1870-1872.

[hr gap=”10″]

Support socialist media!

If you found this article useful, please consider donating to People’s Voice.

We are 100% reader-supported, with no corporate or government funding.