By Doug Allan

The Ontario Financial Accountability Office (FAO) says that, with inflation, real wages in the public sector will decline 11.3 percent over the three-year period 2021-22 to 2023-24.

This would radically deepen the trend towards lower wages during the last ten years. The FAO reports that since 2011, the average annual salary for the Ontario public sector employees (defined here as employees of schools, colleges, provincial government, provincial agencies, and hospitals) has increased by $10,385 – or 1.6 percent on average annually. This is the lowest increase of all the sectors and lower than inflation, which averaged 1.8 percent per year. Over the ten years that would be about a 2 percent pay cut.

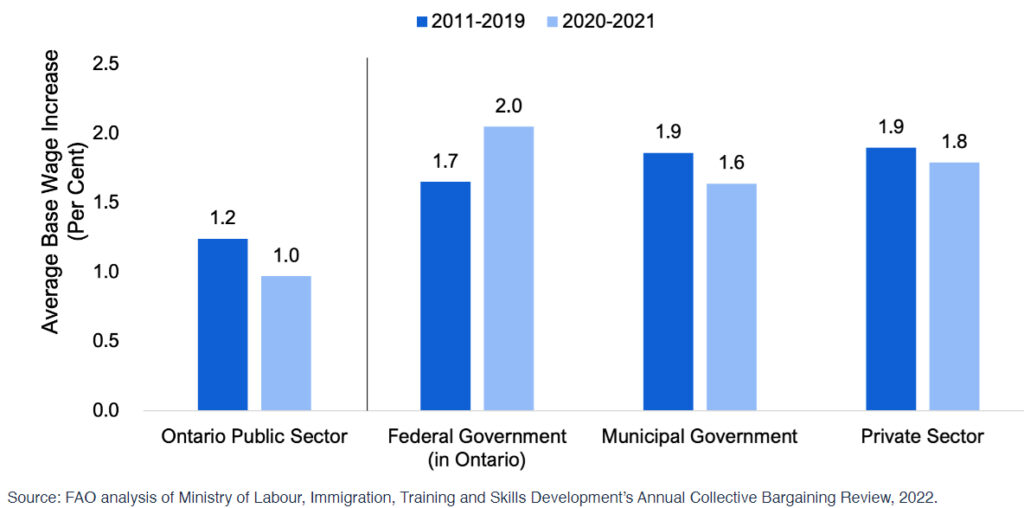

The FAO reports that wage settlements were the lowest in the provincial public sector over the last decade:

Hospital Wages Especially Challenged

The FAO predicts hospital wages will increase even less than in the public sector – just 1.2 percent annually over the five-year period 2021-22 to 2026-27 compared with 1.7 percent in the public sector. Both are well below inflation. Far from solving the staffing shortages choking the hospital system, this will make hospital work much less attractive as an employment option.

Employment Growth

Going forward, the FAO estimates that the province’s total spending on salaries and wages for Ontario public sector employees will reach $56.9 billion by 2026-27, representing an average annual growth rate of 3.4 percent over the five-year period. This is the increase in total public sector wages based on both wage and employment growth. The FAO estimate of 3.4 percent projects that employment will grow 1.7 percent annually and that nominal wage rates will also increase 1.7 percent annually.

The report says there are 655,000 employees in this sector and a further 521,000 in “provincially supported” organizations such as universities, childcare centres, children’s aid societies and LTC. This excludes municipal and federal government employees but encompasses the entire provincial broader public sector (BPS) – 1.176 million employees. This is about 18.5 percent of all employees in Ontario.

Broader Public Sector Employment Growth

To maintain services and meet government policy goals, the FAO suggests employment would need to grow by 2026-27 in the BPS group by 138,669 – 11.8 percent.

The FAO says there will need to be a growth of 56,974 employees by 2026-27 to maintain services in the “public sector.” This would be an increase of 8.7 percent for the 655,000 employees in hospitals, schools, colleges and provincial government. This 57,000 increase “is in addition to the immediate challenges caused by high job vacancy rates.”

