Folksinger Woody Guthrie (1912-1967) is widely acclaimed as the great bard of the American working class. More than fifty years after his death, his songs are still performed around the world. Guthrie grew up in Okemah, Oklahoma, in the heart of Cherokee territory. So, when a young Indigenous musician raises questions about Woody’s most celebrated song, “This Land Is Your Land,” it’s an invitation to think about his life and examine the assumptions of earlier generations of progressive artists. Guthrie wrote “This Land Is Your Land” in 1940 as a riposte to popular singer Kate Smith’s recording of Irving Berlin’s jingoistic World War I song, “God Bless America.” Rather than a flag-waving, patriotic song, Woody, who was a communist, wanted a song that celebrated working people and criticized the capitalist system.

Indigenous singer Mali Obomsawin, a member of the Abenaki First Nation, criticized the song in a June 14 article, “This Land Is Whose Land?” published by the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage (www.folklife.si.edu). For Obomsawin, “This Land” falls flat. “In the context of America, a nation-state built by settler colonialism, Woody Guthrie’s protest anthem exemplifies the particular blind spot that Americans have in regard to Natives: American patriotism erases us, even if it comes in the form of a leftist protest song.”

Obomsawin also states that “since its conception, the song’s more radical verses critiquing capitalism and exclusionism have fallen by the wayside,” leaving it “merely patriotic.” She’s right about that. Guthrie’s original recording contains anti-capitalist verses, but those lines never made it into the schoolbooks when the song became canonized: As I went walking, I saw a sign there / And on the sign it said, “No Trespassing.” / But on the other side it didn’t say nothing / That side was made for you and me / In the squares of the city, in the shadow of a steeple / By the relief office, I’d seen my people / As they stood there hungry, I stood there asking / Is this land made for you and me? / Nobody living can ever stop me / As I go walking that freedom highway / Nobody living can ever make me turn back / This land was made for you and me.

