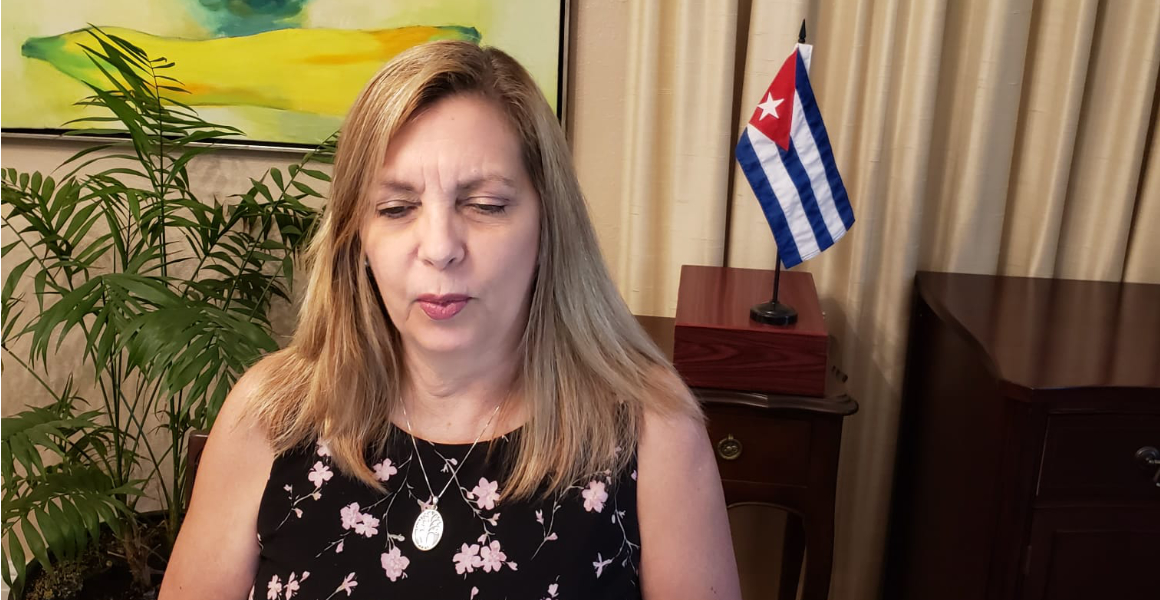

Interview with Cuban Ambassador Josefina Vidal

The importance of the Cuban Revolution cannot be overestimated. For over 60 years, it has stood as a beacon for workers and oppressed people all over the world, and particularly in Latin America. It has survived the six-decades-long US blockade, the overthrow of socialism in the USSR and Eastern Europe, and now, deep global economic crisis brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic. Longtime peace and solidarity activists Miguel Figueroa and Larry Wasslen interviewed Cuban Ambassador to Canada Josefina Vidal, to discuss the current context for the Cuban Revolution. People’s Voice is publishing this interview in three parts, beginning with this look at how Cuba is standing tall in the face of new challenges. Thanks to Bronwyn Cragg for transcribing the recorded interview on which this article is based.

Miguel Figueroa: Could you begin by telling us about the general situation in Cuba, in light of the tightening of the US blockade and the impact of the pandemic?

