New Year 2016 started off with a range of important news developments, ranging from the global impact of stock market losses in China, to the escalating tensions between Iran and Saudi Arabia, and neoliberal political advances in Latin America.

Compared to these stories, the militia takeover of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge seems less significant. But the news from Oregon is another worrisome indication that far right forces are on the offensive in many parts of the world, including North America.

The level of armed militia actions in the United States varies over the long run. After a sharp increase during the late 1980s and early ‘90s, this phenomenon dropped off for some years following the 1995 terror bombing of a federal building in Oklahoma City by neo-fascists. The mass murder of 168 people – including 15 kids at a day care and four other children – exposed the militias as vicious killers. But the relentless drumbeat of militarist propaganda in the U.S. over the past decade and a half has given wider political scope for neo-fascist gangs to operate. Despite the media focus on extremist “jihadis”, most violent terror attacks in the U.S. and Canada are committed by ultra-right groups.

This may be particularly true in the western U.S., which has a long and bloody history of colonial genocide to accomplish the theft of indigenous territories. One result has been the spread of white supremacist and “libertarian” ideologies to justify the activities of so-called militias, even to the point of armed insurrection against the U.S. state itself.

As others have noted, these ideologies tend to feed off the popular discontent arising from very real economic and social distress. Many rural areas of the western U.S. suffer from environmental problems and cyclical economic crises which result in high rates of poverty and the dispossession of homes, farms and ranches.

Writing on the People’s World website, Patrick J. Foote reviews the background to “a decades-long movement which began as the Sagebush Rebellion” in response to legislation of the mid-1970s, which placed under federal ownership lands which had previously been opened to homesteading as part of the theft of Native American lands. Ranchers were compelled to pay grazing fees on lands controlled by “Washington bureaucrats”. Developers and industrialists suddenly lost the unfettered “right” to mine or drill on vast areas.

The resulting “Sagebrush Rebellion” was backed by Ronald Reagan, who appointed James G. Watt as Secretary of the Interior to roll back the gains of the environmental movement. Watt blocked the transfer of private lands for conservation and multiplied the areas leased to coal mining companies. In 1983, Watt was compelled to resign after a series of racist statements, but the damage was done. Resource corporations fanned the flames of so-called “grassroots activism” demanding the turnover of all public land to private owners.

These “astroturfing” political tactics soon connected up with the “patriot militias,” creating what Foote calls “the modern tip-of-the-spear” for fringe conservative movements like the Tea Party and racist hate groups. Such strategies resonated in Oregon, which was founded as a “white utopia”and became a hub of neo-Nazi groups.

These movements multiplied after the election of Barack Obama, the first black U.S. President. To attract working class support, such forces make populist appeals to pit manual labour against “intellectuals”, scapegoat minority groups, or attack “international bankers” using coded anti-Jewish language.

