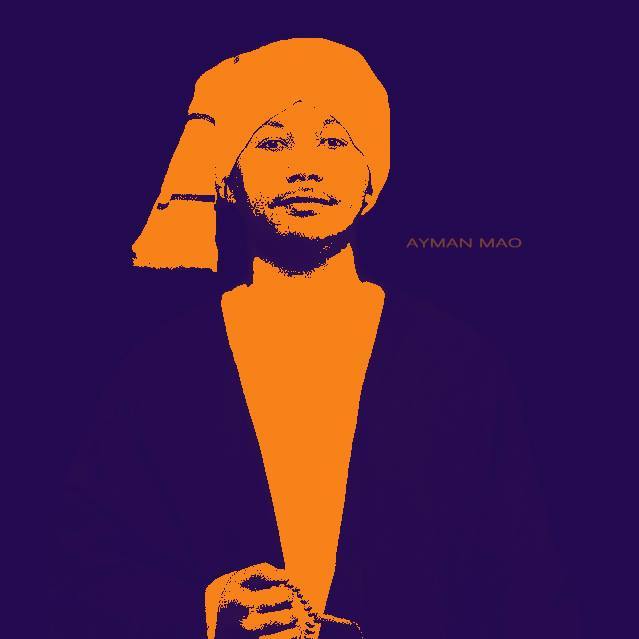

There are times when, in the midst of a democratic struggle, an artist appears who expresses the aspirations and the anger of the people. The Sudanese rapper Ayman Mao is one such artist. His song “Dum” (“Blood”) is widely recognized as an anthem of Sudan’s democratic revolution. The popularity of Mao was evident at an evening concert he gave on April 25 before tens of thousands of protesters outside the Sudanese army’s headquarters in Khartoum. As he chanted the verses of “Dum” (“Live ammunition / And they tell you it’s a rubber bullet”) the crowd, waving illuminated cell-phones, responded “Thawra!” (“Revolution!”). Ayman Mao was a musician and political activist in Khartoum before moving to study in the USA in 2009. After receiving his MBA he found work in Dallas, but continued to write and release songs. When mass protests against long-time Sudanese dictator Omar al-Bashir broke out in December, Mao performed at solidarity gatherings in American Sudanese communities. Then he discovered that his recording of “Dum” had become a popular symbol of the revolution. After Bashir fell on April 11, Mao booked a flight to Khartoum. Arriving on April 25, he proceeded directly to the sit-in outside army headquarters, where a stage had been set up for what has been called the largest concert in Sudan’s history.

There are times when, in the midst of a democratic struggle, an artist appears who expresses the aspirations and the anger of the people. The Sudanese rapper Ayman Mao is one such artist. His song “Dum” (“Blood”) is widely recognized as an anthem of Sudan’s democratic revolution. The popularity of Mao was evident at an evening concert he gave on April 25 before tens of thousands of protesters outside the Sudanese army’s headquarters in Khartoum. As he chanted the verses of “Dum” (“Live ammunition / And they tell you it’s a rubber bullet”) the crowd, waving illuminated cell-phones, responded “Thawra!” (“Revolution!”). Ayman Mao was a musician and political activist in Khartoum before moving to study in the USA in 2009. After receiving his MBA he found work in Dallas, but continued to write and release songs. When mass protests against long-time Sudanese dictator Omar al-Bashir broke out in December, Mao performed at solidarity gatherings in American Sudanese communities. Then he discovered that his recording of “Dum” had become a popular symbol of the revolution. After Bashir fell on April 11, Mao booked a flight to Khartoum. Arriving on April 25, he proceeded directly to the sit-in outside army headquarters, where a stage had been set up for what has been called the largest concert in Sudan’s history.

A little background is in order here. Since April 11, Sudan has been ruled by a Transitional Military Council (TMC). It’s promised a three-year transition to civilian rule. TMC President Abdel Burhan is seen by some as a mere figurehead, with real power exercised by Vice-President General Mohamad Dagalo, leader of the notorious Rapid Support Force. The Alliance for the Forces of Freedom and Change is the main political force representing the people confronting the TMC. Since April, the Alliance has led demonstrations calling for the TMC’s dissolution and an immediate transition to civilian rule. It is in this context that Mao’s “Dum” gets to the crux of the matter. When he declares that those who are firing live ammunition at peaceful protesters are “Janjaweed thugs” he’s pointing out the connections between General Dagalo’s Rapid Support Force and the Janjaweed militia, a government force that carried out well-documented atrocities against civilians during the Darfur conflict in Western Sudan more than a decade ago. On July 6, a power-sharing deal was announced between the TMC and the Alliance. Full details are still emerging, but many observers are skeptical, given the disappointing experiences of “Arab Spring” uprisings in the Middle East and North Africa over the past decade. Meanwhile, Ayman Mao is back in in the USA, saying “I am confident we will win in the end; they cannot trick the Sudanese people anymore”.