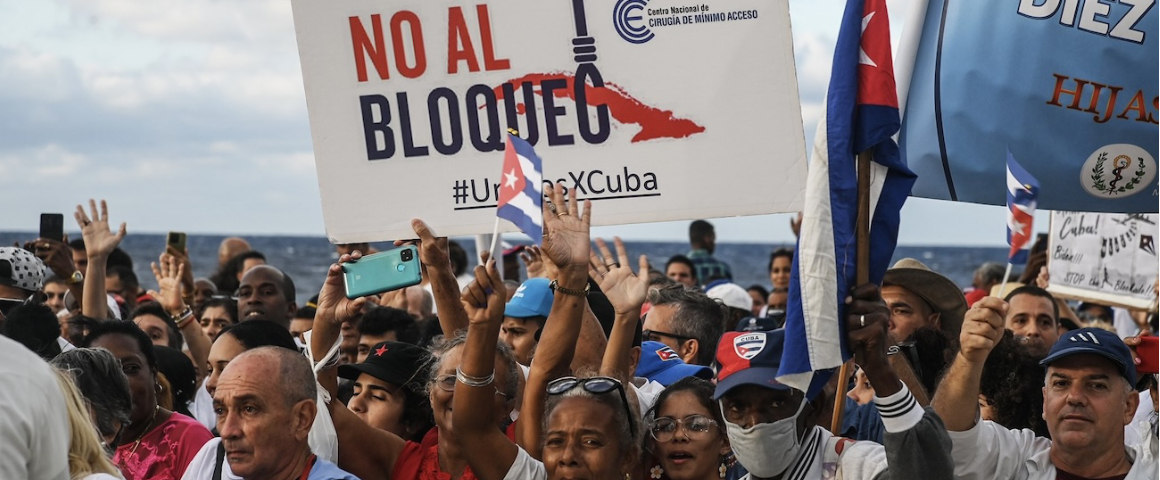

Josefina Vidal: The economic situation now is really difficult. We have been suffering from the combined consequences of a double pandemic: the COVID-19 pandemic as well the pandemic of US sanctions. They call those sanctions but it’s really an economic war against Cuba which has reached unprecedented levels with the measures that the US has adopted mainly in the last two years. But one of the most important negatives that the Cuban economy has had comes from the US blockade. Because of the extraterritorial reach of the US blockade, it affects living conditions of the Cuban people in a very hard way, and it affects Cuba’s relations not only with the United States but with the rest of the world.

At the same time, the economy is still dealing with structural problems and domestic deficiencies that we are trying to solve. Cuba started the process of transformations, huge social and economic transformations, back in 2011. This is a process which is still going on. At the Party Congress there was an analysis on the implementation of all the guidelines that were set up back in 2011 and updated in 2016: 70 percent of the transformations have been implemented, but there is still a big amount — 30 percent — which is pending. And of course, we cannot see the full results yet.

Between 2016 and 2018 the Cuban economy showed a discreet growth of the GDP of 1 percent annually. So, it’s still not what the economy needed in order to make all the progress we need. But in 2019, the GDP contracted by 0.2 percent, due mainly to the US blockade. We started seeing a policy that the US government used to call “maximum pressure” against Cuba, with the goal of suffocating the economy and trying to provoke a social explosion in the country.

Almost every week, there was a new measure implemented by the Trump administration. That was when they decided, for example, to eliminate the “people-to-people” category of travel to Cuba and activate Title 3 of the Helms Burton Act in order to discourage foreign investment in Cuba. This is when they started issuing — or expanding, because that was issued a year before — a list of so-called “restricted Cuban entities.” There are hundreds now and no one in the US is permitted to have dealings with those Cuban entities. Because of the extraterritorial impact and reach, everywhere in the world people are scared and do not want to deal with these Cuban entities, and this is a problem for our foreign exchanges and our foreign trade.

At the end of 2019 they cancelled all possibilities of remittances to Cuba, not only from the United States. Western Union, which is the company that normally runs this operation, decided not to permit remittances being sent from any other third country to Cuba. So, it was impossible to send money, for example, from Canada. That had an impact on the GDP.

In 2020, the contraction of the economy was around 11 percent because we had the double impact of the US blockade and the pandemic. That’s when the economic situation became really difficult. The main purpose of the US unilateral measures was to deprive Cuba of every source of income. You name them: tourism, remittances, persecution of financial transactions. Even the campaign against the medical cooperation program of Cuba with other countries, which in some cases are a source of income because there are, let’s say “medium-developed” countries that are able to pay for the medical services that we provide.