This “public sector” group excludes 521,000 LTC, university, childcare, CAS and other BPS workers that the report refers to as “provincially supported.” Due to government program commitments in LTC, home care and childcare, the FAO says an additional 81,695 employees will have to be added to the 521,000 employees at provincially supported employers. This is an even higher increase than in the public sector – fully 15.7 percent.

The Cost of Wage Increases

Building on FAO figures, this BPS group has a total wage of $72 billion and a total wage and wage related compensation of $87 billion (assuming 21 percent for wage-related benefits). Every one percent increase in BPS wages therefore increases annual costs by $870 million. Compare this with the $31 billion increase in provincial revenues over the budget plan last year alone.

Hospital Employment Must Grow Faster

Notably, the FAO projects higher than average growth in the hospital sector: hospital employment will increase by 28,362 from 2021-22 to 2026-27 – or by 2.3 percent per year. That is an increase of 5,672 employees per year. This is based on the province’s plan to add 1,300 beds and the belief that that the employment to bed ratio will return to pre-pandemic levels by 2026-277. With the Ontario Hospital Association putting annual staff turnover at just under 15 percent, hospitals will have to hire about 45,000 staff per year, based on these figures, at least until they find a way to reduce turnover rates.

However, it is not so clear that this estimate will deal with reducing the currently very high level of hospital staff vacancies, or sufficiently deal with pressures arising from aging, population growth, COVID and long-COVID. I very much doubt it. It certainly will not deal with under-capacity – 1,300 beds is only about an increase of 4 percent over 5 years, which won’t even keep up with population growth.

Non-Union May Lose Out

The FAO costed the impact of Bill 124 (legislation limiting compensation increases to 1 percent) in the public sector and estimated that it will save the province a cumulative total of $9.7 billion in salaries and wages costs. If the Bill is overturned by the courts, however, the costs to the province may be significantly less. With no union to help them collectively push their interests, the FAO is rightly dubious that the 18 percent non-unionized public sector employees will get anything.

Do public sector workers have to accept lower wages? While the FAO reports suggest public sector workers (and, by extension, employees of “provincially supported” employers) face the threat of perhaps the greatest decrease in living standards for many decades, the report also suggests that they do have some leverage.

The report echoes popular concerns about health care staff shortages: “Vacancy rates, or the number of vacant jobs as a share of total jobs (occupied and vacant), have risen across most public and private sector job categories. In the Ontario Public Sector, this challenge is most pronounced in the health sector, where the vacancy rate has nearly doubled since 2019.”

When considering “risks” to its modest wage projections, the FAO flags staffing and vacancies in healthcare:

“Vacancy rates, or the number of vacant jobs as a share of total jobs (occupied and vacant), have risen across most public and private sector job categories, including for positions in the Ontario Public Sector and other provincially supported organizations. This suggests that the province will have difficulty staffing existing positions and hiring to meet new program commitments. This challenge is most pronounced in the health sector across all job categories. For example, in the second quarter of 2022, almost nine out of every 100 jobs were vacant in nursing and residential care, for a total of 16,315 vacancies, which was more than double the 4.0 percent vacancy rate from 2019. In other healthcare, which includes home care, clinics and doctors’ offices, there were 11,775 job vacancies in the second quarter of 2022, with a job vacancy rate of 5.5 percent, double the 2.7 percent job vacancy rate in 2019. Lastly, there were 16,020 job vacancies in hospitals in the second quarter of 2022. Since 2019, the hospitals’ job vacancy rate has increased from 3.4 percent to 5.8 percent.”

The FAO states, “the province may still need to increase wages beyond the assumptions in the FAO’s base case projection to ensure sufficient staffing to maintain existing public services and meet program expansion commitments.”

Get People’s Voice delivered to your door or inbox!

If you found this article useful, please consider subscribing to People’s Voice.