Let’s hope he’s right. Imperialism can be pretty tricky.

New Orleans Pays Tribute to Dr. John

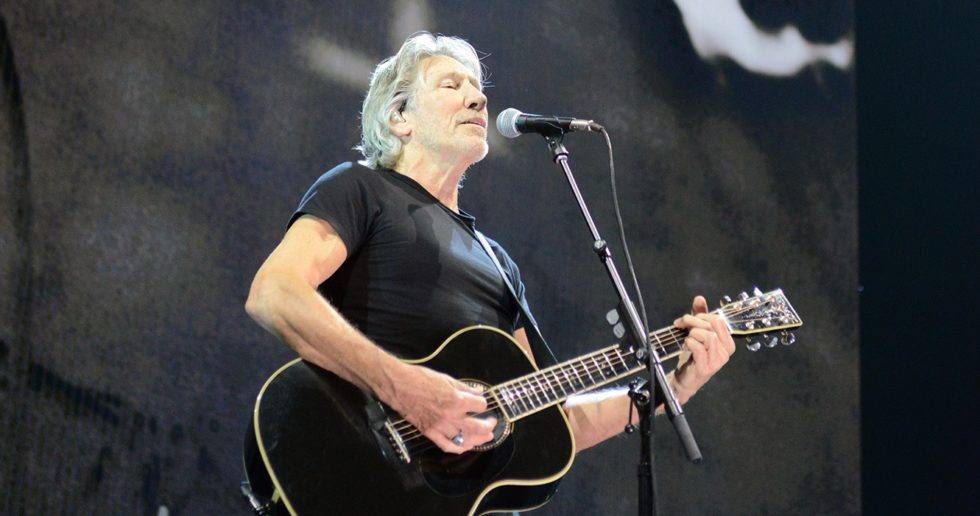

Dr. John, the singer-pianist whose career was dedicated to New Orleans r&b, jazz and boogie, died of a heart attack on June 6. He was 77. The very next day, long before his scheduled funeral, a  second line parade in his honour wove its way through the city’s neighbourhoods. Thousands marched in 100-degree heat, singing old spirituals like “I’ll Fly Away” and r&b classics like “Stand By Me”, all to the beat of parade drums and the accompaniment of trumpets, trombones, saxophones, and tubas. Dr. John’s formal send-off was on June 22, beginning with a public visitation in the morning at a downtown theatre, and followed by a private afternoon memorial service that was broadcast live on local radio. Afterwards, his casket was placed in a long black limousine, and the funeral procession marched to the solemn, slow strains of “Just a Closer Walk With Thee.” A celebratory second line parade followed later that day, with brass bands and thousands of marchers, many in traditional Mardi Gras regalia and some carrying hand-made portraits of the local musician who was born Malcolm (Mac) Rebennack.

second line parade in his honour wove its way through the city’s neighbourhoods. Thousands marched in 100-degree heat, singing old spirituals like “I’ll Fly Away” and r&b classics like “Stand By Me”, all to the beat of parade drums and the accompaniment of trumpets, trombones, saxophones, and tubas. Dr. John’s formal send-off was on June 22, beginning with a public visitation in the morning at a downtown theatre, and followed by a private afternoon memorial service that was broadcast live on local radio. Afterwards, his casket was placed in a long black limousine, and the funeral procession marched to the solemn, slow strains of “Just a Closer Walk With Thee.” A celebratory second line parade followed later that day, with brass bands and thousands of marchers, many in traditional Mardi Gras regalia and some carrying hand-made portraits of the local musician who was born Malcolm (Mac) Rebennack.

In a Rolling Stone interview on Hurricane Katrina’s 10th anniversary he said, “If you can get even one politician to realize the value of a second line, it would make a difference”. It was, therefore, fitting that the passing of an artist who defended such public expressions of elemental human solidarity against their post-Katrina neoliberal detractors should be enthusiastically celebrated with the traditional rites he defended. After Hurricane Katrina (2005) and British Petroleum’s nearby Deepwater Horizon oil spill (2010), Dr. John became a full-fledged activist, performing at benefits, speaking out at against corporate malfeasance, and educating the world about his city’s musical, spiritual, and environmental significance. His family spoke eloquently in the statement that announced his passing: “He created a unique blend of music which carried his hometown, New Orleans, at its heart, as it was always in his heart.”

Dr. John was all about the music of the people.