“We Bolsheviks participated in the most counterrevolutionary parliaments, and experience has shown that this participation was not only useful but indispensable to the party of the revolutionary proletariat, after the first bourgeois revolution in Russia (1905), so as to pave the way for the second bourgeois revolution (February 1917) and then for the socialist revolution (October 1917).”

Lenin, “Left-Wing” Communism: An Infantile Disorder

From its very beginnings a century ago, one of the distinguishing features of the Communist Party of Canada has been its understanding of the parliamentary arena as a key element of the class struggle. Weaving a line between the careerism and opportunism that characterizes social democrats, and the outright rejection of electoral struggles by left sectarians, the communist approach has been to combine parliamentary and extra-parliamentary tactics in an ongoing effort to unite and build the working class movement.

Electoral campaigns do not need to result in winning a seat in order to be successful. There are myriad examples of electoral movements whose victory has been the organization and mobilization of the working class and the masses around a radical, progressive program that is intimately connected to the (decisive) struggle in the streets and workplaces.

That said, there have been many occasions in which communists have been elected in Canada and have been able to use that platform to further advance the class struggle.

Municipal

Municipal politics have been a particularly strong focus for the Communist Party, reflecting the closeness of local politics to the working class. It is an area of work that continues to be a priority in the present day. There are far too many examples of communists elected to municipal office to list in one article, but there are some that stand out:

The very first person elected in North America under the red banner of the Communist Party was William Kolisnyk, in 1926 in Winnipeg. Just five years after the party’s founding, Kolisnyk won election to Winnipeg’s city council and remained in office for four terms until 1930. He pressed for public transit, improvements to unemployment relief and workers’ rights. Notably, he is credited with helping the city’s municipal employees to unionize, including by advocating on their behalf as a member of council.

In 1933, in the depths of the Great Depression, the Alberta town of Blairmore elected a communist majority to its school board and council, including the mayor. Collectively, they were colloquially referred to as the “Red Miners Slate.” They were veterans of a bitter 1932 strike between the communist-led Mine Workers Union of Canada and West Canadian Collieries, which used 100 strikebreakers, under a 200-gun RCMP escort, to defeat the 350 workers. But, a year later they became the first communist council and school board in Canada. They retained control for a decade, during which time they instituted police and tax reform, restored relief payments to unemployed workers and expanded the local public health service. Perhaps their most well-known reform was to change the name of Blairmore’s main street to Tim Buck Boulevard, a decision that was reversed by the next council.

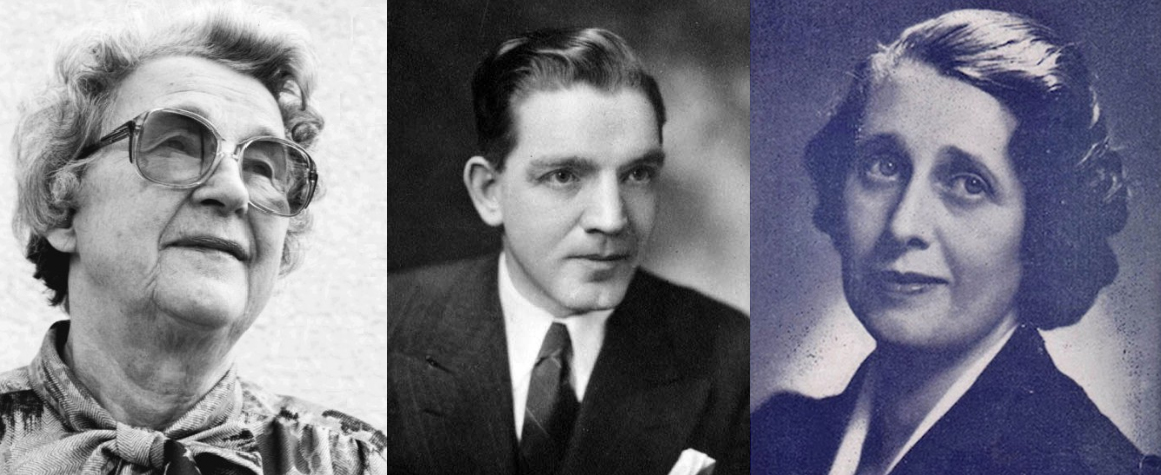

Through five decades following World War 2, communists were a leading force in Winnipeg’s municipal politics, particularly through the Labour Election Committee (LEC). The LEC elected many progressive candidates, including communists such as Andrew Bileski and Joe Zuken. Long-time Communist Party member and feminist organizer Mary Kardash had a spectacular political career in Winnipeg, winning election to the school board in 1960 and being re-elected until 1970, and then again from 1977 to 1986. A People’s Voice article from October 2011 paid tribute to her: “As a school trustee, Mary was a tireless fighter for a high-quality education for all children, especially those from low-income families. She was on the cutting edge of struggles for school breakfast programs, better childcare, and many other reforms. Her efforts focused particularly on working with Indigenous groups to tackle the poverty faced by thousands of Indigenous children in Winnipeg. The St. Cross Child Care Centre of Winnipeg was renamed the Mary Kardash Child Care Centre in her honour in 1995.”

