Radical Housewives: Price Wars & Food Politics in Mid-Twentieth-Century Canada

Julie Guard

University of Toronto Press (2019)

Review by Manden Murphy

Working people are living through the worst cost of living crisis in a generation. Food prices have risen precipitously, and essentials like cooking oil were up 26 percent in 2022. The price of home heating and gas at the pumps reached record levels last year. Rents across Canada rose 12.4 percent in the same 12 months. At the same time real wages in Canada have fallen by 3 percent, due to inflation.

Simply put, there has never been a more appropriate time to draw lessons from our progressive past to strengthen the fight back to roll back prices on essentials and win real concessions for working people.

Julie Guard’s Radical Housewives: Price Wars & Food Politics in Mid-Twentieth-Century Canada provides such a lesson. This in-depth and rigorously researched account of Canada’s Housewives Consumers Association (HCA) maps the successes and gains won through this grassroots women-led organization, while putting its trials and tribulations into historical context.

The HCA was a community-based women’s organization with cross-pollination from the Communist Party of Canada/Labor Progressive Party’s membership and the social democratic Co-operative Commonwealth Federation that, from 1937 until the early 1950s, led a broadly based popular movement for state control of prices.

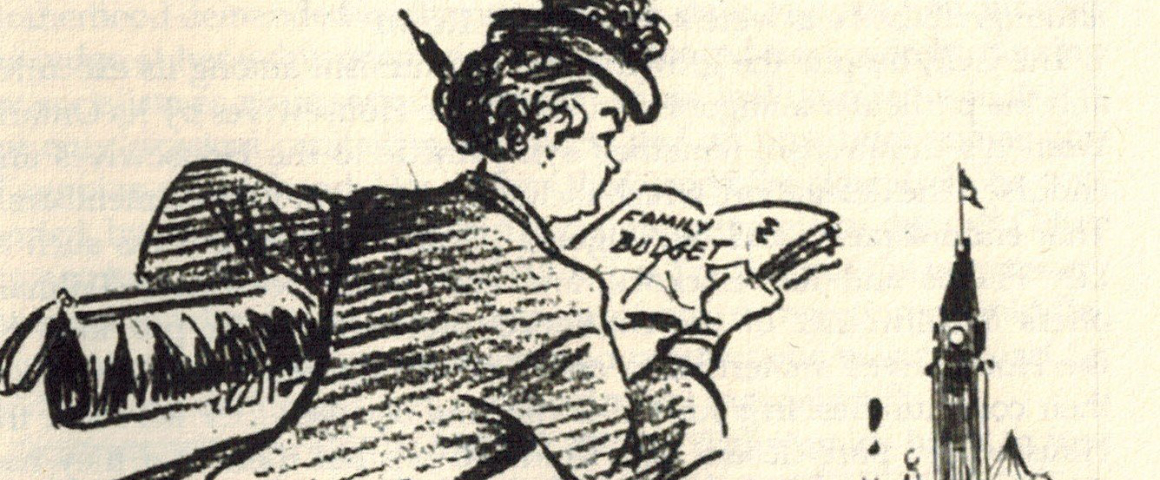

As radical consumer activists, the Housewives engaged in gender-transgressive political activism that challenged the government to protect consumers’ interests rather than those of business, while popularizing socialist solutions to the economic crises of the Great Depression and the immediate postwar years.

It’s a history that critically examines an all too often ignored component of political history. Namely, the critically important role women have played as mothers, workers, immigrants and political agents in shaping progressive politics in Canada.

But it is a complex and messy history. Guard repeatedly describes the Housewives’ maternalism as an important political tactic with an Achilles heel. Their maternalism was a “genuine expression of their identities as wives and mothers and integral to their political activism.” This, Guard argues, shielded them from the rampant “red baiting” that was part of the Canadian political landscape at the time, and made them palatable to a vast cross section of working-class women and homemakers.

However, this same maternalism made their movement vulnerable to reactionary attacks. Demeaning and sexist mainstream news reports often described the Housewives as “attractive” yet “determined and articulate.” Business interests focused on how the Housewives’ “attacks” on capitalism and the state supposedly “promoted an unnatural subversion of genuine motherhood … by corrupting citizenship and promoting moral decay.” By meeting their maternity head on, business interests hoped to highlight the moral subversion “inherent” to the HCA. It failed.

As Guard points out, despite these attacks, the Housewives’ maternalism was an extremely effective tool for political agitation and a temporary antidote to the anti-communist attacks that devastated the movement in the years to come.

Anti-communism had been with the HCA since its founding. Occasionally this surfaced as minor ruptures inside the organization; however, these were never terminal. Most of the non-party-affiliated Housewives recognized that women with experience in the Communist Party were some of the most effective organizers and that their work within the HCA was inspired by their genuine concerns for working people and their families.

But as the Housewives moved into the second half of the 1940’s this cross-pollination with known communists became the focus for big business, which found it could manufacture sympathy as fears of Soviet communism hit hyperbolic proportions during the early days of the Cold War.

This shift in emphasis by big business sought to prove that the HCA was nothing more than a communist front. In the process, the Housewives’ humanity became collateral damage. As Guard demonstrates: “In their translation from genuine housewives into subversives, they were stripped of not only their maternalism, but also their protective femininity … the Housewives were publicly redefined as subversives and communists and thus not entitled to be treated with respect.”

The fact is, as Guard makes clear, communists were some of HCA most effective members. But to describe it as a front was not only disingenuous but did a disservice to the broad appeal of their aims. As an HCA activist observed: “if the [HCA] was really dominated by Communists, then there are a lot of Communists in Canada.”

Guard highlights the HCA’s research which demonstrated how effective government price controls were in bringing down inflation and the cost of living for working people during WW2: “price ceilings … stopped war-induced inflation in its tracks. During the first two years of war … the cost of living [increased] 18%. But price ceilings … ended inflation by fixing the retail price of virtually all goods.”

With that in mind the HCA orchestrated street performances, boycotts, countless petition drives, letters to MPs, delegations to Ottawa and educationals, and produced endless literature advocating for price controls during “peacetime”. The HCA enjoyed mass support and won many victories such as being invited to sit on the Wartime Prices and Trade Board and receiving endorsements from the Canadian Congress of Labour and the Trades and Labour Congress.

Guard’s book makes it clear that the Canadian state and its business interests were terrified of the mass support these women had generated in such a short amount of time. It’s a testament to their organizational capacities and their clear vision for a more equitable future for working people.

Radical Housewives is an indispensable read at a time when the Canadian government would sooner provide Loblaws – which has a track record of price-fixing and who is experiencing record profits – with a $12 million grant to refurbish old refrigerators than provide rent/price controls working people so desperately need. As working people continue to struggle to make ends meet, we can look to the Radical Housewives to strengthen our fight to roll back prices on food, fuel and rent.

Get People’s Voice delivered to your door or inbox!

If you found this article useful, please consider subscribing to People’s Voice.

We are 100% reader-supported, with no corporate or government funding.