Economic developments have brought sweeping changes to the character of work. The rapid growth of precarious employment and the rise of the gig economy are among the most challenging factors that affect workers’ ability to organize and struggle collectively. Confronting these challenges has required new approaches by labour movements. In this three-part series, People’s Voice examines how workers and unions are navigating the stormy seas of the new economy.

Economic developments have brought sweeping changes to the character of work. The rapid growth of precarious employment and the rise of the gig economy are among the most challenging factors that affect workers’ ability to organize and struggle collectively. Confronting these challenges has required new approaches by labour movements. In this three-part series, People’s Voice examines how workers and unions are navigating the stormy seas of the new economy.

For video game players, “boss” refers to a computer-controlled opponent who is much more powerful than normal enemies, and whose defeat often results in a new level.

For game workers, the boss could be any of the approximately 500 companies across Canada that employ over 20,000 artists, designers, engineers, programmers, and quality assurance workers. The largest studios are huge, individually employing anywhere between 800 and 1500 workers. It’s a big industry that plowed nearly $4 billion into the Canadian economy in 2016 – for comparison, that’s about the same as the country’s railway and transit supply industry – and is growing by double digits every year.

So, again, more powerful than normal enemies, but whose defeat also brings things to a whole new level.

Typically, game workers are young people; their average age is 31 years, a decade younger than the average worker in Canada. The jobs can be attractive – game workers tend to enjoy games, so have the rare opportunity to work on a product they personally feel passionate about. Furthermore, the industry constantly boasts that the average salary is over $70,000, which is a pretty attractive figure for most workers, let alone ones under 35.

But is the game industry really this wonderful – a hip, well-paid and creative paradise?

“God no!” says Daniel Joseph, an organizer with the Toronto Chapter of Game Workers Unite (GWU), a worker-led organization that works to connect game workers with union activists. “It’s a particularly poor working environment where we see huge, highly capitalized corporations maintaining a very aggressive, exploitative workplace. People work very long hours, especially during Crunch – the period when a team crams to complete a game in time for its scheduled release. It’s not uncommon for people to be putting in 60 to 100 hours each week, for weeks and even months on end.”

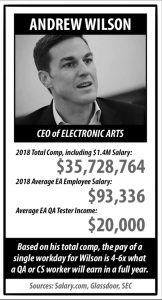

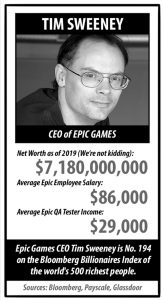

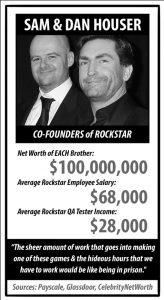

As to the high wages, Joseph says that these are purposely overstated. While senior programmers and engineers do often make six-figure salaries, many more game workers make much less than that. Quality Assurance (QA) is particularly poorly paid, with the median salary for junior testers being around $22,000. Data from GWU Toronto studies show that industry-cited salary figures for QA are consistently half of what people are actually earning. Contrary to corporate claims, game industry wages are much lower than the rest of the tech sector.

Furthermore, a huge amount of game work is project-based contracts, so workers may be employed for just a few weeks and then dropped without compensation. According to industry insiders, some studios have more than 50% of their workforce made up by contractors.

As with other industries in the gig economy, many game industry contractors rely on digital “transaction platforms” for their work, a corporate practice that accelerates the replacement of regular jobs by contracts. Platforms have also been proven to contribute to reproducing racist and sexist patterns in employment, as online contract ads are typically “screened” toward specific target demographics.

And then there’s Crunch. Even among the tech sector, the game industry is notorious for its mandatory uncompensated overtime. Last year, Rockstar Games co-founder Dan Houser boasted in a magazine interview that one of the company’s project teams had “worked several 100-hour weeks” when they were finishing Red Dead Redemption 2. The “march or die” management approach, and corresponding marketing pitch, paid off mightily for Rockstar: the game sold 25 million copies within months and generated $725 million in sales during its opening weekend. But the costs of Crunch on workers are enormous: burnout, doctor-mandated stress leave, and mental and physical breakdown are disturbingly common.

And then there’s Crunch. Even among the tech sector, the game industry is notorious for its mandatory uncompensated overtime. Last year, Rockstar Games co-founder Dan Houser boasted in a magazine interview that one of the company’s project teams had “worked several 100-hour weeks” when they were finishing Red Dead Redemption 2. The “march or die” management approach, and corresponding marketing pitch, paid off mightily for Rockstar: the game sold 25 million copies within months and generated $725 million in sales during its opening weekend. But the costs of Crunch on workers are enormous: burnout, doctor-mandated stress leave, and mental and physical breakdown are disturbingly common.

You’d figure that all of this would add up to an industry that would be fairly quick and easy to unionize.

Not so, according to Joseph. “You do have, on the one hand, this intersection of exploitation and issues of oppression, that people are pretty aware of. And you have related industries, like film and theatre, that are heavily unionized so you kind of expect a high degree of cross pollination. But in reality, there are specific challenges that we need to overcome in order to successfully unionize in this environment.”

