By Kimball Cariou

Throughout many decades of class struggle, socialists and other radicals have long understood the importance of providing assistance to working people. While our focus is on demanding adequate programs from the state – to the point that we advocate state power for the working class in order to guarantee sufficient support – we also support efforts to provide for the immediate wants of people in need.

But is this a strategy for achieving the fundamental change that working people need? Some elements of the political left are espousing just that, through an elevated focus on “mutual aid” and “serve the people” projects. However, a historical and class-based analysis of such approaches shows that while “mutual aid” can be a useful tactic when it is concretely tied to the struggles of working class and oppressed people, it too easily becomes derailed from a class struggle focus and deteriorates into a form of “left-branded” charity.

Shortly after noon on June 5, 1935 – three days after their historic journey began in Vancouver – the On-to-Ottawa Trekkers scrambled off a freight train at Golden, British Columbia, a railway and farming village in the Rocky Mountains. The previous day, Relief Camp Workers Union leader Arthur “Slim” Evans had sent a telegram from Kamloops to a local communist, giving their time of arrival and a simple request: “Please prepare food and welcome for one thousand.”

As related by Ronald Liversedge in Recollections of the On-to-Ottawa Trek, 1935, with just 24 hours of notice, the “little white-haired woman” contacted by Evans found supportive farmers to donate a huge supply of beef and vegetables and organized a volunteer crew to cook stew and bake bread for everyone. The memorable dinner gave a huge lift to the Trekkers in their struggle for “work and wages” before they were halted on July 1 by a violent police riot in Regina.

Despite that attack, the Trek did achieve its main objectives. A few months later, the Tory government of R.B. “Iron Heel” Bennett was defeated, the hated “25 cents a day” work camps were closed, and the labour movement was launching successful campaigns to win social reforms like unemployment insurance.

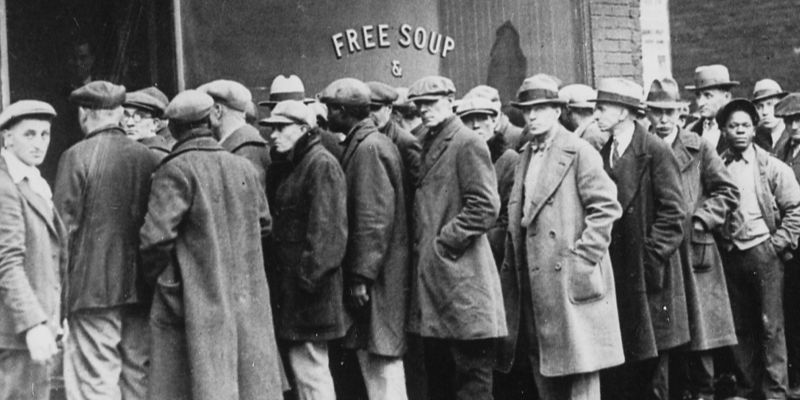

Fast forward to the early 1980s. As the last few dozen surviving Trekkers planned activities to mark the 50th anniversary of 1935, Canada was in the grip of a new capitalist recession. Unemployment and poverty skyrocketed, while the labour and anti-poverty movements called for improved unemployment insurance, massive job creation and other urgent measures. But at the same time, another “alternative” emerged: “temporary” food banks to help millions of people facing hunger.

Schooled by decades of class struggle, some Trek veterans warned that food banks might have a very different outcome. Neoliberalism was rapidly becoming the gospel for ruling classes across the capitalist world. Far from being scaled down when the recession ended, the Trekkers (and the Communist Party) warned that the food banks would become permanent as governments eagerly tried to shed any responsibility for social welfare policies.

Some dismissed these warnings as exaggerated. But food bank drives quickly became a fixture of Canadian society, a tool to help governments ignore demands for increased social assistance rates or higher minimum wages. What began as a noble experiment in human solidarity was almost instantly turned into a never-ending exercise in charity.