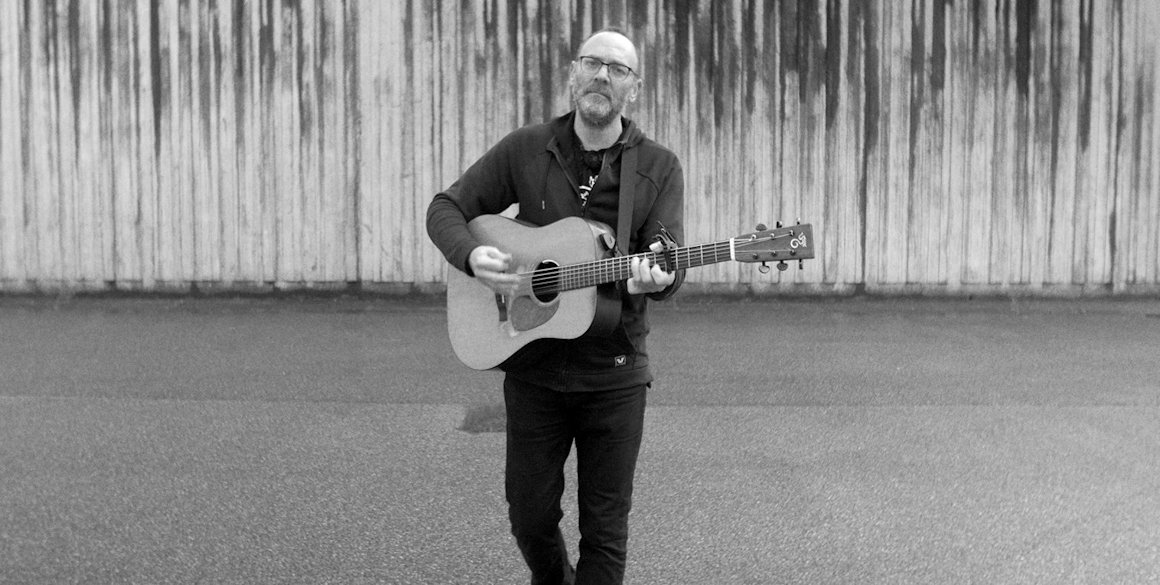

Will Kaufman, Professor of American Literature and Culture at the University of Central Lancashire, and author of three books on Woody Guthrie, responded to Obomsawin in an August 20 article, “The Misguided Attacks on ‘This Land Is Your Land’,” originally published at The Conversation (www.theconversation.com). Kaufman maintains that Guthrie was outraged by America’s genocidal history. He informs us that Woody was angry with his cousin, country singer “Oklahoma Jack” Guthrie, not only for claiming credit for Woody’s song “Oklahoma Hills”, but for cutting out “the best parts of the whole song” – the names of “the Chickasaw, Choctaw, Cherokee, Creek and Seminole” who had prior claim to the lands of Oklahoma. In a 1949 live recording, Guthrie tells his audience, “They used dope, they used opium, they used every kind of trick to get [Indigenous people] to sign over their lands.”

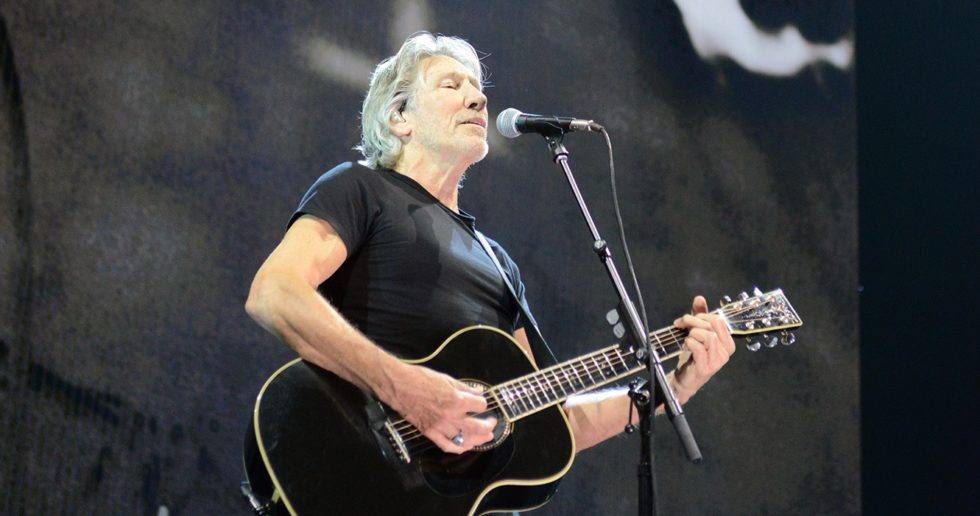

Woody’s friend, Pete Seeger was in later years sensitive to criticisms of the song. He would sometimes add a verse written by activist Carolyn “Cappy” Israel: This land is your land, but it once was my land / Before we sold you Manhattan Island / You pushed my nation to the reservation / This land was stole by you from me. Perhaps in time Woody might himself have composed verses for “This Land Is Your Land” that addressed the dispossession issue. But he did not have much time left; by the early 1950’s a debilitating and deadly disease – Huntington’s Chorea – had sidelined and effectively silenced him.

Kaufman cites several Indigenous artists who have recorded Guthrie’s songs in recent years. In 2006, Blackfire, a Navaho band from Arizona, recorded two previously unpublished Guthrie songs – “Indian Corn Song” and “Mean Things Happenin’ in This World.” In 2007, Anishinaabe singer Keith Secola recorded an Ojibwa version of “This Land” on his album “Native Americana – A Coup Stick,” and acknowledged in an interview the songwriting lessons he had learned by listening to Woody’s songs. Indigenous artists like Secola and Blackfire, Kaufman suggests, are essentially saying “Woody Guthrie might not have been perfect, but we don’t need to “cancel” him. We’ll work with him instead.”