COVID-19 has reminded us, brutally, that not only do capital, goods, ideas (useful and nasty) and people flow like wind and water in this world; our mutating viruses do too. Less obviously, the pandemic has put communism back on the table. I use this term deliberately, keeping in mind several notions closely associated with the ‘c-word.’

Healthcare must be freely provided

It should be obvious by now that the single human family’s extreme vulnerability to pathogens requires societies to make healthcare universally and freely available. Chinese authorities have of late trumpeted the virtues of their socialist system, specifically its ability to respond to the Hubei-centred crisis by caring for COVID-19 sufferers at no charge. How could Wuhan have weathered the storm if patients had to pay for treatment? But will Beijing fully learn the relevant lesson? At the height of China’s romance with market forces some twenty years ago, hospitals dealt with limited funding by charging, charging and charging patients. A study led by Professor Wei Fu and published in the British Medical Journal suggests that in 2001, at least 60 percent of health care expenditures in the country were out-of-pocket. Since then, social insurance schemes based on employment and residence have grown to cover virtually the entire Chinese population. But co-payments, deductibles and private plans remain. Healthy China 2030 calls for out-of-pocket payments to drop from around 30 percent of total health spending this year to 25 percent within a decade, but is the projected improvement sufficient?

The official direction established for this millennium is clear. Yet, China’s health spending as a percentage of GDP remains relatively low at just over 5 percent. While this figure is not in itself an indicator of good health outcomes – just note the US’s astronomical figure of 17 percent, a red flag of subsidized profits and waste – it suggests that more could be done, sooner.

Grassroots organization and mobilization

A second lesson of the Chinese COVID experience is that mass mobilization at society’s base is key. It is sometimes said, either in praise or criticism, that the people of this country are ‘obedient,’ but China hasn’t depended solely on either individual assent to coronavirus-containment rules or on enforcement by police. Rather, it has frequently relied on neighbourhood committees, called ju wei hui. These very local bodies exist everywhere in the PRC, serving many functions: basic security units; conduits of information; conflict-resolution forums; seminar and entertainment organizers; mobilizers of care for the elderly; and processors of citizen complaints. While professional security guards are employed to check temperatures at commercial entrances here in Shanghai, many of the monitors covering residential compounds are volunteers mobilized by the committees.

During the lockdown, committees and volunteers in some places went dangerously overboard, with stories emerging of locked front doors, smashed furniture and physical assaults on residents deemed lax in their observance of rules. There were also breakdowns in grocery provision in the viral epicentre. But the system’s overall utility was evident.

This raises the interesting question of whether ju wei hui function as the lowest level of the state or are a tangible example of what that state’s “withering away” might look like, at a basic level of urban life.

Quality housing provided on the basis of need

The populous independent city of Singapore abandoned its light-handed approach to COVID-19 over a month ago. Initially, the government had stressed quarantine for symptomatic individuals and careful tracking of contacts but normal life, including school life, continued. A more thorough lockdown began in April, however, in response to a steep rise in infections. The source of the increase is notable; the disease is reportedly proliferating among Singapore’s roughly 300,000 foreign workers housed in dormitories. In other words, it is almost exclusively South Asian construction and plant workers, living in rooms with 12-20 beds and in facilities where 100 persons might share 5 bathrooms, who are getting ill and infecting others. At a virtual press conference in May, Health Minister Gan Kim Yong told reporters that some 10,000 “community care” beds had been set up to receive the unwell. Meanwhile, individuals who earn a few hundred dollars monthly in one of Asia’s richest jurisdictions remain penned in cramped quarters.

Will the attitude of disdain so long aimed at Singapore’s Indian and Bangladeshi proletariat come back to bite the city state’s more privileged strata? Can COVID-19 teach the rulers and bosses that quality housing for all is in everyone’s longer-term interest?

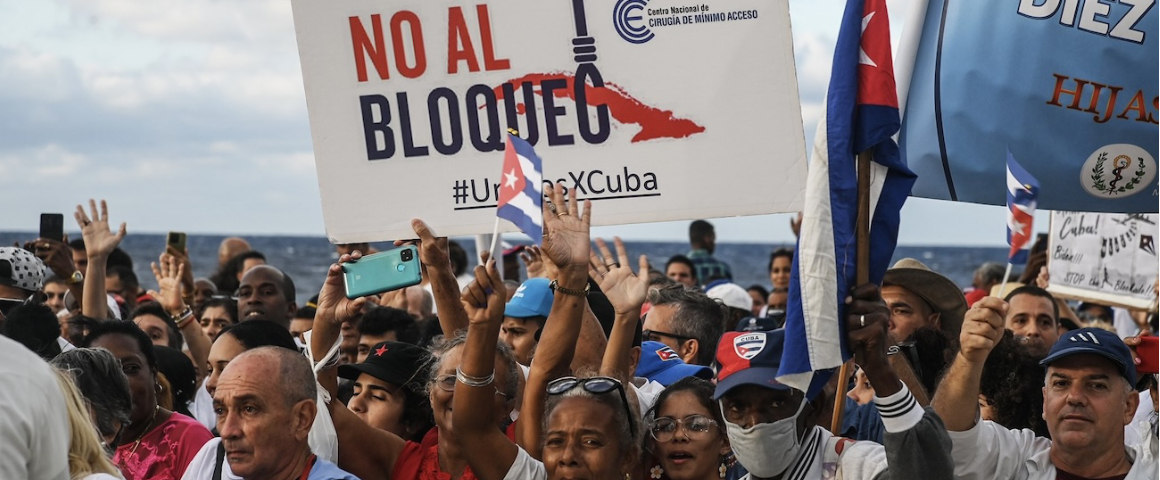

Unity and solidarity

Socially owned and democratically managed enterprises, in a larger context of universal economic guarantees, are the best background upon which to address the return-to-work (and other) questions that arise in pandemic situations. What better way to decide about re-opening workplaces than by asking well-informed workers themselves, provided they aren’t fearful of hunger or homelessness.

