By Owen Schalk

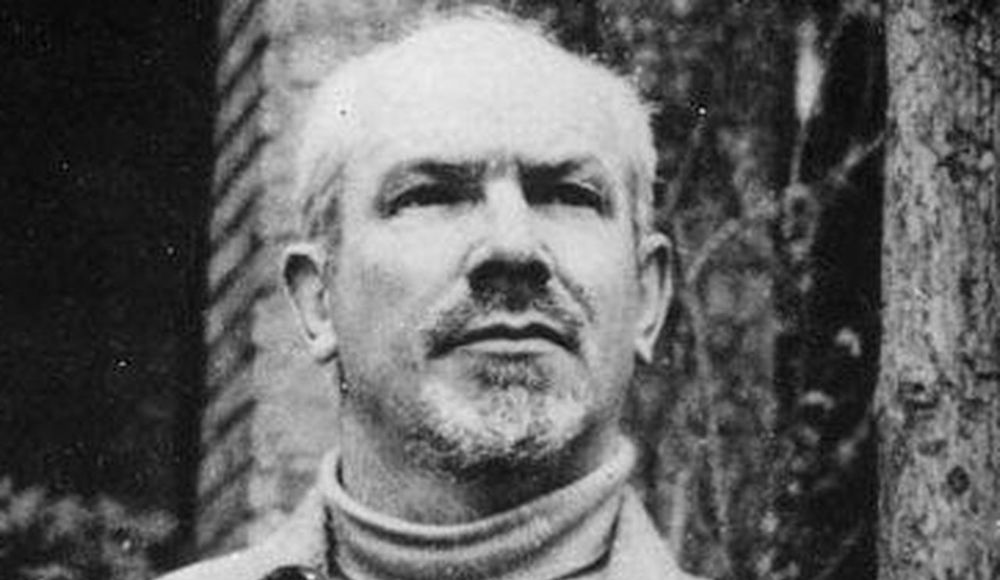

Henry Norman Bethune was an accomplished surgeon, a communist internationalist and a forgotten hero of Canadian history. As a member of the Communist Party of Canada he fought with anti-fascist forces in Spain and later volunteered in the National Revolutionary Army of China during the Second Sino-Japanese War. He was born in Gravenhurst, Ontario on March 4, 1890, and died in the Chinese province of Hebei on November 12, 1939. Despite his enormous courage and deeply felt global solidarity, Bethune has been commemorated quite differently by his native country on the one hand, and the country for which he gave his life on the other.

At the Bethune Memorial Home in Gravenhurst, he is described in the following terms: “Professionally, Bethune gained international recognition as a skilful, dedicated surgeon; socially, he was more unorthodox. He was a complex man who could both antagonize and inspire.” Across Canada he is mostly remembered for his innovations in transfusion medicine, and his politics are excised from the historical record.

The People’s Republic of China, however, commemorates him effusively. There are multiple buildings bearing his name and statues displaying his visage all across the country, and the most illustrious medical honour in China has been dubbed the Norman Bethune Medal.

Bethune was intensely committed to the project of socialized medicine, and he understood that the primary impediment to the equitable distribution of medical care around the world is the capitalist economic system. He described the problem thus: “Medicine, as we are practising it, is a luxury trade…Let us take the profit, the private economic profit, out of medicine and purify our profession of rapacious individualism…Let us say to the people not ‘How much have you got?’ but ‘How best can we serve you?’” He was one of those figures, so rare in history, who lived entirely by the principles he set for himself. Upon his death, Mao Zedong honored him with a eulogy that remains widely known in China. “What kind of spirit is this,” Mao asked, “that makes a foreigner selflessly adopt the cause of the Chinese people’s liberation as his own? It is the spirit of internationalism.”

It is a great historical coincidence that Bethune died one day after November 11, a date on which Canada remembers its own fallen soldiers, while forgetting those they killed in Canada’s name and the reasons they were sent to kill in the first place. In contrast to the restrictive historical outlook reinforced by official Remembrance Day celebrations in the West, Bethune represented, to quote Mao, “the internationalism with which we oppose both narrow nationalism and narrow patriotism.”

Bethune’s medical philosophy is especially relevant in the age of COVID-19, when hundreds of thousands of people are needlessly dying and inadequate medical systems around the world are constantly battered by new waves of infection. It is mainly due to the “private economic profit” of which Bethune wrote, and the deliberate underdevelopment of social infrastructure which the profit motive engenders, that so many people have lost their lives to this pandemic.

It befits Bethune’s internationalist spirit that the most impressive embodiment of the global solidarity by which he lived is not propagated by the Canadian government, but a much smaller country which has put wealthier ones to shame with its medical altruism: the Republic of Cuba. Meanwhile in the US, Canada and other capitalist societies, the internationalist devotion for which Bethune gave his life is sorely absent.

Each November 12, it is important to think of Norman Bethune and to honour his principles by contemplating the loss of all those who have been sacrificed on the altar of private profit.