The concept soon expanded to other social problems. As governments squeeze public education spending for example, annual appeals are issued to donate towards the cost of classroom supplies. Sometimes these campaigns simply widen the gap between rich and poor. In Vancouver for example, fundraising campaigns in wealthier neighbourhoods allow “west side” schools to spend millions on the latest computers and other technology, while Parent Advisory Committees at “east side” schools raise a few hundred dollars at bake sales.

In essence, the last several decades have seen a steady erosion of income redistributive measures, while budgets cut taxes for upper-income earners and corporations. Governments are not “downsizing” as we sometimes hear because spending on police forces, the military and other repressive elements of the capitalist state has increased.

As the percentage of budgets allocated for low-income housing, social assistance and public education declines over time, the results include mass homelessness, growing hunger and poverty as well as limited access to crucial programs such as childcare and employment insurance.

More and more, working people are questioning the insanity of this process. Why do governments fail to tackle the social disparities that make life so difficult for the people who do all the work? Are the politicians blind, stupid or just corrupt?

Of course, some individual politicians do fall into those categories. But the real problem is that governments in capitalist societies such as Canada are an important part of a state apparatus which serves the interests of the ruling class. In the absence of mass struggles for progressive reforms, exerted by a powerful working-class movement, the natural tendency of governments at all levels is to enact policies which satisfy the demands of the rich and the big corporations. Sometimes popular anger erupts which forces governments to legislate reforms. But building militant mass struggles to achieve and defend such gains requires years of hard work, not to mention leadership by left forces such as the Communist Party.

When the political balance of forces is favourable to the ruling class, the pendulum swings the other way. Often this leads progressive-minded people to consider easier, quicker solutions under the umbrella term of “mutual aid.” Why not for example pool donations from some folks who have jobs in order to buy food for desperate community members? If food banks have become bureaucratized, why not bypass institutionalized barriers by simply finding locations where free food can be left for anyone to take?

It’s a tempting strategy at a time when governments seem impervious to popular demands. But is this a strategy for achieving the fundamental change that working people need? Some elements of the political left are espousing just that, through an elevated focus on “mutual aid” and “serve the people” projects. While “mutual aid” can be a useful tactic when it is concretely tied to the struggles of working class and oppressed people, the examples above and other experiences show the need for caution.

During the 1980s, one tactic of the left was to establish unemployed action centres at locations made available by unions or anti-poverty groups. These initiatives sometimes had temporary success in helping to mobilize around immediate demands. But the action centres often turned into de facto social agencies, burning out volunteers with limited time and inadequate training.

In today’s situation, the mutual aid strategy raises more fundamental questions. Given the huge numbers of jobless, under-housed and hungry people in Canada, is it possible to assist more than the tiniest sliver of those in need using these tactics? And if there is some success in helping people in a low-income neighbourhood, can this be maintained indefinitely? Perhaps more to the point, will the energy and resources devoted by groups using such “mutual aid” tactics detract from their ability to organize and mobilize for social reforms which could improve the lives of millions?

At a philosophical level, is this strategy a potential model for a very different approach to the mass poverty created by capitalism? To the extent that such projects succeed, are they simply a device for the working class to share the burden a bit less unequally, while letting governments redistribute wealth to the benefit of big business and millionaires?

These questions point to an important difference between solidarity and charity. Real working-class solidarity helps militant movements to maintain their efforts during moments of difficult struggle. That’s why communists and other radicals support picket lines, workers on strike or activists occupying government or corporate offices to back their demands. At the community level, it’s why we pass the hat to help neighbours facing eviction or the impact of a fire in their apartment.

But if we establish semi-permanent structures to redistribute our own wages among ourselves, do we risk creating new types of charities which can let the ruling class off the hook? It’s a dilemma which needs careful consideration including serious study of the history of strategies and tactics employed by the working-class movements of the past. And it’s also a dilemma which can’t be resolved simply by switching labels and calling something “solidarity” if it’s still really just charity.

Get People’s Voice delivered to your door or inbox!

If you found this article useful, please consider subscribing to People’s Voice.

We are 100% reader-supported, with no corporate or government funding.