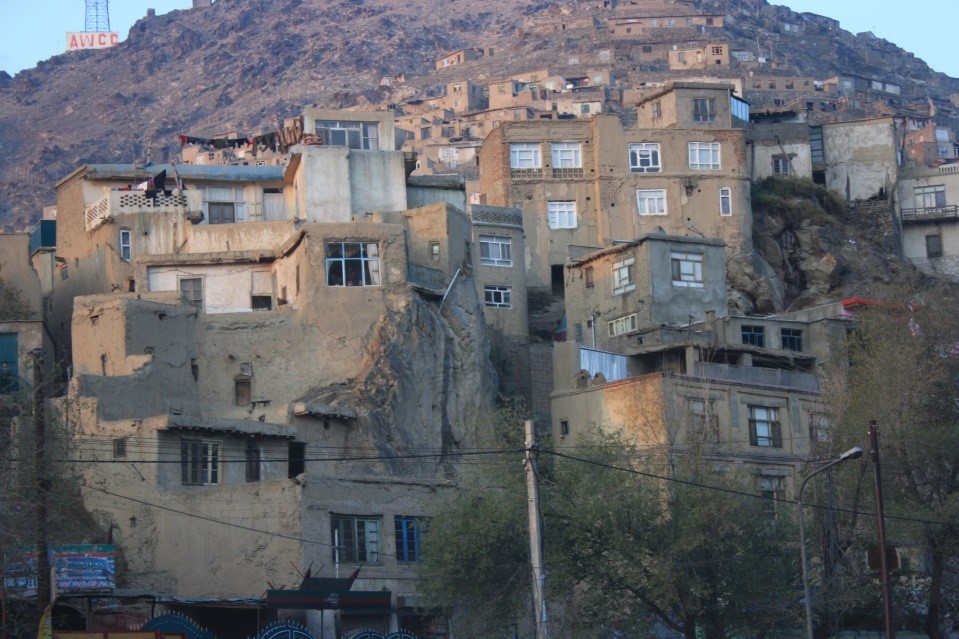

A dark cloud of vengeance over Kabul

Special to PV, by Lawang Diyar

On February 29, a historic event took place in the Qatari capital of Doha, when formerly blocklisted Taliban representatives signed a historic peace deal with top US diplomat Zalmai Khalilzad. Khalilzad, by the way, is also a native Afghan.

It represents the first official and fruitful gathering of the two rivals since the 2001 invasion of Afghanistan by the United States and the military mission of “Operation Enduring Freedom.”

A historic playback provides some light on the background of the current political stalemate in Afghanistan:

The Taliban regime (1996-2001), originally backed by the US and managed by the Pakistan Intelligence Service, was toppled after the 9/11 terrorist attack on New York’s Twin Towers, which killed over 3000 people. The ouster of the Taliban in 2001 introduced new political players in Afghanistan, all of them having ties with the United States during the war against the Soviet-backed Afghan leftist government.

One-time jihadi leaders, who had been on the run from Taliban repression, returned to the political corridors and afterwards enjoyed US financial and political support. The complex political climate with multiple players on the ground worked well until the US presence in Afghanistan became noticeable in every aspect of life. Various jihadi factions and US-educated technocrats shared the political pie for almost 20 years. During this period, democratic leftist forces were unofficially banned from participating in political discourse and from organizing. Many were laid off, sent to retirement or banned from government positions. Some survived the political “cleansing” by serving the new political elites. A few thousand of them were massacred earlier in the 1990s after the takeover of power by the jihadi warlords.

With over 18 years on foreign soil, Afghanistan is the longest war the US ever fought. It is estimated to have cost up to $1 trillion. The US also suffered major casualties with 2440 military and 1720 contractor deaths and 20,320 wounded soldiers and contractors. The psychological toll of the Afghan war is even more significant. However, the US invasion did not amount to significant Afghan development, state-building and, most importantly, peace. Today, the country’s political structures are shaking, and political stability is far from normal. Security is dire and the number of deaths due to war activities is between 100 to 150 per day.

Lack of progress in the restoration of peace, the continuation of the Taliban military campaign and the poor performance of Afghanistan in the economic and human rights stages made this country a losing battle for the United States.

During the past two decades, a Western neoliberal democracy was introduced in Afghanistan. The elections in Afghanistan during this time period were not based on social and economic issues; instead, their root was the creation of momentum and campaign rhetoric. Soon after each election, the momentum evaporated, but the problems stayed. Massive embezzlement of public funds, corruption and nepotism by the US allies is the true face of Afghan democracy over the past two decades. The Afghan elections’ winners and losers would always get rewarded by the US and its international allies, to save the face of Afghan democracy. The Taliban, on the other side, continued fighting the US in the hope they would be brought to the negotiation table with the help of Pakistan and their friends in the Afghan government.

After almost two decades of experiments, the United States decided to enter into negotiations with its former client force and then rival. The biggest supporter of the Taliban, the Pakistani government, acted as the negotiations’ broker in the hope of getting rewarded. Both the United States and the Taliban started the negotiations with big hopes and expectations.

The US Special Representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan, Zalmai Khalilzad, was appointed to lead the negotiations, which were held in Qatar’s capital city of Doha. Behind the back of the American workers and taxpayers, millions of dollars were allocated for the talks, which lasted 18 months. A prepayment was made to cover the Taliban free movement and business class treatment, wherever they went. Although the official figures approved by the US Congress in February 2020 are $15 million, unidentified sources suggest that up to $50 million has been spent since September 2018 to support the Taliban’s air travel, per diem, lodging and negotiation expenses.

