By Stéphane Doucet

Montreal’s mythic status as a capital for culture, resistance and working-class power is slipping away as it loses ground to the forces of neoliberalism and ruling-class hegemony. At the center of this fall is the impact of real estate speculation on the engine of Montreal’s charm: its low-income and working-class tenants and communities.

It’s well-known that Quebec has legal protections for tenants which might make the rest of North America jealous. Rent control has been in place since 1980 and covers all rental units except new builds for a period of 5 years. Tenants can contest rent increases even on a brand-new lease. There are protections against arbitrary evictions, such as when landlords renovate or move into a unit they own.

Some of these comparatively robust rental laws were credited with Montreal having a lower-priced rental market compared to other large cities in Canada over the 1990’s and 2000’s. Now that Toronto and Vancouver prices are said to be plateauing, Montreal and even mid- and small-sized Quebec cities are seeing surging prices while the housing crisis sets in.

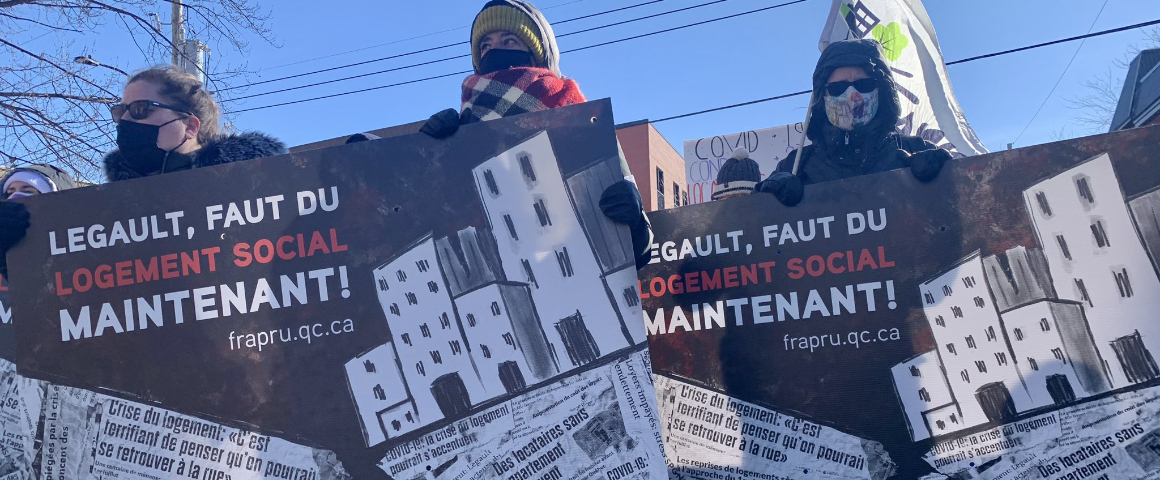

July 1 is moving day in Quebec, the day that a standard lease turns over. This mass moving event makes it easier for housing rights organizations to establish the number of tenants who are leaving their apartments but cannot find a new one. This year, the Front d’action populaire en réaménagement urbain (FRAPRU, Popular Action Front on Urban Redevelopment) estimated that almost 500 households were facing homelessness on July 1, a higher number than at the peak of Quebec’s last housing crisis in 2001. This figure only includes households who reached out for help using official or established housing rights channels whose date FRAPRU can access, and therefore excludes unknown numbers of tenants in crisis.

But there is another side of this. Weeks after July 1, “for rent” signs abound in Montreal despite at least 128 households not having been able to sign a lease. On July 2, a Journal de Montreal article headline declared that “Luxury apartments are still available everywhere” but this cannot refer to the dozens of available units all over working-class and gentrifying neighbourhoods which cannot be called “luxury” at all – rather, they are likely just too expensive for the average tenant. The vacancy rate in Montreal hovers around the 3 percent mark, which the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) describes as a “stable market.” But this doesn’t account for prices or condition, or for more subjective factors like discrimination or location. Housing discrimination, particularly against racialized people and families with children, is being denounced all over the news and social media but official channels are all but useless to challenge the practice.