We saw very clearly in 2020 the lower in-flow of income to Cuba, the contraction of Cuban tourism — American travel to Cuba was already suspended, but because of the pandemic we witnessed a shutdown, almost of all tourism to Cuba. We could reopen a little bit at the end of last year but because of the third wave of COVID-19 it is closed again, so no income from tourism. We saw very unstable export markets for Cuban products because of the pandemic and the contraction of the global economy, and we had severe problems with fuel supply. One of the measures of the US government was to persecute and sanction companies and vessels that were transporting oil to Cuba. Domestically, we saw a contraction of production in the country and that had a negative impact on the supply of food and services to the Cuban population. As a result of the pandemic there were several hundred thousand paid [waged] workers and self-employed workers temporarily suspended from work.

Larry Wasslen: But the government didn’t keep its arms folded. It looked for ways to help.

JV: Yes. It started immediately to look for alternatives to mitigate the impact of the situation and, at the same time, to continue the implementation of the goals for the development of the economy. In July last year, the council of ministers approved a specific post-COVID economic-social strategy to boost the economy in the midst of the pandemic, and the main goals of this strategy were greater food security and sovereignty. This is I would say the number one priority for Cuba, how to guarantee food security and sovereignty to depend less on our foreign exchange and our foreign supplies. Cuba annually pays around $2 billion just in food, and some of those products we know that we can produce in Cuba. So now there is a priority to increase the agriculture and food production.

Another goal of this post-COVID strategy is to increase productivity in the main economic sectors. A third goal is how to increase exports and reduce imports. There is an offensive on the part of the government, sitting down with each enterprise to see how much more they can produce in order to export, because export is a much-needed source of income for Cuba.

Another goal is to diversify ways to obtain hard currency in Cuba. Another one was to implement monetary unification, and this is something that we started doing at the beginning of this year. In June, the idea is to finish collecting all the other currency that is still in the hands of the population and after that there will be only one currency, the Cuban Peso. Another goal is to protect and guarantee the basic services to the population in the conditions of the tightening US blockade and the COVID-19 pandemic. It’s like an emergency plan with a very clear idea about which are the main priorities for the economy while the pandemic still lasts.

MF: Is it appropriate to draw parallels between the conditions today and the Special Period in the early and the mid-1990s?

JV: The situation that Cuba is living through now doesn’t have anything to do with the Special Period. There are very big differences. In 1989/1990, when the Special Period was declared after the collapse of the socialist bloc and the Soviet Union, we didn’t have so much foreign investment. Cuba opened more to foreign investment for the first time in the mid-90s – it was designed in order to get out of the Special Period. In the mid-90s, foreign investment was seen as a complement for the development of the Cuban economy. Now, it is seen as an important key element for the development of the economy – we need foreign investment. There is a plan for development until 2030, and we need around $5 billion every year in foreign investment in order to reach the goals that we have set for 2030. So, this is an important change that didn’t exist in 1990; it exists now, so foreign investment is there and is a key component for the development of the Cuban economy.

In 1990, we didn’t have a developed tourism industry. We started developing that in the early 90s and in the mid-90s we expanded. So, that is an enormous difference between the Special Period and now.

In the 90s we were at the beginning of developing the biopharmaceutical sector. At that time, it was not such an important source of income for Cuba. Now it is a very important sector for our economy. You have the example now of the medicines and treatments that we have been developing to treat people with COVID-19 and at the same time the development of five vaccines we have already started using.

So, those are examples of things that did not exist in the 90s and exist today. That’s why, in spite of the fact that we have several problems in our economy — due to the US, the pandemic, and internal/domestic problems that we haven’t been able to fix —we recognized in the Party Congress that the Cuban economy has shown a capacity of resistance in the middle of this very complex and difficult situation. In spite of the shortages of food, people are not hungry. In spite of the shortages of some medical supplies, people are well taken care [of] in Cuba. And in spite of the economic problems, there haven’t been any blackouts.

We had problems in the Special Period with gas supply for the population, and I remember days in which we couldn’t cook in a normal way. That has not happened at all in this year and a half.

So categorically I can say that this is not a new Special Period for Cuba.

Next: Part Two – Canada-Cuba relations

[hr gap=”10″]

Get People’s Voice delivered to your door or inbox!

If you found this article useful, please consider subscribing to People’s Voice.

We are 100% reader-supported, with no corporate or government funding.