By Corinne Benson

Environment and Climate Change Minister Steven Guilbeault announced in mid-August that the government was developing regulations to allow “treated” tailings wastewater to be drained into the Athabasca River as early as 2025, when the current tailings pond will run out of capacity.

In response, the Council of Canadians and Indigenous environmental organization Keepers of the Water have organized a series of webinars to inform people of the problems this will pose. The first, “Tailings Ponds: Past and Present,” was held on October 5.

Opening speaker Paul Belanger gave a great summation when he said, “We could have had this symposium twenty years ago, but we were kept in the dark by media and government more interested in maximizing profit and hiding the fact that there was a growing toxic monster – far away in the north, in a cold place called Fort McMurray.”

Although previous Alberta provincial governments had searched for better ways to deal with waste from bitumen processing, things turned for the worse in 2000. That year, Ralph Klein reorganized the Alberta Oil Sands Research Authority (AOSTRA) into a government department called Alberta Energy Research Institute (now Alberta Innovates). “In this change, independent research was lost, and the work on tailing pond reduction and treatment was no longer on the agenda,” said Belanger. “Research was then directed by industry in this new research arm.”

At the same time, in response to industry requests, Klein reduced oil and gas royalties. When his successor Ed Stelmach tried to reverse this policy, the industry complained that it was too expensive and Stelmach’s directive was cancelled by the next Alberta premier. It is easy to see who runs the show here. There is no better example of what the Communist Party describes as state monopoly capitalism, in which the state and business are married and become one and the same.

What are the consequences? Keepers of the Water says that “releasing tailings effluent will not only have a detrimental effect on life within the Arctic Ocean Drainage Basin but will also significantly impact what little environmental protections are left for life-giving water across the settler state of Canada.” The harmful effects of oilsands production and leaking toxic tailings ponds include low water levels and loss or contamination of critical species which forces Indigenous people off their own land.

Belanger concludes that Alberta has the world’s largest industrial waste site. He also discussed some current industry efforts to improve the situation. These include a pilot project by Syncrude company to “use the waste petroleum coke from the Fort McMurray upgrader as a kind of charcoal filter to clean up the tailings pond water. This clarifies the water but leaves a high level of salt and about 20 ppm of naphthenic acids and a few other substances.” Even Syncrude project head Warren Zubot admits that using “petcoke” causes cadmium to leach into the “filtered” water.

Naphthenic acids are toxic and are the prime suspect in the higher-than-normal incidence of rare cancers in Fort McMurray and Fort Chipewyan. According to the Alberta Cancer Board, residents of Fort Chipewyan, who live 200 kilometers downstream from the oilsands, were 30 percent more likely to have rare cancers than expected by the provincial average.

