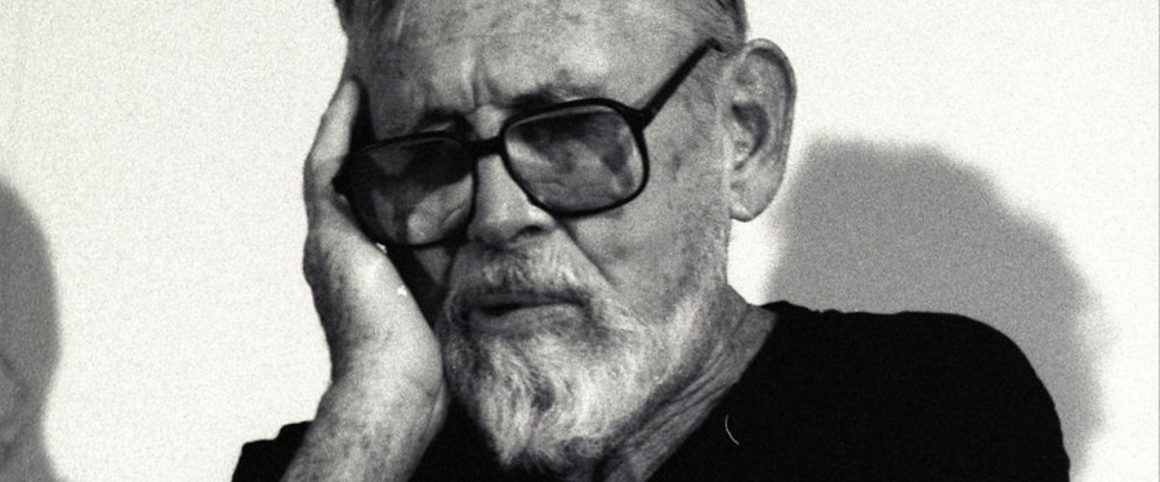

Pauline Julien, Intimate and Political

Singer, actress, songwriter, and outspoken advocate of Québec independence, Pauline Julien (1928-1998), is the subject of a new National Film Board documentary by director Pascale Ferland. Pauline Julien, Intimate and Political is a portrait of an artist who attracted a large following in the music halls and cabarets of Paris in the fifties with her dramatic performances of love songs in the nouvelle chanson style. In 1961, after a decade in France, Julien returned to Montréal, where she began to interpret songs by contemporary Québec composers like Raymond Lévesque and Gilles Vigneault. Like those artists, Julien was a separatist. Given her popularity, she soon became one of the most visible advocates of independence. Julien’s political statements often made headline news. In 1964, she declined an invitation to sing before the Queen. A few years later she sang at a benefit for imprisoned members of the FLQ. During the October Crisis of 1970, Julien and her life companion, the poet Gérald Godin, were arrested and held without charge for eight days. When the separatist Parti Québécois, led by René Lévesque, swept into power in 1976, Godin was elected to the National Assembly, defeating incumbent premier Robert Bourassa in his own riding. Godin served in Lévesque’s cabinet when the Charter of the French Language (Bill 101) was passed in 1977. It was the high-tide of the independence movement. Godin was to die of cancer in 1994, and Julien, diagnosed with a debilitating brain disease, took her own life in 1998. Looking back, one might see their deaths as symbolizing the end of an era. Last month, the Coalition Avenir Quebéc came to power. Premier Francois Legault (a conservative former PQ cabinet member) declares that separatism is dead. Meanwhile, the nominally social-democratic Parti Québécois languishes in third place with 17% of the popular vote. Bill 101 is still in force, with each subsequent amendment generating fresh controversy. Separatism may be on the margins of contemporary political discourse, but Pauline Julien, Intimate and Political, portrays a vibrant artist, for whom the separatist cause was identified with cultural revolution and feminism as well as independence. Pauline Julien’s long career spanned two continents, 23 albums, and hundreds of songs (many her own). To her fans she was “la passionara” – the soul of the movement. For info: www.nfb.ca/film/pauline-julien-intimate-and-political.

