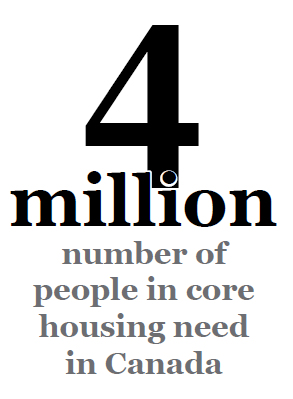

According to the 2016 Census, 1.7 million households across Canada – 13% of the total – live in what the government refers to as “core housing need.” This term is applied to situations in which people spend more than 30% of household income on housing that is inadequate (crowded or in need of major repair). With an average household size of about 2.4, this means that over 4 million people cannot afford adequate housing. Notably, figures for core housing need do not include homeless people, who have been estimated to number as many as 300,000 in Canada.

By far, the highest level of core housing need is in Nunavut, with over 36% of the territorial population. The proportion also jumps significantly in urban centres – in Toronto, for example, nearly 20% of the population is living in core housing need.

By far, the highest level of core housing need is in Nunavut, with over 36% of the territorial population. The proportion also jumps significantly in urban centres – in Toronto, for example, nearly 20% of the population is living in core housing need.

So, what’s behind this housing crisis? There are two key factors: supply of affordable units and soaring costs.

To be sure, there is a lot of housing being built in Canada. Information from Statistics Canada shows that total investment in building residential housing last year was over $121 billion. This figure increased in each of the previous five years and is a whopping 26% higher than in 2013. In virtually all areas of the country, it seems, residential housing is being built and rebuilt. The problem is that it is too expensive.

According to Industry Canada statistics from 2017, the profit margin for residential housing construction corporations is 33%. Furthermore, 80% of housing corporations make a profit – residential housing is a very profitable and reliable place for capital to concentrate. Based on that date, it is reasonable to assume that roughly $40 billion in corporate profits were made off residential housing construction in 2018 alone. This is just the profit from building – it doesn’t include money made by landowners through rent or resale.

With all this profit built in, it’s no wonder that housing costs have skyrocketed in virtually all areas of the country. In January, the average rent for a one-bedroom apartment in Toronto was $2300 per month. In Vancouver, it was just over $2100, in Montreal it was $1500 and in Ottawa it was $1300. These numbers are increasing and increasing fast.

The average cost of a home, across Canada, is around $500,000. A purchase on this scale involves a mortgage cost of nearly $2000 monthly and requires an estimated $110,000 annual income, more than double the average household income of $47,000. Here, again, the prices increase dramatically in urban centres – the average cost of a home in Toronto is around $800,000 and over $1,000,000 in Vancouver.

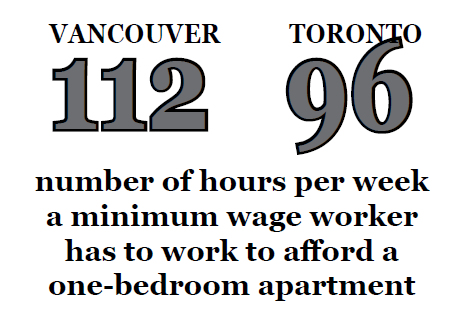

A study published in July by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA) examined the 36 metropolitan areas in Canada and found that 31 of them “have no neighbourhoods where a two-bedroom apartment – the most common type – is affordable for a minimum wage worker.” In Vancouver and Toronto, there is not a single neighbourhood in which a full-time minimum wage worker could afford an apartment without spending more than 30% of their earnings. The CCPA calculated that “in Vancouver and the Greater Toronto Area, a minimum wage worker would have to work 112 or 96 hours a week, respectively, to afford a two-bedroom apartment—84 or 79 hours a week, respectively, for an average one bedroom.”

During this election, and for a long time prior, there has been a lot of talk about “affordable” housing. But there’s very little discussion of what exactly is meant by affordable. In most cases, politicians and industry representatives use the term to mean housing costs that are at or below market. But this is a moving target, and one that is rising at a much faster rate than people’s incomes. In Ontario, for example, housing costs increased by 24% between 2016 and 2017, a trend that is present in other areas of the country.

The market-based notion of affordability is the one that is used by all the mainstream political parties – Conservatives, Liberals, NDP and Greens. However, this definition is a false one as it deliberately avoids relating the cost of housing to the income of the person buying it – surely any useful concept of affordability needs to take this relationship into account.

How to resolve this?

Clearly, a lot depends on taking profit out of housing. For the past 3 decades, governments at the federal and provincial levels were happy to get out of the housing industry and rely, with different amounts of coaxing and incentives, on the private sector to provide affordable housing. And for 3 decades, all people have seen is dwindling supply, increasing costs and huge private profits, leading right into the current crisis.

Liz Rowley, leader of the Communist Party of Canada, has been campaigning for a federal housing program that is based on public ownership and delivery of social housing. “If housing is, indeed, a human right then it must be treated as a public utility and provided on the basis of need. Taking profit out of the mix allows for costs to decrease to a truly affordable level.”

That brings back the issue of affordability – if it is not pinned to market prices, then what is the benchmark? For the government it’s 30% of household income, the financial cutoff for core housing need. For Rowley and the Communist Party, that’s still too high. “We demand rent rollbacks and strong rent control legislation so that nobody has to pay more than 20% of their income on housing.”

This means a huge increase in Rent-Geared-to-Income (RGI) housing units, which place the specific needs and condition of each individual household above other considerations.

There are specific groups whose housing needs are especially dire and require special attention. Indigenous communities often have desperate shortages and the housing that exists is often in very poor condition. The Assembly of First Nations developed the First Nations National Housing and Infrastructure Strategy to confront the housing crisis experienced by First Nations people living on and off reserve. The strategy document clearly connects housing with Indigenous sovereignty: “First Nations care and control of housing and infrastructure is the guiding principle.”

Attention also needs to be paid, urgently, to building safe and accessible emergency shelters and transitional housing. Too often, politicians have taken the view that it is better to build homes for homeless people than to build emergency shelters. In doing so, they sacrifice the lives of hundreds of homeless people who will die on the streets while they wait for housing to be built. The reason shelters are constantly pushed off the priority list is simple – they don’t make money, whereas housing does.

Business journalists like to write about the “housing bubble” and speculate how investors can shield themselves – or even benefit – when it bursts. But they ignore the fact that for millions, the bubble holds necessities more basic than investments, and it has already burst.

The basic needs of all human beings are food, clothing and shelter. The degree to which housing has been commodified in Canada, the amount of profit that is extracted out of this basic human need, is a clear indictment of capitalism. We are well past the point of realizing that the private sector cannot provide housing; there is an unquestioning need for decisive government intervention.

The fight for socialized housing and legislated rent rollbacks brings the working class into direct conflict with huge and powerful corporations, who will not easily yield their cash cow. It is a long-term struggle that is already being fought in communities across Canada, but that needs coordination and structure. This is a demand that needs to be taken up by the entire labour movement, during elections and beyond.

[Header photo credit: Alan Pike]