By Dean Dettloff

“The marketplace, by itself, cannot resolve every problem, however much we are asked to believe this dogma of neoliberal faith. Whatever the challenge, this impoverished and repetitive school of thought always offers the same recipes. Neoliberalism simply reproduces itself by resorting to the magic theories of ‘spillover’ or ‘trickle’—without using the name—as the only solution to societal problems. There is little appreciation of the fact that the alleged ‘spillover’ does not resolve the inequality that gives rise to new forms of violence threatening the fabric of society.”

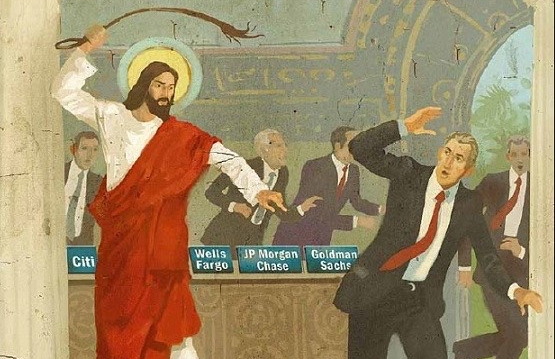

This passage is one of many striking indictments of the present state of global capitalism put forward by Pope Francis in his third encyclical, Fratelli Tutti, or “All Brothers.” Signed on October 3, the document explores “fraternity and social friendship” and is wide-ranging and bold, addressing economics, politics, migration, the COVID-19 pandemic, the death penalty, war and more.

Though obviously instructive for Catholics, Francis addresses his letter to “all people of good will.” Socialists ought to welcome the encyclical as an invitation to dialogue—and there are plenty of points of connection.

In terms of critical analysis, several passages point in a progressive direction. A refrain in the text is Francis’s criticism of an economic system that routinely concentrates wealth and power in the hands of the few at the expense of the many.

For example, he says the response to the financial crisis of 2007-08 only reinforced the ideologies that made such a crisis possible and “increased freedom for the truly powerful, who always find a way to escape unscathed.” The response to the current pandemic, he fears, may very well do the same, if we do not seize the opportunity to reimagine an economy based in solidarity, care and a unified people’s movement.

Pope Francis reaches into the Christian tradition to find resources for building such a movement. Of special interest to socialists is the document’s sections on property. The Catholic Church’s teachings on property have long been a site of struggle within the church. Here the pope says with the authority of his office that while the church defends the right to private property, this right “can only be considered a secondary natural right, derived from the principle of the universal destination of created goods. This has concrete consequences that ought to be reflected in the workings of society. Yet it often happens that secondary rights displace primary and overriding rights, in practice making them irrelevant.”

Francis also calls attention to his observation in his previous encyclical on the environment, Laudato Si’, that “the Christian tradition has never recognized the right to private property as absolute or inviolable, and has stressed the social purpose of all forms of private property.”

While not all Catholics will draw this conclusion, it would be difficult to imagine how capitalism could really function if society were to take the pope’s writing seriously. Private property for some under capitalism is not only an absolute right, for instance, but as Marx and Engels say in the Communist Manifesto, “private property is already done away with for nine-tenths of the population; its existence for the few is solely due to its non-existence in the hands of those nine-tenths.”

The line resonates strikingly with Francis’s assertion that, “In the first Christian centuries, a number of thinkers developed a universal vision in their reflections on the common destination of created goods. This led them to realize that if one person lacks what is necessary to live with dignity, it is because another person is detaining it.”

The church’s defense of private property is so relativized in the encyclical that one wonders what it really amounts to; in any case, it amounts to little in light of the common use of goods. Fratelli Tutti, in other words, elevates and affirms the radical wing of Christian thought on property, one that Marxists can easily find affinities with, even if they will want to say more.

The encyclical is not just a theological treatise. Critical of liberalism and populism alike, Francis makes the case for what he calls a “popular” politics in the interest of the people, which is the primary political category of the document. For Francis, this politics is rooted in “popular movements that unite the unemployed, temporary, and informal workers and many others who do not easily find a place in existing structures.”

These movements are excluded from “monochrome” economic arrangements, says Francis. “Yet those movements manage various forms of popular economy and of community production. What is needed is a model of social, political, and economic participation ‘that can include popular movements and invigorate local, national and international governing structures with that torrent of moral energy that springs from including the excluded in the building of a common destiny,’ while also ensuring that ‘these experiences of solidarity which grow up from below, from the subsoil of the planet—can come together, be more coordinated, keep on meeting one another.’”

While Fratelli Tutti is not a recipe for revolution or a Marxist-Leninist tract, the pope’s call for an integrating “model” is not far from the communist project of building a popular government. Francis’s vision echoes—or one might say is fraternal with—the strategies put forward in the programs for the Communist Party of Canada and the Communist Party USA, which propose to build a coalition of people’s movements and a people’s government. In a world where Catholicism very much remains an animating social force, communists would do well to familiarize themselves with these developments.

True, Fratelli Tutti will not start the revolution. But it could yet help till the soil out of which a dialogical, participatory revolution might emerge, one where the Spectre of Communism and the Holy Ghost might someday, finally, offer a fraternal kiss.

[hr gap=”10″]

Support socialist media!

If you found this article useful, please consider donating to People’s Voice.

We are 100% reader-supported, with no corporate or government funding.