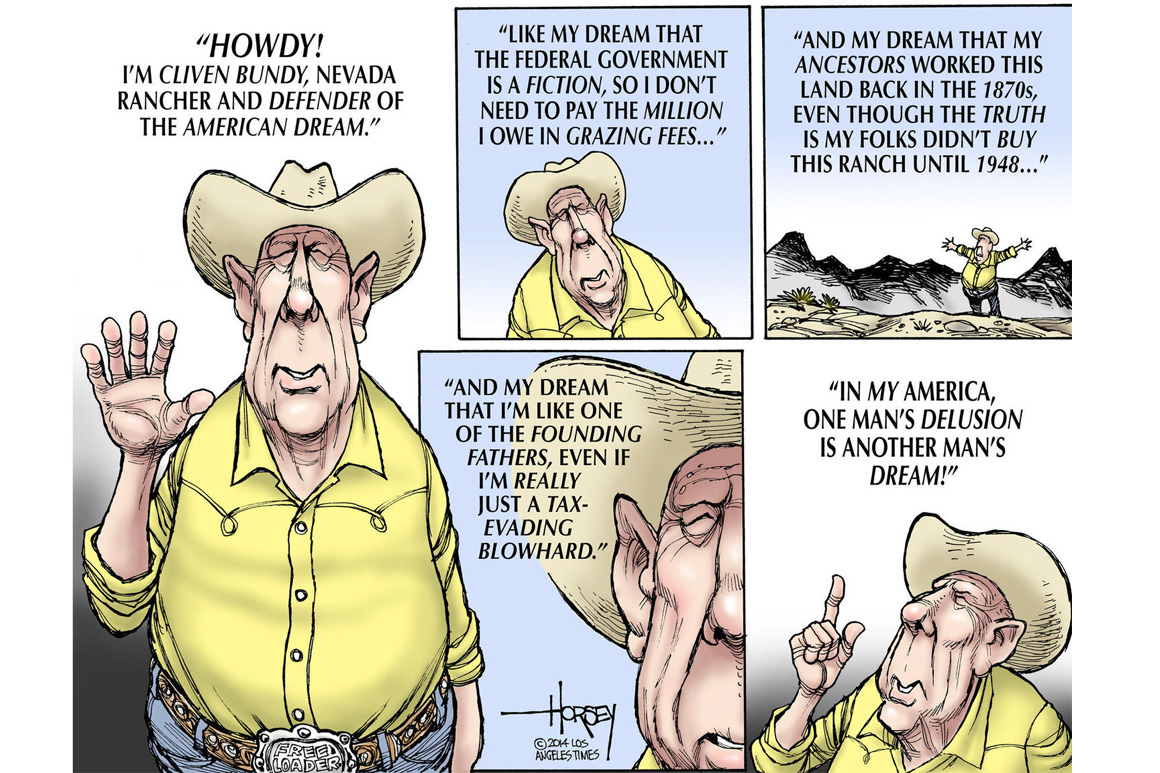

Some, like Nevada rancher Ammon Bundy, who helped instigate the militia occupation in Oregon, are openly racist. Bundy is on record claiming that African Americans “had it better” under slavery, for example.

Not surprisingly, however, these forces repel most Oregon residents. Even many who sympathize with the grievances raised by the Bundys want nothing to do with their violent threats and virulent racism.

Behind all these historical and political factors, the truth is that the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge was actually unceded indigenous territory, long before it was taken over by white ranchers and farmers starting around 1900.

The leaders of the Burns Paiute tribe, whose ancestors fought and died to defend this land, want the militias to get out of the Refuge. Speaking to U.S. media outlets, tribal leaders said in early January that they are still fighting over land use, but are also working with the Bureau of Land Management to save archaeological sites.

“We have good relations with the refuge. They protect our cultural rights there,” said tribal council Chairwoman Charlotte Rodrique.

“They just need to get the hell out of here,” tribal council member Jarvis Kennedy told a crowd of reporters and local residents. “To me they are just a bunch of bullies and little criminals coming in here and trying to push us around over here and occupy our aboriginal territories out there where our ancestors are buried.”

Members of the tribe are descendants of the Wadatika band of northern Paiutes, whose history in the area dates back 9,000 years. Their ancestors lived near the shores of lakes in the U.S. Northern Great Basin, but migrated when those lakes dried up.

The tribe has never ceded its right to the land. In 1868 they signed a treaty with the U.S. government, which promised to prosecute any crime or injury perpetrated by any white man upon the Paiutes. Just eleven years later, the Paiutes say their people were “loaded into wagons and ordered to walk under heavy guard” in knee-deep snow and forced off their land on foot.

“They literally walked our people, children and women off our lands. They had no problem killing us,” Kennedy said.

Inside the Malheur Refuge headquarters now occupied by white militias from out of state, there are important official papers that document the tribe’s history.

“It gets tiring. It’s the same battles that my ancestors had. And now it’s just a bunch of different cavalry wearing a bunch of different coats,” Kennedy said.

There are now about 200 Burns Paiute tribe members, most of whom work hard at odd jobs to survive.

“It’s tough out here. Not a lot of jobs. If any company wants to relocate we’d welcome it,” according to Kennedy.

According to media reports, the tribal leaders agree with the tactics used by the federal, local and state law enforcement authorities, who are waiting out the militias. But they also believe that if they occupied the Refuge headquarters, the government’s response would be quite different.

“We’d be already shot up, blown up or in jail. Just being honest; they are used to killing us,” Kennedy said. “They are white men. That is the difference. That is just how I see it.”