The mainstream parties in the 2019 federal election are all, it seems, claiming to be feminist. But are they really committed to implementing programs that will help achieve equality for women and gender oppressed people?

Here, we look at the gender wage gap and ask, “Why hasn’t this been closed?”

On International Women’s Day in 2016, Justin Trudeau famously declared, “I myself am a feminist.” When Andrew Scheer was asked by Maclean’s magazine, shortly after winning the Conservative Party leadership, if he was a feminist, he responded, “Yeah, absolutely!” Elizabeth May regularly seasons her tweets with the phrase, “as a feminist…” Jagmeet Singh has identifed himself as a “feminist ally.”

So, with all this feminism, regardless of who gets elected should we expect to see great strides toward women’s equality and equality for all gender oppressed people? That hardly seems likely.

But to think scientifically about election promises for achieving gender equality, we can start by confronting one of the key measures of inequality.

Wage inequity

One of the most widely recognized indicators of inequality for women is the gender wage gap. Also called the gender pay gap or the gender earnings gap, it is the difference between what women and men are paid. Despite the fact that pay equity has been part of the law in Canada since the 1977 Canadian Human Rights Act, women continue to be paid significantly less than men.

How much less depends on how the wage gap is measured.

The Canadian Women’s Foundation has noted that there are three main ways of measuring the gender wage gap. These can be summarized as follows:

Compare the hourly wages of full-time working women to those of men. This measurement shows that women earn roughly 87 cents for every dollar earned by a man (2015 data). This method deliberately excludes part-time working women; Statistics Canada argues that full-time working women tend to work fewer hours than men, so this measurement provides a more precise picture of the wage gap.

Compare the annual earnings of full-time workers. Using this method, women workers earn approximately 75 cents for every dollar earned by men (2016 data). This is a more inclusive measurement than the first method, by looking at annual earnings. However, it still excludes part-time women workers, which is a particularly large group.

Compare the annual earnings for both full-time and part-time workers. By this measurement, women earned an average of 69 cents for every dollar earned by men in 2016. This method is the most comprehensive of the three, because it includes the reality that more women work part-time, and that part-time workers are generally lower paid that their full-time equivalents.

Notably, regardless of the comparison method used women experience a wage gap of at least 13% and as high as 31%. More importantly, as the measurement becomes more comprehensive – by including a more inclusive scope of women’s work experience – the gap gets much larger.

A report from Statistics Canada noted that from 1981 to 2018, the gender wage gap decreased by 21%. This means it took 37 years for the wage gap to decrease by one-fifth – at this rate, it will take 139 years for the gap to be closed. And this is only the gap for full-time working women.

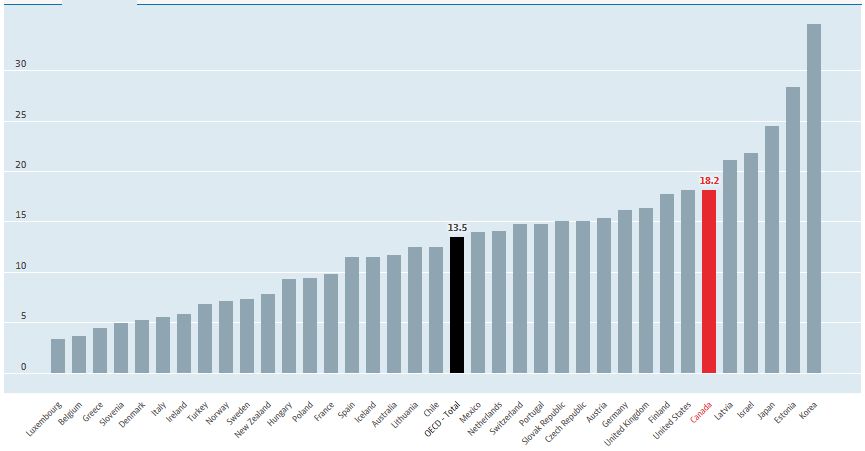

Internationally, Canada is doing terribly at closing the wage gap. A recent report from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development shows that, out of 35 OECD countries Canada ranks 30th, sixth last.

Putting a dollar figure on the gender wage gap is a bit tricky, but there are statistics we can use. According to StatsCan, there were 15.8 million people working in Canada in 2018, of whom 7.8 million were women. That same year, the average weekly wage was $984 or $51,168 per year. This means that total annual earnings among all workers were somewhere around $808 billion. Using the overall annual earnings gap of 31%, we can calculate that men earned around $478 billion of this amount and women earned around $330 billion.

That’s $148 billion in lost wages for women. Every year.

Of this amount, roughly $112 billion is from the private sector, where 76% of workers are employed. This suggests that the gender wage gap provides over $100 billion in annual corporate profit. It’s an indication of how deeply the gender wage gap is rooted in, and reinforces, the gender division of labour within capitalism.

All of the above reflects a simplified gender binary approach – men and women – which illustrates the general trends but misses the experience of specific groups. Indigenous women working full-time are paid only 65 cents for every dollar paid to non-Indigenous man, and full-time racialized women receive 67% of the pay of non-racialized men (2016 data). A 2012 survey found that the wage gap experienced by disabled women working full- or part-time was an enormous 54%. Transgender and gender nonconforming folks also experience increased wage discrimination: data from 2012 indicates that the average earnings of a transgender woman decrease by over 30% after she transitions. In examining the pay gap, it’s important to recognize the layering of gender, racialization, homophobia and transphobia, and disability injustice.

The wage gap has long-ranging effects. Immediately, it contributes directly to the disproportionate number of women who live in poverty – a 2018 study showed that of the nearly 6 million people who are struggling financially in Canada, 60% are women. This, in turn, tends to affect child poverty, as the number of lone-parent families is increasing and over 80% of such families are headed by women. Lower pay also means lower contributions to retirement plans, including the Canada Pension Plan, which leaves a disproportionate number of senior women living in poverty.

Low income and poverty also affect women’s safety. Studies show that women who are in abusive relationships will sometimes stay in those relationship because of economic precarity. It is a fact that women who leave a relationship and raise children on their own are much more likely to end up living in poverty.

Waiting another 139 years is simply unacceptable – closing the gender wage gap requires decisive government intervention. Consider that while Canada’s military budget, used to enforce US-NATO economic and political interests across the globe, is approach $32 billion per year, the total budget for the Human Rights Commission, of which pay equity enforcement is a component, is only $28 million. Or compare the amount of public resources that are committed to enforcing individual taxation, whether through income or sales taxes, with the meagre effort dedicated to stopping the $148 billion annual wage theft from working women.

There is no comparison. Wage equity is simply not a priority for the government. Why? Because inequality pays.

Women’s organizations have fought for decades to close the gender wage gap. Their struggles have won gains, but it will take the whole working class, united with its allies, to win this fight.

We can start by making concrete and uncompromising demands on candidates and parties in this federal election.

Elizabeth Rowley, leader of the Communist Party, says that one of the first tasks is to create good jobs. “Adopting a full-employment strategy, and replacing precarious work with well-paid permanent jobs, is an urgent necessity. Combining this with a $20 minimum wage and increased EI benefits, along with real action to close the gender wage gap, would mean a huge step forward in terms of women’s equality and equality for all gender oppressed people.”