Communists in Vancouver worked with labour and democratic movements to build up the Committee (later Coalition) of Progressive Electors, through which a number of communist school trustees and councillors were elected, including well-known councillor Harry Rankin. Another was longtime housing and tenant advocate Bruce Yorke. In 1968, Yorke helped organize the Vancouver Tenants Council, which used rent strikes and other militant actions against landlords, as well as lobby efforts, to win reforms including the right for tenants to vote in municipal elections. Yorke was elected to Vancouver council in 1980 and re-elected an impressive four more times. He was never voted out of office but retired in 1991 for health reasons.

Toronto has had many communists elected over the years, especially at the school board level where trustees like Edna Ryerson, Ruth Weir and Elizabeth Rowley worked to defend and strengthen public education. One of the most important contributions was in 2002, during the Conservative provincial government of premiers Mike Harris and Ernie Eves. Harris had introduced sweeping restructuring of Ontario included radical changes to school board governance and funding, removing their ability to raise funds and removing over $1 billion from the education system. In 2002, the provincial government instructed the board to prepare a balanced budget, but the inadequate funding made that impossible. Veteran communist trustee Elizabeth Hill had been fighting the Conservative government since its election in 1995 and was described in the press as “the unofficial leader of the left on the school board.” Hill and others in the progressive bloc wanted to defy the province’s orders but they were one vote short of a majority. Opportunity came in the form of a byelection, which was won by another communist, Stan Nemiroff. His campaign was critical – both the right and the left knew that the balance on the board was in question – and it attracted a large mobilization of labour and progressive activists from across the city. With Nemiroff’s victory, the left had a majority on the board and voted against the balanced budget directive. Despite public support for their action, they were put under provincial supervision. Ironically, the government-appointed supervisor was also unable to balance the budget.

Provincial

Communist electoral success at the provincial and federal levels has been more limited. In no small part, this is the result of state harassment and repression – the Communist Party of Canada has been illegal for approximately one-third of its history. Nonetheless, there have been notable breakthroughs.

Arguably, the first Communist Party member to be elected to provincial government was Phil Christophers, in Alberta in July 1921. Christophers, who was a miner from Blairmore, was at the founding convention of the Workers Party of Canada (a legal public entity of the Communist Party, which was an illegal organization at the time of its founding in May 1921) but ran in the election with the Dominion Labor Party (DLP). This organization was affiliated with the Canadian Labor Party (CLP), a reformist party which the Communist Party briefly supported as part of a united front against capital. At the time of his election, Christophers was the Alberta provincial spokesperson for the Workers’ Party. He was re-elected in the 1926 election.

James Litterick is widely credited as being the first person elected on a Communist Party ticket to a state or provincial legislature anywhere in North America. Litterick joined the Communist Party of Canada in Vancouver and was one of the founders and leaders of Vancouver Unemployed Workers’ Association at the beginning of the Depression. He held a number of positions in the young party, including district secretary in British Columbia, and he assumed some of the General Secretary responsibilities when Tim Buck was arrested in 1931 and imprisoned until 1934. Litterick became Manitoba secretary in 1934 and was elected to the provincial legislature in 1936 on the Communist Party ticket. In office, he fought to shift the tax burden from working people to corporations, pressed for increased unemployment relief payments and for job creation through infrastructure and public works spending, and introduced a motion (which was defeated) to create public health insurance in Manitoba.

In 1940, the Communist Party of Canada was declared illegal by the Mackenzie King government, and Litterick was expelled from the Manitoba legislature. He went into hiding, was the subject of a RCMP hunt and was eventually imprisoned. Soon after leaving prison in 1943, he went missing and was never found.

One of the best known elected communists in Canada is Manitoba’s William (Bill) Kardash, who was also the partner of Mary Kardash. Bill joined the Communist Party in Saskatchewan during the Great Depression and became an organizer for the left-wing Farmers’ Unity League. He joined the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion, the Canadian component of the International Brigades who fought to defend republican Spain against fascism. In 1941, Bill was elected to the Manitoba legislature as a Workers Party candidate (the Communist Party was banned) and then re-elected in 1945 for the Labor-Progressive Party (the Communist Party’s legal political organization from 1943 to 1959). Enormously popular among Winnipeg’s working class, Kardash swept to victory again in 1949 and 1953. He was finally defeated in the 1958 election, largely due to the elimination of proportional representation in Manitoba.

For nearly two decades in the legislature, Bill Kardash waged a determined and relentless fight for the interests of the working class in Winnipeg and internationally. When he died in 1997, NDP MLA (and later Manitoba Premier) Gary Doer stated, “Truly, it can be said that Mary and Bill were political and social powers in the north end of Winnipeg, people that fought tirelessly for working people and their families. Together, whether it was on the school boards through Mary, or Bill in this Legislature, they fought on behalf of poor people every hour of the day.”