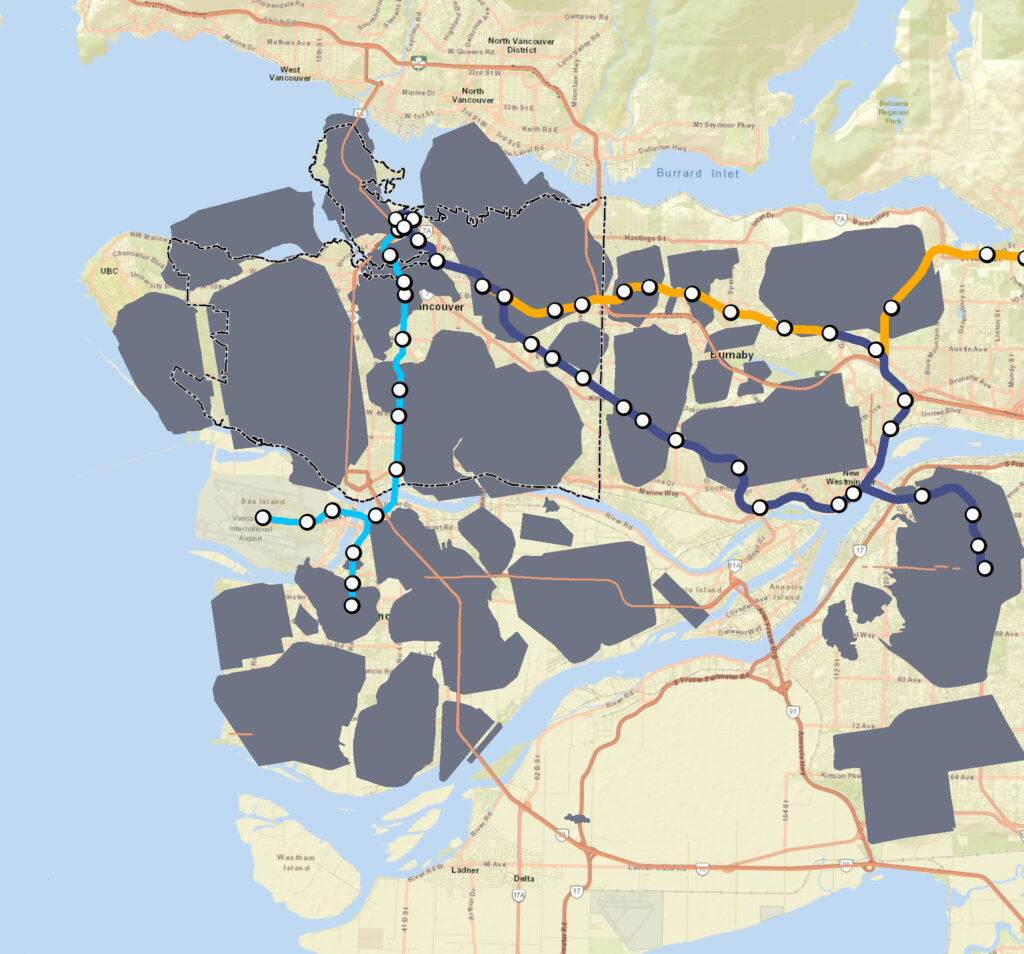

Gillian Chow-Fraser from the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society (CPAWS) spoke to the symposium about the size of the “ponds” and noted the deceptive use of the word. Their volume grew by 40 percent between 2010-2015, just after a new directive was introduced to try and curb tailings. By 2020 the fluid tailing area covered over 120 km2 and the total tailings area covered 300 km2. To visualize this, CPAWS superimposed the tailings area over a map of Vancouver, showing that the ponds are more than 2.5 times the size of the city (see image below).

Each year, tailings ponds leak about 39 million litres into the surrounding environment. This includes the Muskeg River which is less than a kilometer away from a leaking pond. Chow-Fraser noted that talk of reclaimed tailings ponds is a myth, as none have yet been officially reclaimed.

One part of this picture hit the mainstream press, due to the efforts of the Mikisew Cree First Nation which in 2016 petitioned the World Heritage Committee to list the area of Wood Buffalo as a World Heritage Site in Danger. The joint provincial-federal Oil Sands Monitoring Program cut funding from several Wood Buffalo focused projects, including the Tailings Risk Assessment in 2019, with the Alberta government claiming that existing tailings regulations were sufficient. Yet the very critical area of the Peace Athabasca Delta would be very threatened by any release of treated tailings ponds effluent. All indications are that the monitoring program is in the back pocket of business.

Mandy Olsgard from Integrated Toxicology Solutions also spoke to the symposium about inadequate monitoring, stating that “health risks to wildlife that contact tailings ponds are unknown” and that “oilsands monitoring does not include tissue residue monitoring in wildlife species beyond research.” When discussing current threats to the groundwater – and there has been approved seepage of chemicals from tailings ponds into the groundwater – Olsgard said that the “Oil Sands Monitoring Program reporting is incomplete and often contradictory.” Her greatest fear is the closure and reclamation plans for the tailings.

Here again, there is a spectre of lack of government oversight, with Olsgard saying that that “tailings management does not include health risk reclamation criteria” and reiterating that “environmental policy and regulations do not require or consistently assess surface water for risks to human health.” The ground water is known to have been contaminated but we are uncertain about the surface water.

The people of Alberta, in their excitement for work that pays well and supplies the coffers of the province with some money, have been deprived of a great deal of information on the costs of this endeavour to their land and health. Those expected to pay the highest price are the Indigenous people of northern Alberta, which is the focus of the next symposium.

Photo: CPAWS website

Get People’s Voice delivered to your door or inbox!

If you found this article useful, please consider subscribing to People’s Voice.

We are 100% reader-supported, with no corporate or government funding.