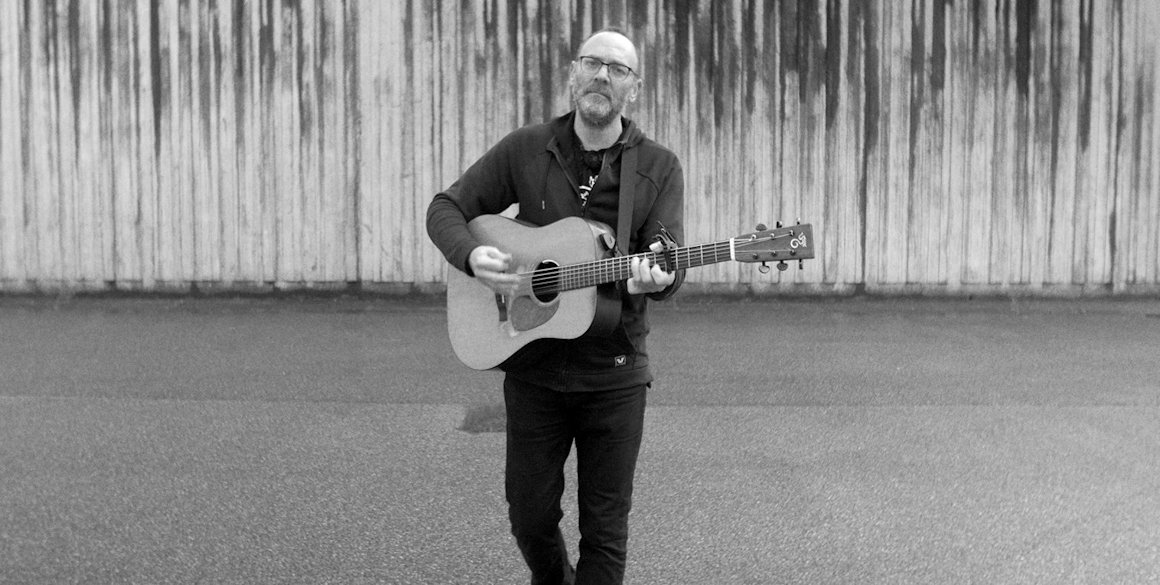

Roots, Radicals and Rockers

“Roots, Radicals and Rockers: How Skiffle Changed the World” is a new book by the popular English socialist musician Billy Bragg. It’s an engaging history of a grassroots do-it-yourself cultural revolution in 1950’s Britain whose influence is still being felt today. Bragg established himself in the early eighties as a post-punk solo artist who accompanied his original songs with highly distorted electric guitar. He views the skiffle phenomenon in the fifties as akin to the punk rock uprising against corporate rock in the seventies. So what was skiffle? In African American parlance it was a rent party. But for British youth in the fifties, skiffle signified a genre of American music. It emerged from the “trad jazz” movement in the early fifties, whose leading exponent was trumpeter-guitarist Ken Colyer. His pilgrimage to New Orleans, and his subsequent association with the “founders” of jazz, placed Colyer at the epicenter of a “back to basics” movement – one that rejected the swing-oriented pop music still in style in Britain. In bands like Colyer’s, it became the rule to have a “breakdown set” in the middle of a show, featuring a small combo of musicians performing the folk-blues of African American artists like Leadbelly, and accompanying themselves on acoustic guitar, banjo, tea-chest bass, and washboard. In 1954, singer, guitarist and banjo player Lonnie Donegan, a member of the Chris Barber Jazz Band, had a million-selling skiffle hit with a Leadbelly-influenced recording of “Rock Island Line”. In Donegan’s wake, skiffle became a mass phenomenon. Guitar sales in Britain skyrocketed from an annual average of 5,000 to 250,000, and skiffle bands popped up everywhere. One such band, The Quarrymen, famously became The Beatles. Indeed, most of the prominent British bands of the sixties had roots in skiffle (e.g. David Bowie, Van Morrison, The Who, Led Zepplin). Bragg acknowledges the important role of left-wingers in the skiffle movement, including members of the Communist Party of Great Britain. YCL member Hylda Sims, the daughter of a founding member of the CPGB, and John Hasted, a communist physics professor, were significant performers as well as organizers of networks of skiffle coffee houses and clubs. So too was the well-known folksinger and CPGB member Ewan MacColl. The presence of some of the best-known skiffle and trad jazz bands in the anti-nuclear and anti-racist struggles in Britain in the late fifties testifies to the success of their efforts. For more info: www.billybragg.co.uk