Ontario had two communists elected to its provincial government, who served during the same period of time and from neighbouring ridings in Toronto. A.A. MacLeod joined the Communist Party in Nova Scotia, while working on the election campaign of veteran union leader and communist J.B. MacLachlan. Soon afterwards, he helped found the Canadian League Against War and Fascism in 1934. He had a long record as a peace activist and helped organize the Canadian Peace Congress after WW2. MacLeod was elected to provincial parliament in 1943, after being endorsed by a long list of trade unions representing a range of sectors, ranging from manufacturing to building trades to public employees. MacLeod was re-elected twice, in 1945 and 1948, but defeated in 1951.

Joining MacLeod at Queen’s Park was J.B. Salsberg, a garment worker turned union organizer who was very popular in Toronto’s working class Jewish community. He was elected to municipal council in 1938, and five years later he won a landslide victory in the 1943 provincial election. Salsberg was re-elected three times and finally defeated in 1955.

Since the Communist Party was illegal at the time of the 1943 election, MacLeod and Salsberg ran as “Labour” candidates, although it was well understood that they were communists. Within days of their election victory, the Labor-Progressive Party was formed, and they agreed to represent it in the Ontario legislature. Both men were highly respected – Tory Premier Leslie Frost once said of them, “Those two had more brains between them than the rest of the opposition put together.” Among their lasting accomplishments was the 1944 Racial Discrimination Act, which Salsberg introduced in response to racist and anti-Semitic prohibitions at public pools.

Federal

Dorise Nielsen was the first member of the Communist Party to be elected to federal parliament. In the 1940 general election, she was one of two candidates from the United Progressive Movement (UPM) to win a seat in Ottawa. The UPM was a popular front organization that united communists, social democrats and other progressives. Nielsen, who represented the Saskatchewan riding of North Battleford, was the only woman elected to that parliament. From her seat in the House of Commons, and by maintaining contact with Communist Party leaders in Montreal who had not been arrested, she became a key spokesperson for the Communist Party at a time when it was banned.

In the 1945 federal election, Nielsen ran for the Labor-Progressive Party but was defeated after a nasty campaign that was characterized by anti-communism and red-baiting.

In 2017, the Saskatoon StarPhoenix and Regina Leader-Post published stories of 150 Saskatchewan people who helped shape Canadian history. They wrote that Dorise Nielsen “was a crusader for children’s welfare, civil liberties and the fight against poverty — especially in depression-ravaged west — at a time when the government was focused on war funding which far exceeded spending on social causes.”

Soon after Nielsen’s breakthrough, Fred Rose became the second communist to win a seat in the House of Commons, representing Montreal’s Cartier riding. In getting elected for the Labor-Progressive Party, he beat CCF national secretary and future NDP leader David Lewis. A friend and comrade of Norman Bethune, Rose was a well-known anti-fascist who campaigned for workers’ rights and against anti-Semitism. In the middle of WW2, in a riding that was almost 60 percent working class Jewish voters, his campaign struck a chord. Two years later (and armed with an endorsement from American musical legend Paul Robeson) Rose was re-elected with a 30 percent increase in his 1943 vote. As a Member of Parliament, Rose came through with his promises, proposing the first federal medicare legislation and the first anti-hate legislation.

Not even a year into his term, Rose was caught up in the rapidly spreading Cold War. Accused of spying for the Soviet Union, the media immediately proclaimed him a traitor. After a controversial trial he was convicted of conspiring to turn over information about an explosive to the USSR (information that the Canadian government wanted to give) and sentenced to a prison term one day longer than the length required for his expulsion from the House of Commons. He was released from prison after 4 and a half years and went to Poland; the Canadian government revoked his citizenship in 1957 and he was never able to return to Canada.

These are just a few of the many stories of communists who were elected to different levels of government across Canada. There are thousands more narratives of communists who have campaigned in elections but not won a seat. Some of their experiences have been positive and uplifting, others heartbreaking and tragic, and many have contained humourous delights.

But all of them have been heroic. Whether they were a Party leader or a trade union veteran or a poor and unemployed labourer, regardless of the level of government for which they campaigned and irrespective of the turns their political lives may have taken in the years after, each of these people undertook a revolutionary task that was, to paraphrase Lenin, vital to the Communist Party, to the working class fight for meaningful reforms and to the revolutionary advance toward socialism.

They were and continue to be an indispensable element of the class struggle in Canada.

[Editor’s note: the original version of this article mistakenly stated that Phil Christophers was at the founding convention of the Communist Party of Canada.]

[hr gap=”10″]

Get People’s Voice delivered to your door or inbox!

If you found this article useful, please consider subscribing to People’s Voice.

We are 100% reader-supported, with no corporate or government funding.