Helen Yaffe

COVID-19 emerged in the Chinese city of Wuhan in late December 2019, and by January 2020 it had hit Hubei province like a tidal wave, swirling over China and rippling out overseas.

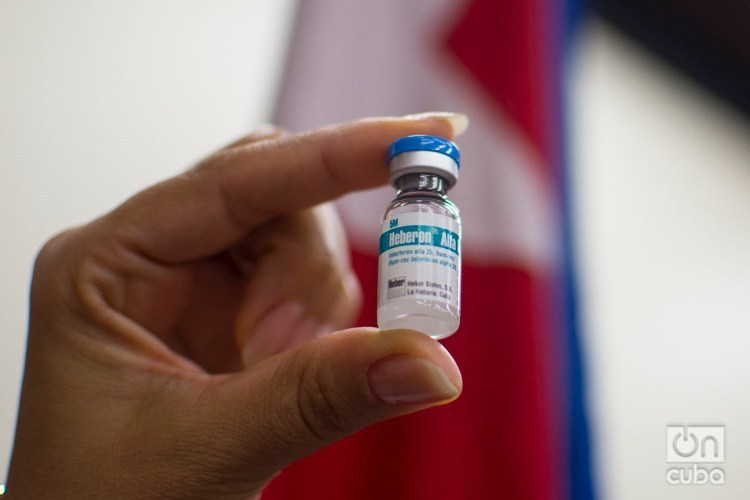

The Chinese state rolled into action to combat its spread and care for those infected. Amongst the 30 medicines chosen by the Chinese National Health Commission to fight the virus was a Cuban anti-viral drug called Interferon Alfa-2B, which has been produced in China by the Cuban-Chinese joint venture ChangHeber since 2003.

Interferon Alfa-2B and Cuban biotechnology

Cuban Interferon Alfa-2B has proven effective for viruses with characteristics similar to those of COVID-19. Cuban biotech specialist Dr Luis Herrera Martínez explains that “its use prevents aggravation and complications in patients, reaching that stage that can ultimately result in death.”

Cuba first developed and used interferons to arrest a deadly outbreak of the dengue virus in 1981, and that experience catalysed the development of the island’s now world-leading biotech industry.

The world’s first biotechnology enterprise, Genetech, was founded in San Francisco in 1976, followed by AMGen in Los Angeles in 1980. One year later, the Biological Front, a professional interdisciplinary forum, was set up to develop the industry in Cuba.

