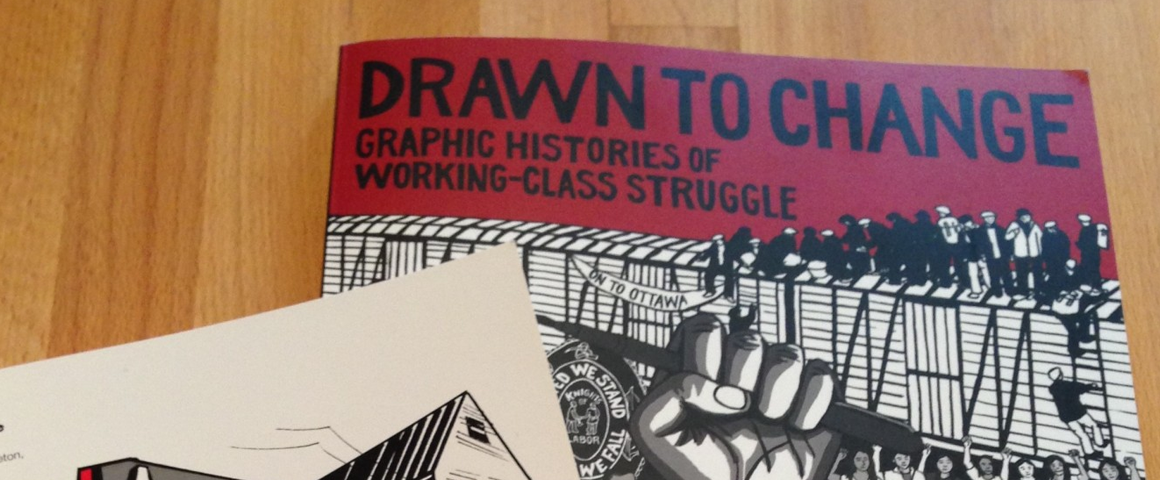

Drawn To Change, published in Toronto by Between the Lines, 2016. Graphic novel review by Michael Zaharuk

“Changes and progress very rarely are gifts from above. They come out of struggles from below.” – Noam Chomsky

“Drawn To Change” is a new Canadian graphic novel that illustrates just this. The book is a collection of stories that focus on the historic struggle of Canadian workers.

The book is edited by The Graphic History Collective and co-edited by Paul Buhle. Both have an extensive list of fascinating titles under their belts.

Spanning from the 1800s to the present, “Drawn To Change” is a collection of firsthand, personal illustrated narratives. Tales of working class Canadians, Aboriginals, the poor, the struggle of women in the work place, domestic workers and immigrants are all featured in the book.

The book is visually wonderful. The styles of artwork within vary greatly.

With each new story comes a different illustrative approach, at times whimsical, at others stark and heavy. Sometimes an artist will utilize an almost naive drawing style and at other times employ a more dark or serious tone. This variety adds to the visual interest and impact of the book.

The first chapter deals with the Canadian branch of “The Knights of Labour,” established in 1869 in Philadelphia. Many Canadians flocked to the KOL as it strived to improve living conditions for the working class. Eventually the KOL’s success in the community and in political organizing posed a threat to the establishment. By 1886, Prime Minister John A. Macdonald included the KOL alongside Louis Riel and Home Rule in a list of “Rocks Ahead” that threatened the Tory “ship.”

One well-known KOL organizer was Lucy Parsons, who went on to be a founding member of the IWW. She once stated, “never be deceived that the rich will permit you to vote away their wealth.”

Another chapter deals with the Spanish Civil War and the fascinating life of Bill Williamson: a Canadian, a Communist, Wobbly and photographer who travelled to Spain to fight on the side of the republic against Fascism.

Another chapter tells the story of Corbin, a small British Colombia coalmining town in the 1930s. The residents endured deplorable living conditions and were forced to shop in grotesquely overpriced “company stores.” By 1935 the workers had had enough and undertook a grueling strike. After police moved in, 60 strikers were injured, 28 hospitalized and 18 workers were sent to prison.

The suppression and violence was so bad that it brings to mind Marx’s writings on the contradictions of capitalism. The organizing of productive forces into owners and workers/employers and employees, two separate groups with vastly opposing interests, is an inherently unstable system with conflict embedded directly into it.

Other chapters tell equally intriguing stories of working class heroism and struggle, from indigenous histories and labour organizing in British Columbia, to the women’s movement in the textile industries of Quebec, to temporary foreign workers struggling to become permanent residents of Canada. It takes us right up to the 1990s and the lessons learned from the “The Days Of Action” in Ontario.

Overall “Drawn To Change” is an extremely well crafted and informative graphic novel. It serves not only as a valuable historical record but provides us with a unique perspective: a history of Canadians, perhaps not that well known, who struggled to create positive change from below.