A winter of labour discontent is beginning to emerge on the west coast. Transit workers in Metro Vancouver are in the headlines, and a wider series of struggles is rippling through British Columbia, as economic woes and spending restraints hit the working class from different directions.

The shutdown of many forestry operations across the interior has left thousands jobless and threatens the viability of small towns, and a strike by USW members at Western Forest Products mills on Vancouver Island is now into its fourth month.

In Metro Vancouver, thousands of hotel workers have achieved improved collective bargaining gains this fall, with the Rosewood Hotel local of Unite-HERE the last to reach a settlement in mid-November.

Potentially the biggest dispute pits the BC Federation of Teachers against the BC Public School Employers, which bargains on behalf of the province. Negotiations are stalled, as the NDP government limits annual public sector pay increases to just 2 percent, even as many BC teachers leave for other provinces where salaries are higher and housing costs lower. Red-shirted BCTF members and education activists protested at the annual NDP convention in Victoria on November 23, angry that the government they helped to elect refuses to budge on pay rates and classroom conditions.

But the escalating job actions by transit workers are the biggest news. A three-day withdrawal of Metro Vancouver bus service is planned for November 27, 28 and 29. Unifor Locals 111 and 2200, which represent 5,000 bus drivers, mechanics and Sea Bus workers, resumed bargaining with the Coast Mountain Bus Company on Nov. 26, after Unifor President Jerry Dias arrived in Vancouver to join last minute negotiations.

The Unifor locals bargain jointly with CMBC, under one contract which expired on March 31. When negotiations broke down in mid-October, the union members gave their negotiating committee a 99.3% strike mandate. CMBC eventually returned to bargaining but put forward no substantial changes to their offer and left the table again. The union responded with 72-hour strike notice effective November 1.

The action began with drivers refusing to wear their uniforms, and a ban on overtime for maintenance staff and Sea Bus workers. This resulted in a 10% reduction in service and the cancellation of multiple Sea Bus sailings to North Vancouver. The impact on the public was minimal, but very visible, and the restraint shown by the union was greatly appreciated by transit users. CMBC had no response to this action, so the union decided to escalate the job action to a three-day withdrawal of service. What happens next is squarely up to CMBC, but clearly the transit workers are determined to win a fair settlement.

The main issues are parity in wages and working conditions with other transit systems in Canada, and with Metro Vancouver Sky Train workers, who are in another union and are also bargaining at this time with a different employer. CMBC mechanics and maintenance staff are far behind the wages of their Sky Train counterparts for doing identical work.

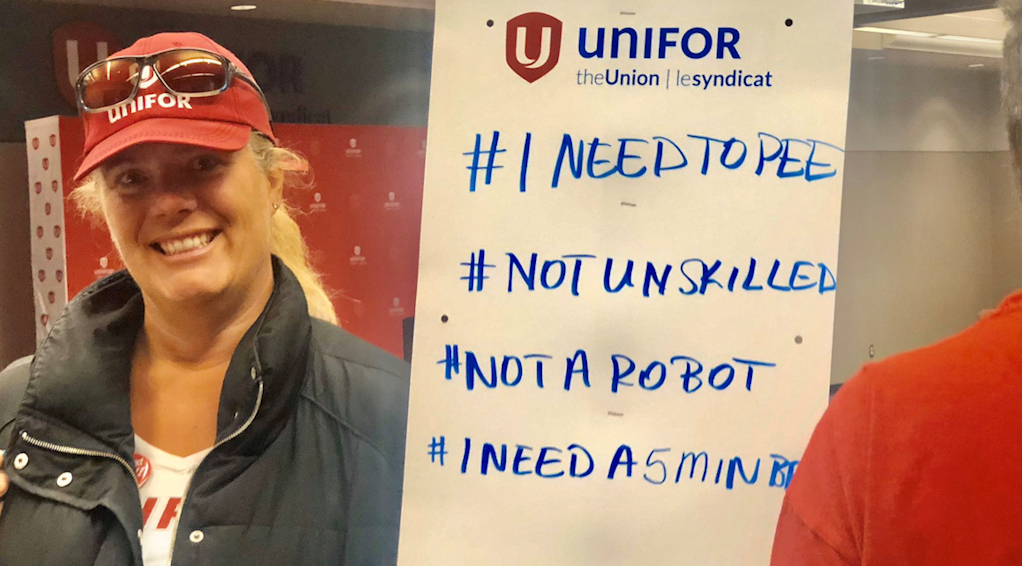

Possibly most important for the bus drivers is the issue of working conditions. Due to the nature of their jobs, transit drivers are not guaranteed scheduled breaks for coffee and lunch, or to take care of personal needs during the day. They are required to fit these things in between trips during their shifts. For years, proper scheduling of running times allowed operators enough time to satisfy their nutritional and bodily needs between runs. In recent years, the company has ruthlessly squeezed running times and breaks, so that many drivers do not get more than three or four minutes between runs. If they are running late, which is usually the case, they must choose between taking a washroom break or starting their next run already behind time.

The impacts for operators have been massive. Assaults are rising because of passenger anger and frustration, and drivers increasingly experience stress, anxiety and exhaustion, which is putting public safety at risk. Transit operators have had enough and are willing to do what it takes to settle this dispute in favour of improving their working conditions and wages.

The complex web of transit operations and unions in Metro Vancouver makes this set of negotiations difficult for the public to understand. CMBC is a wholly owned operating subsidiary of Translink, which is the public body that oversees the system. Yet Translink is not accountable to the public. Translink CEO Kevin Desmond, who is paid $517,000 annually, is notorious among the workforce for screwing up Seattle’s transit system before coming to his current position. Mike McDaniel, who came to CMBC from the PNE, also has a shady past in labour relations, and gets paid $372,000. Both were recently given 25% increases, justified by the claim that they need to be competitive with other transit bosses, but Desmond and McDaniel deny workers the same consideration.

The union negotiating team has asked for parity with other transit workers, using Toronto as the example. When McDaniel said that it would be hard to justify giving parity to bus drivers, Unifor members were very insulted, and he has since backed away from that comment.

A compounding factor in this labour struggle is that since Unifor remains outside the CLC, there has been little sign of public support from the Vancouver and District Labour Council or the BC Federation of Labour. While Unifor fully expects CLC affiliates to respect its picket lines, the situation highlights the lack of unity among different sections of the labour movement.

CMBC workers are represented by three unions, Unifor, COPE (office and technical staff) and CUPE (mid-level road supervisory employees). The Sky Train workers, mainly represented by CUPE, are pushing ahead with arbitration, creating the potential to get the public asking why CMBC employees didn’t do the same. If Unifor and CUPE had official relations, it would have been possible to develop a common strategy, to hold off on settling until both are done, or at least to coordinate actions so as not to negatively impact the others’ negotiations.

The lack of unity emphasizes that the Unifor leadership’s decision to remove itself from the house of labour was not in the overall interests of the working class.

BC Labour Committee, CPC