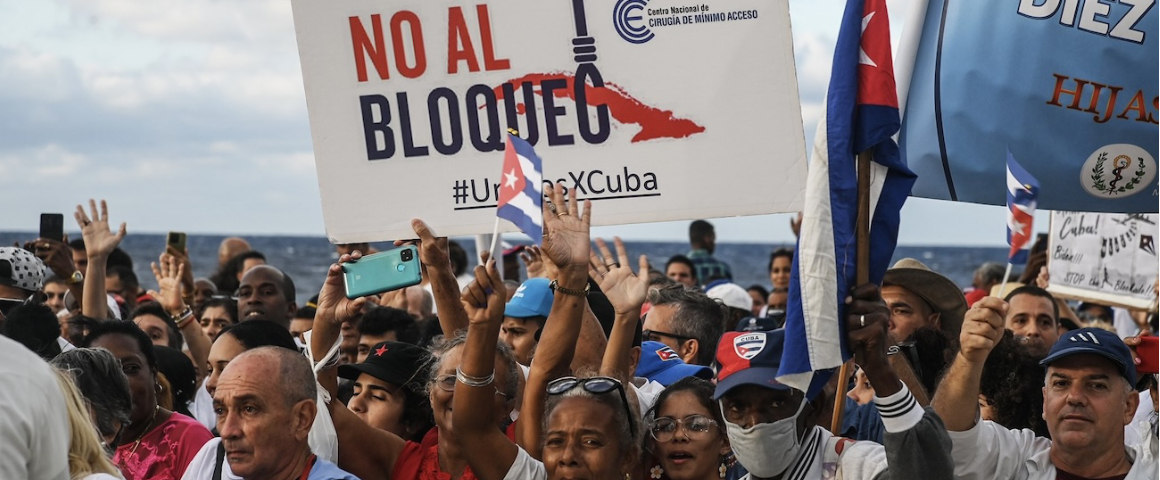

While most developing countries had little access to new technologies (recombinant DNA, human gene therapy, biosafety), Cuban biotechnology expanded and took on an increasingly strategic role in both the public-health sector and the national economic development plan. And this despite the US blockade, which obstructed access to technologies, equipment, materials, finance, and even knowledge exchange. Driven by public-health demand, it has been characterized by its fast track from research and innovation to trials and application, as the story of Cuban interferon shows.

The international history of Cuban interferons

Interferons are “signalling” proteins produced and released by cells in response to infections in order to prompt nearby cells to heighten their anti-viral defences. They were first identified in 1957 by Jean Lindenmann and Aleck Isaacs in London. In the 1960s, Ion Gresser, a US researcher in Paris, showed that interferons stimulate lymphocytes that attack tumours in mice. In the 1970s, US oncologist Randolph Clark Lee took up this research.

The first international event in 1983 was prestigious; Cantell gave the keynote speech and Clark attended with Albert Bruce Sabin, the Polish American scientist who developed the oral polio vaccine.

Convinced about the contribution and strategic importance of innovative medical science, the Cuban government set up the Biological Front in 1981 to develop the sector. Cuban scientists went abroad to study, many in western countries. Their research took on more innovative paths, as they experimented with cloning interferon.

By the time Cantell returned to Cuba in 1986, the Cubans had developed the recombinant human Interferon Alfa 2B, which has benefited thousands of Cubans since then. With significant state investment, Cuba also opened its showpiece Centre for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (CIGB) in 1986. But by then Cuba was submerged in another health crisis, a serious outbreak of meningitis B, though this too served to stimulate Cuba’s biotechnology sector.

Cuba’s meningitis miracle

In 1976, Cuba was struck by outbreaks of meningitis types B and C. Prior to that, only a few isolated cases had been seen on the island. Internationally, vaccines existed for meningitis types A and C, but not for type B.

Cuban health authorities secured a vaccine from a French pharmaceutical company to immunize the population against type C meningitis. However, in the following years, cases of type B began to rise. A team of specialists from different medical science centres was established, led by a woman biochemist, Concepción Campa, to work intensively on finding a vaccine.

By 1984, meningitis B had become the most serious health problem in Cuba. After six years of intense work, Campa’s team produced the world’s first successful meningitis B vaccine in 1988. A member of Campa’s team, Dr Gustavo Sierra recalled their joy: “This was the moment when we could say it works, and it works in the worst conditions, under the pressure of an epidemic and amongst people of the most vulnerable age.”

Between 1989 and 1990, the three million Cubans most at risk were vaccinated. Subsequently, 250,000 young people were vaccinated with the VA-MENGOC-BC vaccine, a combined vaccine for meningitis types B and C. The vaccine recorded a 95 per cent efficacy rate overall, with 97 per cent in the high-risk age group of three months to six years. Cuba’s meningitis B vaccine was awarded a UN Gold Medal for global innovation. This was Cuba’s meningitis miracle.

Recalling a chart of the rise and sudden fall of meningitis B cases in Cuba, the Director of the Centre for Molecular Immunology (CIM) Agustín Lage told me, “one can work 30 years, 14 hours a day, just to enjoy that graph for 10 minutes … Biotechnology started for this. But then the possibilities of developing an export industry opened up, and today Cuban biotechnology exports go to 50 countries.”

Since its first application to combat dengue fever, Cuba’s interferon has shown its efficacy and safety in the therapy of viral diseases including hepatitis types B and C, shingles, HIV-AIDS, and dengue. Because it interferes with viral multiplication within cells, it has also been used in the treatment of different types of carcinomas. Only time will tell if Interferon Alfa 2B proves to be the wonder drug in tackling COVID-19.

Helen Yaffe is a lecturer in economic and social history at the University of Glasgow, specializing in Cuban and Latin American development. This article is republished from the LSE Latin America and Caribbean blog.