The CMHC, the federal government’s national housing agency, collects data to analyze the status of local housing markets. An important factor when looking at their data is that their “average” prices are skewed by units that have had successful rent control over longer periods of time. Their figures are used to establish official vacancy rates, standards for “affordable housing” prices and to set policy when events such as housing crises are declared.

In some parts of Montreal, prices are reaching double-digit inflation on a yearly basis. These figures come from the Regroupement des comités logement et associations de locataires du Québec (RCLALQ, a coalition of housing groups and tenants’ organizations) which analyzed more than 60,000 Kijiji ads across the province. The RCLALQ numbers represent what is available for rent, while the CMHC figures broadly reflect what people are paying. In some cases, such as Montreal’s Verdun and South-West districts, available rentals were on average 73 percent more expensive than what the CMHC numbers show as average rents. The provincial average was a difference of 30 percent in price.

What is happening in Quebec? What is driving the current surge in prices? Why isn’t rent control working like it used to? Who is benefitting while masses of people pay the price? How can this be reversed?

Housing operates at the intersection of many different kinds of powers: municipal property taxes meet international banking and investment capital, provincial social housing programs compete with pension fund-backed local real estate developers, and so on. As with virtually all industries under capitalism, the real winners are monopoly capitalists. But that may not be a precise enough response to the questions posed above.

Some researchers point to the financialization of real estate as being a driving force in this new wave of housing struggles. Following the deregulation of financial markets and the emergence of different forms of ownership and speculation on land and housing (such as condominiums and mortgage bundling) the market has boomed and prices have shot up. Powerful players in international finance invest in housing construction but also in property management, leading to a ratcheting up of rents for tenants at the lower end of the ladder.

These factors may seem abstract, and in some ways, they are intentionally so. They are also a bit alien to someone experiencing housing discrimination from an independent, small-scale landlord. Certainly, international financiers aren’t dictating the racist whims of the average landlord in Montreal, Trois-Rivières or Sherbrooke, but the pressures that they create in the market certainly do empower them and create the conditions for their flourishing.

The erosion of rent control in Montreal and Quebec may also be the result of pressures that real estate financialization brings to the market. Housing activists in Quebec have always contested the balance of power between tenants and landlords in the enforcement of rental law. As with virtually all laws, they are only any good if they are widely respected, as enforcement is neither expected nor really possible under the current capitalist regime. Now that the market is shifting, we can see a certain change in the “social contract” between tenants and landlords, with the latter becoming bolder and more cut-throat. Notions of “right” and “wrong” are being slowly sidelined as landlords favour simply doing what they can get away with.

For example, a 2020 study by a local housing committee in Montreal’s Petite-Patrie neighbourhood found that roughly 75 percent of “legal” evictions ended up being either fraudulent or malicious – this despite being a well-defined process within rental law. This fraud and malfeasance is seldom punished, and is never punished enough to make it not worth it for landlords to engage in this behaviour. The social environment which created and was created by the emergence of legal protections for tenants, is becoming passé and is being replaced by the cold logic of the market.

Although financialization looms large behind the emerging housing crisis in Montreal, there are a number of ways it can be slowed down or even reversed. Treating housing like a human right begins with finding housing for those who have none and building social housing that everyone can afford. Since the federal government essentially backed out of building social housing in 1994, wait lists have grown and existing units have deteriorated.

Building social housing doesn’t rid us of the bad actors in finance capital, but it reduces their monopoly in the sector, lowering prices and improving tenants’ position in the balance of power. Municipalities need access to more revenue, particularly from increased taxes on corporations, so that they aren’t entirely reliant on property taxes. This would lower their incentive to promote the infinite growth of property value as their only independent means of raising funds, which is a significant factor contributing to the current crisis.

Quebec is going through a housing crisis, and nobody yet knows how bad it’s going to get. The so-called progressive municipal administration of Valérie Plante is bulldozing homeless encampments while rents are skyrocketing. We need to understand the roots of the crisis and go beyond spontaneous denunciations of gentrification or slumlords, as awful as they are. The solutions to the crisis exist, and it’s up to the working class to force their implementation.

[Photo: FRAPRU]

[hr gap=”10″]

Get People’s Voice delivered to your door or inbox!

If you found this article useful, please consider subscribing to People’s Voice.

We are 100% reader-supported, with no corporate or government funding.