PV Labour Bureau

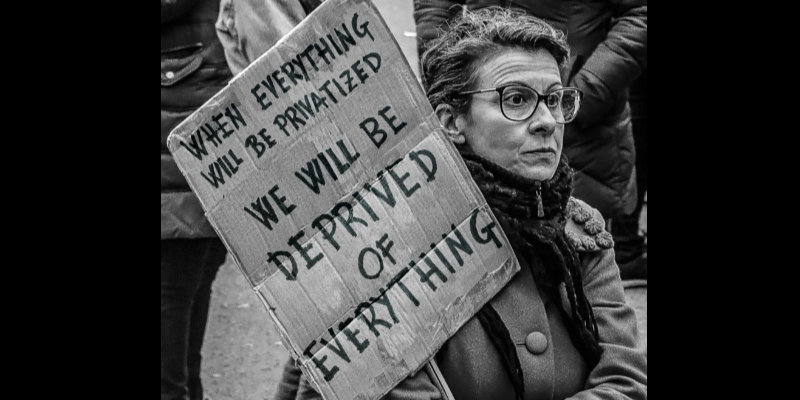

One of the most important outcomes of the COVID pandemic is the widespread call by healthcare workers, community organizations and the public in general, to bring all long-term care (LTC) facilities under public ownership and control. It has been many years since there’s been a mass demand for nationalization like this, and it draws a critical line in the sand in front of the right-wing push for more privatization.

In a recent newsletter, the United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW) warns that right wing governments, corporate think tanks and private healthcare corporations are taking advantage of the pandemic “to promote privatization as the solution to the issues facing the country’s health system.”

The union points to provincial governments which have underfunded the public system while funneling billions to for-profit health providers, pursued P3 (private-public-partnership) models for new hospitals and contracted out a range of health services to for-profit privateers.

This article comes on the heels of a report in the Globe and Mail that the federal government has increased outsourcing of the federal public service by over 40 percent since 2015 – nearly $4 billion. That report quotes Professional Institute of the Public Service of Canada (PIPSC) President Jennifer Carr as saying that the government is creating a “shadow public service” through the outsourcing, one that skirts the rules in terms of transparency and accountability. What the Globe fails to note – unsurprisingly – is that this outsourcing is also a form of mass privatization.

In response to Newfoundland and Labrador’s “The Big Reset” plan (the report of the Premier’s Economic Recovery Team, headed by Moya Greene) in May 2021, UNIFOR warned that the plan’s massive privatization would result in a 4 percent drop in the number of jobs available in the province. The union cited Statistics Canada data about the especially high multiplier effect (jobs created per dollar spent) for government spending on public services, versus private sector spending.

In June 2020, the Canadian Labour Congress (CLC) released For the Public Good, the report of its Task Force on New Forms of Privatization. The document, prepared with extensive involvement of several CLC affiliates, is an excellent analysis of the many forms of privatization, the legislative and funding instruments used to promote privatization, and the range of social and economic effects of such policies.

UFCW is absolutely right. PIPSC is absolutely right. The CLC, Unifor and all the rest are absolutely right.

So, if all these unions are right about the problem of privatization, the question is: “Where is the fight?”

Partly, it’s at the level of individual bargaining disputes at the local level. This is what has happened with municipal waste collection in Toronto over the past decade. In 2011, the city privatized roughly half of the public service, and outsourced more in later years. The union (CUPE) was, and still is committed to maintaining public waste collection, and it scored a partial but important victory for its members when it forced a delay in the city’s plans for another round of privatization. But the union was in a difficult position: the forces of privatization – including governments, corporations and banks – are enormously powerful and individual locals and bargaining units rarely have the resources required to fight them on their own. This challenge is deepened by the loss of members and power that results from outsourcing.

Struggles at the bargaining level – including strikes, work-to-rule and occupations – are absolutely essential. But in addition to local militancy, the fight against privatization needs to be taken to the political level. This is where the labour leadership, particularly at the federation level, really weighs in.