Generally, Chinese people do not appear to feel that they were rushed back onto the job. At this writing, there were officially only seven COVID-19 deaths in the country’s largest city, Shanghai, nine in Beijing and eight in huge Guangdong province, next to Hong Kong.

In ravaged Wuhan, meanwhile, people were by and large aching to end a long confinement in their homes. That suffering city will likely provide more and more accounts of the considerable damage done by tense weeks inside small apartments without even the pleasure of a grocery trip.

But contemporary China is not a land of iron-clad social guarantees, at least for most workers, despite its solid record of placing lives over profits during COVID-19. And this brings us to a final consideration: a look at one of the nastier byproducts of coronavirus that did erupt here, the severity of which surely has something to do with shortcomings in the Chinese social system.

Many Chinese workers lost income and employment. Precisely during the crisis period – between the end of February and the close of March – the government invited public discussion on a legislative proposal to slightly ease the terms under which foreigners obtain permanent residence in the People’s Republic. Soon after, a series of disturbing events took place involving the large African community in and around the southern megacity of Guangzhou.

Troubles seem to have begun after the authorities shifted their focus from domestic transmission of coronavirus to importation from abroad. As of March 28, foreigners with temporary, legal permission to reside in China were barred from returning to the country. Several Guangzhou districts saw their status lifted to “medium risk” in early April and became subject to an “intensified screening and monitoring scheme.” This appears to have included a concentration on Africans. Some 4,500 were reportedly tested in the first ten days of the month, with those negative receiving certifications that they were virus free. This was “pro-active screening,” in the words of Tang Xiaoping, director of the municipal health commission. It appears that travel history was not the key criterion for testing or quarantine, but rather real or presumed proximity to an identified viral “hotspot.” By the middle of the month, the city had recorded 119 imported cases, 94 of whom were returning Chinese – all subject to quarantine. But of the 25 foreigners, 19 were reportedly from Africa. As of April 22, Guangdong province, of which Guangzhou is the capital, had recorded 64 confirmed cases involving foreigners; 35 of these were Africans. (Note that at the time of writing, Guangdong’s official case load has dropped to 4).

In early April, a quarantined Nigerian patient bit a worker while attempting to break out of a health facility. A McDonald’s restaurant posted a written notice announcing that it would deny service to African patrons. And numerous Black people reported being suddenly expelled from their rented accommodations by landlords – while others complained that hotels had stopped offering them rooms. Many Africans were suddenly homeless in a city that reportedly hosts some 300,000 individuals from Nigeria, Ghana, Mali and other sub-Saharan states, many of whom purchase manufactured goods in the booming Pearl Delta area for resale in African markets.

In another incident, the Acting Consul General of Nigeria clashed with officials after the latter picked up several of his compatriots with the apparent intention of checking them into quarantine. Nigerian journalist Ikenna Emewu has assembled a detailed summary of events, accessible at www.africachinapresscentre.org.

The municipality and province responded well to criticism. Residents and businesses have been sharply reminded that individuals must not be denied the access to hotels, rental facilities, or services like restaurants because of their nationality, colour or gender. This was affirmed in a mid-April proclamation by the General Office of Guangzhou Command Centre for COVID-19 Control and Prevention.

For his part, Luo Jun, Deputy Director General of the Foreign Affairs Office of Guangdong province, stated that acts of discrimination against Africans would lead to sanctions, and noted that penalties had been recommended for those in charge of the McDonald’s branch cited earlier. Racist acts were the result of individual behaviour and not government policy, he insisted.

Which returns us to the discussion of permanent residency for foreigners mentioned previously. In the midst of COVID-19-induced tension, China’s huge Sina Weibo social media platform was flooded with appalling invective from “netizens,” much of it directed against Africans. What was absurd – as well as objectionable – about their xenophobic rhetoric was that it was launched against a timid reform designed solely to accommodate some very privileged professionals, so-called high-grade “foreign talent.” Few African traders, or European teachers for that matter, are going to take advantage of the new rules governing the rarely issued Chinese “green card,” with the possible exception of those married to citizens. But a shocking number of tweeters were certain that China would be culturally diluted, its civilization rendered unrecognizable, and social unrest unleashed if the law as outlined were passed.

As Ugandan journalist Mubarak Mugabo wrote, “…individual citizens should be educated on how harmful their biases [can] be…”

Another take on the matter, from an extensively schooled, well-travelled Shanghainese professional who prefers not to be identified, placed less stress on the ‘education’ of bigoted citizens. Commenting on the internet’s hostile reaction to eased permanent residency proposals, this individual observed, “Most people reacted on the basis of their own interest…Poverty is still the main issue in most areas. In China, competition is everywhere. How can you expect people to welcome more competition? Even among Chinese citizens, there are conflicts between local residents and new arrivals. People are more selfish when survival is hard.”

And “Guangzhou is known for its African population. Many [members of the community] are said to be illegal.” It is thought that “the crime rate is high there partly due to this fact. People from other cities don’t want that to happen to their cities.”

Hm. Where haven’t we heard all this before?

[hr gap=”10″]

Support socialist media!

If you found this article useful, please consider donating to People’s Voice.

We are 100% reader-supported, with no corporate or government funding.