The US-Taliban agreement was signed without the participation of the Afghan government. While it is itself sponsored and supported by the US, the government was blocked from negotiations under the pretext of later Intra-Afghan Dialogue. An important part of the agreement is that the United States committed to releasing 5000 Taliban prisoners – prisoners who are in the Afghan government’s custody. This part of the agreement reveals an interesting twist – either the US is under the assumption that it can influence the Afghan judiciary system and release the prisoners at any time, or they believe that their leverage with the Afghan government is so high that with one email or phone call the prisoners will be freed. This did not happen.

The agreement also indicates the US desire to pull out their troops in 14 months, subject to the implementation of all terms. In one very controversial term, it is agreed that the Taliban will fight ISIS, Al Qaeda and other anti-US groups. Despite a functioning government in Kabul and an army that was built with the same American funds, the agreement places the Taliban in charge of combating terrorism.

Clearly, the US wants to leave this troubled country, even if it means abandoning the results of its expensive 18-year-old war. However, the United States is also hoping to maintain a political and even some military presence in Afghanistan, in order to remain a significant player with less financial commitment attached to this presence.

The exclusion of the current Afghan government from the peace process was a mistake that backfired after the agreement was signed. The prisoners were not freed as agreed by the deadline and the Intra-Afghan Dialogue did not start. Instead, heavy fighting erupted in the north of the country with many casualties from the government and Taliban. On both sides, more Afghans are being killed every day.

The National Unity Government (NUG) of Ashraf Ghani has been weak since it was imposed on Afghanistan by the US in 2014, in what was a classic temporary solution to a deep political crisis in the country. The initiation of unity and ethnic quota-based governments has a long but tragic history – Lebanon, Iraq, Libya and other countries all have negative memories of such governments. During the past five years, Afghanistan has achieved very little due to the constant clashes between the various rivals in the NUG. In 2019 Ghani came up with a more pragmatic agenda to fight corruption, downsize the warlords and distance himself from the US on some key issues. His developmental agenda and plea to fight corruption and warlordism has dismayed many, including the supporters of the former president Hamid Karzai, who flourished during the US heavy presence in Afghanistan.

The 2019 presidential election, and the subsequent 5-month delay in announcing the results, produced two rival camps who simultaneously declared themselves victorious. Both Dr. Ashraf Ghani and Dr. Abdullah consider themselves the President of Afghanistan. The historical low voting turnout diluted the elections’ legitimacy, and the overall situation has created better circumstances for the US to leverage its agendas and impose its own solutions on the country.

One of those solutions involved making the Taliban part of the political elite and end the endless war. This could also serve another purpose, and that is as a card for Donald Trump to use during the 2020 US presidential election. With the deal signed, it is now up to the US to determine how to implement the articles of the agreement. The Taliban have been elevated from blocklisted guerrillas to a major force, received in major diplomatic events and financially supported by US funds. Keeping in mind the latest developments on the ground, there are two possible scenarios in the post-agreement political scene in Afghanistan, subject to its successful implementation.

The first possibility is that the Taliban become a key part of Afghan politics. Their leaders will receive major financial and political incentives, the US will keep its military presence in some way or shape, and the Taliban will keep their eyes closed that presence. This same scenario played out for Jihadi leader Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, who fought the presence of the Soviets and the Americans. After the signing of a lucrative peace deal, Mr. Hekmatyar is now residing in Kabul and is collecting big government pay-cheques that are funded by the US, while closing his eyes to the American military presence.

The second possibility is that the Taliban enter the Afghan political regime as the only force that is supported by other Jihadi warlords, who used to have close ties with the United States. These warlords have had in the past, several agreements and secret relations with the Taliban. In this case, the Taliban will be the main stakeholder to the United States in Afghanistan; the Jihadi warlords will act as their subcontractors. Most Afghan ex-pat bureaucrats will be out of power, and the role of Pakistan will be propped up as the major US ally responsible for Afghanistan.

The COVID-19 pandemic has added more problems to an already profound Afghan socio-political and economic tragedy. With the combined crisis, it clearly will not be easy or quick for the Taliban to be part of the state elite. The political talks and agreements have given the Taliban more confidence; they are now not willing to be part of a government and are leaning towards the second scenario. They want to be the government in its entirety.

In both cases, a major political shift is anticipated. The Taliban’s job as a fighting force will come to an end, and another force will be introduced to take their position and keep the Afghan war alive. This political game by the US will reduce its financial burden, but also maintain its presence in Afghanistan and introduce a much harsher player to the political scene.

There are significant lessons to be drawn from this year’s political blunders. US involvement in Afghanistan introduced an elite class to the country, which is considered the driver of change and is the point of concentration of capital. Most aid money, grant funds and opportunities are in the hands of a few who run the economy and, therefore, the politics. The US and EU involvement did not amount to development in the peripheries. The annual GDP of the Afghan non-urban countryside is still under $300 annually. The illicit drug economy is many times larger than the licit economy. The international community financial support could bring a major change in Afghanistan if the aid fund were not in the hands of US-allied Jihadi warlords and elites.

The introduction of another force to the Afghan political chess plate will likely complicate the situation for Afghans, while it may reduce the cost of war for the United States.

The issues of human rights abuses by the Taliban and Jihadi warlords, including the mistreatment of women, will fall off the radar, and the Western media will project a positive and more humane picture of the Taliban. The Afghan people will once again become entrapped by medieval forces, this time underpinned by the US-Taliban agreement.

While many around the world applaud the recent developments, the Afghan people see what is coming. It is a dark cloud of vengeance.

Afghans have always relied on themselves to find solutions for their problems; this time will be no different.

Lawang Diyar is the pseudonym for a scholar from Kabul, Afghanistan.

[hr gap=”10″]

Support socialist media!

If you found this article useful, please consider donating to People’s Voice.

We are 100% reader-supported, with no corporate or government funding.