Some of the difficulties are legislative. In a number of provinces, for example, labour legislation includes exemptions for information technology workers, excluding them from daily or weekly work limits, eating and rest periods, and overtime pay. For game workers who rely on transaction platforms, one of the key challenges is getting the platform treated as an employer. As these barriers are overcome, the results will help provide a valuable “road map” for efforts to organize the game industry and other sectors that are new to unionization.

Another difficulty is workforce turnover. The combination of precarious employment and a high-stress environment means that a lot of game workers leave in short order. A survey done last year, based on data from LinkedIn, showed that the tech sector has the highest turnover rate of industries, at 13.2%. Notably, within the tech sector, the game industry had the highest turnover rate, at 15.5%. By comparison, the average turnover across all sectors was 10.9%.

But a more fundamental challenge, observes Joseph, is a generational divide in which many young workers simply don’t identify with unions. “There’s been a long stretch of time since the union movement had strong organizing campaigns, and so this whole industry and area of work have grown up in a vacuum. Sure, lots of game workers know what unions are and what they’ve accomplished, but they tend to view that as something that happened in another time. Unions exist but the process of unionization is quite a foreign idea. If young workers have experience with union, it’s usually because they worked somewhere that was already organized. There’s a big difference between getting a job in a union workplace and actually joining a union.”

He notes that this divide was also felt by the trade union movement who seemed unsure, at best, of how to approach game workers. “To organize this industry, you need a group of dedicated, politically engaged people. You’re in it for the long haul so it’s a real commitment from the trade union side.” Over the past few years, the labour movement has deepened its understanding of the industry and is taking a much more engaged approach to the fight. GWU has developed dynamic and active relationships with a number of trade unions in Canada and in countries around the world.

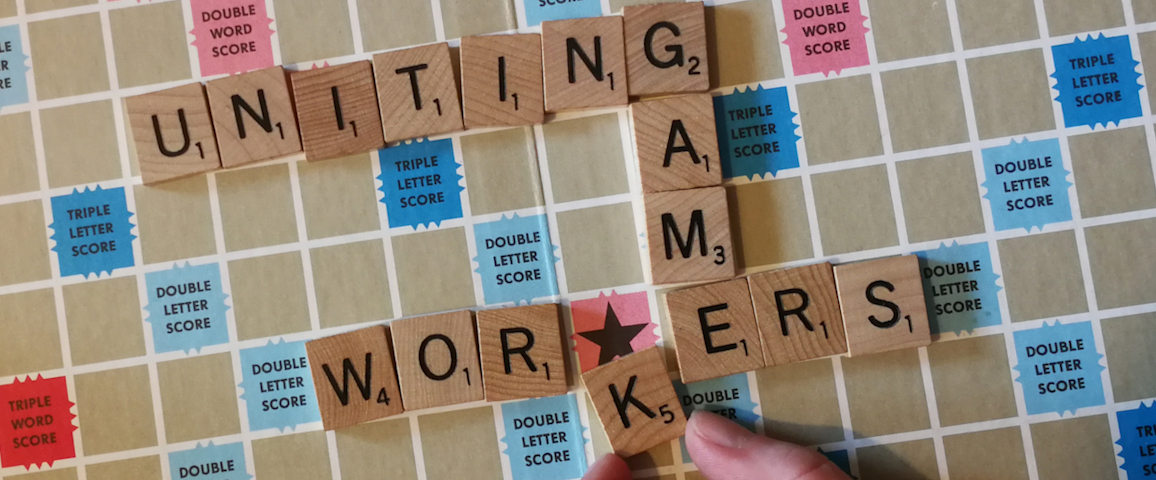

Game Workers Unite is not a union. It’s stated purpose is “to connect pro-union activists, exploited workers, and allies across borders and across ideologies in the name of building a unionized game industry.” It is a non-union part of the broader labour movement whose key role lies in its ability to educate game workers and move them toward collective action. GWU produces material about labour relations, about unions and contracts, about workers and contractors, and places all of this into the context of the game industry. Its publications and resources are produced by game workers, so they have an inviting look and feel. Unlike a lot of trade union communication to young workers, there’s nothing condescending or simplistic here – it’s unapologetically political. This is education for collective action.

GWU also focuses its efforts on game industry venues, including industry magazines and conferences, where game workers tend to be. In the process, the organization keeps its finger on the pulse of key issues and debates, and works with the union movement to respond in a progressive, collective manner.

The organization is just over a year old and has made a tremendous impact on the labour movement in a short time. Joseph is confident that the group’s unique approach to labour struggle is paying off. “Game Workers Unite is about bridging the gap between, on the one side, workers who don’t know about unions and, on the other side, unions who are not out there organizing. GWU began with the efforts of workers themselves, so it has a lot of credibility.

“Really, it’s just the same kind of campaigning that workers have relied on throughout history, to build strong unions and fight the class struggle.

“I am confident that, within the next couple of years, we’ll see one of the big studios in Canada unionized.”