Unfortunately, labour’s current right-wing social democratic leadership has for decades overwhelmingly relied on lobbying for its political work. With cap in hand, they meet with parties which are usually firmly nestled in the back pocket of corporations (Liberal, Conservative) but which occasionally have a relationship with labour that they are prepared to scrap to in order to get/remain elected (NDP). This over-reliance on lobbying is a weak, but enormously expensive strategy and waiting for the NDP to (a) get elected and (b) adopt and implement a left-wing platform is simply a duck and cover approach. These strategies really only guarantee one outcome – the political disengagement of union members.

So, what is the way forward? Labour’s own history shows what it needs to do.

In 1976, when the government of Pierre Trudeau introduced wage controls legislation, labour responded with a historic one-day general strike in which 1 million workers downed their tools. Union activists in the CLC and in Quebec unions like the Confédération des syndicats nationaux worked with social movements to mobilize the grassroots support necessary to build the strike.

In 1983, when BC’s Social Credit government introduced massive cuts to education, health and social programs, and attacked collective bargaining rights by moving to strip unionized workers of seniority rights, the labour movement launched Operation Solidarity. The escalating campaign of rotating strikes and mass protests was made possible because of labour-community alliances that were built up in local communities.

Similarly, in response to the Conservative government of Mike Harris in Ontario in the 1990s, the labour movement worked with social movement allies to build local anti-cuts committees which provided the foundation for escalating action. This grew into the Days of Action campaign, with rotating shutdowns and mass demonstrations in communities across the province.

In 2015, when Ontario’s Liberal government launched the privatization of Hydro One, the province’s electrical utility, unions moved into action. CUPE Ontario had a particularly strong campaign, which mobilized members to coat the province with education, outreach and mobilization. CUPE’s campaign was so effective that it spurred an estimated 180 municipal councils (40 percent of municipalities in Ontario) to pass resolutions opposing the sale.

Through 2019 and into 2020, Ontario teachers and education workers launched an escalating campaign of resistance to government cuts which would lead to increased privatization of education. Their struggle, which united unions with parent and community groups, included public education and outreach, picket line support, lobbying, school “walk-ins” and strike action.

In 2020, when Alberta’s Jason Kenney government announced plans to outsource 11,000 hospital jobs in laundry, patient food services and cleaning, hospital workers held wildcat walkouts across the province.

And, of course, there is the current campaign to nationalize LTC. This is a country-wide effort, led by healthcare workers in every province working with residents, families, health coalitions and community groups. This campaign has included rallies, pickets, petitions, public meetings and lots of organizing.

There are rich lessons to be learned here – when unions trust their members and devote resources to these political campaigns, workers will respond.

In addition to providing cover for privatization, the pandemic is unfortunately often used an as excuse for avoiding mass action. But there are many examples of safe, yet effective mobilizations during the health crisis. On several occasions over the past two years, Indigenous people and their allies have blockaded of highways and railways, often with an effect just as forceful as a major strike. In October, the Ontario Health Coalition held a day of action on long-term care which included rallies and pickets in at least 17 communities across the province, and which received widespread media coverage and public support. And there have been strikes – during the pandemic, there have been nearly 200 work stoppages involving more than 900,000 workers.

The drive to privatization is dangerous and powerful. The only way to oppose it is through unity, organization and a fighting leadership that is committed to mobilizing workers for escalating mass action. The labour leadership – starting at the CLC – needs to commit to this kind of strategy, working with all unions (including the CSN and UNIFOR) and connecting local collective agreement fights with political ones.

There are no shortcuts in the class struggle – if change came through strongly worded press releases, we’d have achieved socialism long ago.

[hr gap=”10″]

Get People’s Voice delivered to your door or inbox!

If you found this article useful, please consider subscribing to People’s Voice.

We are 100% reader-supported, with no corporate or government funding.