By Owen Schalk

nearly ten years later

look at me here analysing

still distraught and debating

sympathising synthesising

regretting and remembering

and time

just passing

“Nearly Ten Years Later (For Grenada)” by Merle Collins

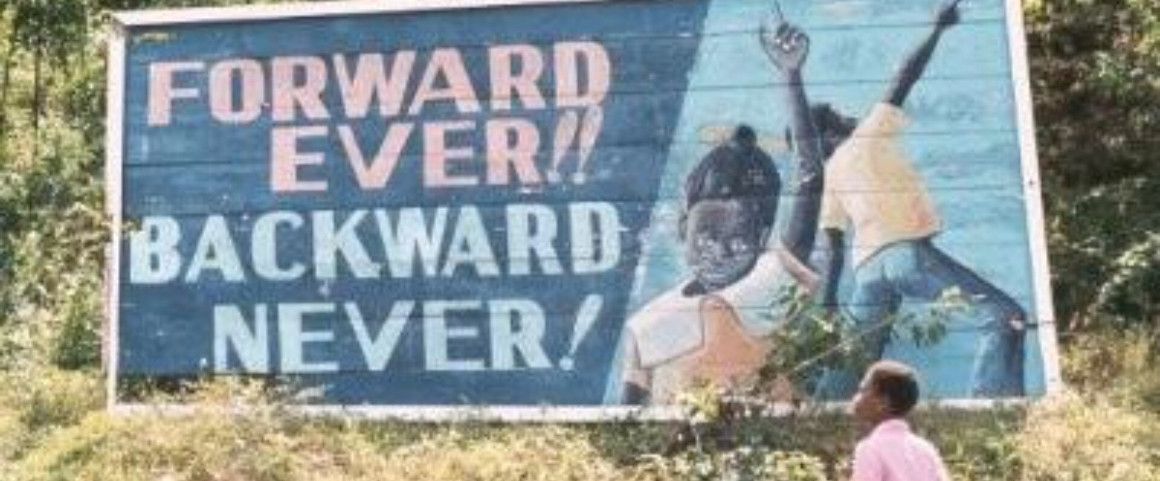

October 16 marks 38 years since the death of Maurice Bishop, leader of the tragically short-lived People’s Revolutionary Government of Grenada (PRG). The PRG was formed when the New Jewel Movement (NJM), led by the widely popular Bishop, seized control of the country from the US-backed dictator Eric Gairy. Although the NJM government lasted only four years before Bishop was killed in a military coup led by Bernard Coard (after which America invaded to destroy the remnants of the movement), Bishop’s humane and popular policies, as well as his internationalist perspective, remain an inspiration to students of the Grenadian Revolution.

Grenada is a small island in the southern Caribbean, near the cost of Venezuela. Prior to the colonization of the Americas, it was populated by the Indigenous Arawaks and the Kalinago, or Caribs, the people from whom the Caribbean gets its name. The island was eventually colonized by the French, who killed most of its Indigenous population, but it was taken by the British at the end of the Seven Years’ War, which explains why English is the most common language in Grenada today. In a pattern replicated across the Americas, the British forcibly relocated thousands of enslaved Africans to the island and used their labor to produce profits for the metropole. As a result, the vast majority of Grenadians claim African ancestry.

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, many Grenadians lost work. This caused them to seek employment abroad, which often led to involvement in trade unionism and anti-colonial activism. One of the most important activists at this time was Eric Gairy, who returned to lead his country out of the colonial period in 1974. Once in power, however, he became a brutal dictator who received considerable support from the US and its allies. Gairy terrorized the population with his Mongoose Gang, a private militia that targeted critics of the regime for torture and death (including Rupert Bishop, the father of Maurice Bishop, who was killed in 1974) and received arms and training from Pinochet’s Chile. In exchange for his loyalty, he was granted membership to the English Privy Council in 1977, and later that year he was knighted by Queen Elizabeth.

Unsurprisingly, Gairy and his clique showed little interest in the economic development of Grenada. Agricultural production dropped, unemployment rose, prices skyrocketed and movements against his government gained more and more influence. The NJM, a communist group modelled on the tenets of Marxism-Leninism, became the primary body for collecting and organizing anti-Gairy resistance. Gairy was aware of the NJM’s goals, and in 1979 he planned to have its leaders murdered while he was away on a trip to the United States. The NJM learned of his plot and acted first, detaining the Mongoose Gang and seizing control of the state. On March 13, 1979, with the resounding support of the population, they declared the founding of the People’s Revolutionary Government of Grenada. Maurice Bishop became prime minister.

Bishop was a well-travelled Marxist with an internationalist philosophy, and he spoke positively about anti-imperialist intellectuals like Frantz Fanon, post-colonial leaders including Fidel Castro, Che Guevara and Julius Nyerere, and figures of American resistance such as Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. Under his premiership, healthcare became a human right, low-income housing was established for the first time, food production soared and adult illiteracy was reduced to less than 5 percent in three years. Furthermore, the National Women’s Organization of Grenada (NWO) was established with the intention of prioritizing gender equality. Trinidadian scholar Rhoda Reddock declares that “the leadership of the Grenada Revolution was unmatched in its public acknowledgement of women’s role in bringing about the revolution and extended an invitation to them to participate in the ‘process of revolutionary transformation.’” All of these initiatives were undertaken in a popular, participatory fashion, and they resulted in significant social and infrastructural gains. The successes of their communist governance model made the PRG an enemy of the United States.

After his normalization efforts with America collapsed, Bishop recognized that he had become a target. As he outlined during a speech at Hunter College in New York City on June 5, 1983:

“They give all kinds of reasons and excuses [for opposing us] – some of them credible, some utter rubbish. We saw an interesting one recently in a secret report to the State Department…That secret report made this point: that the Grenada revolution is in one sense even worse – I’m using their language – than the Cuban and Nicaraguan revolutions because the people of Grenada and the leadership of Grenada speak English, and therefore can communicate directly with the people of the United States…They [also] said that 95 percent of our population is Black…if we have 95 percent of predominantly African origin in our country, then we can have a dangerous appeal to 30 million Black people in the United States.”

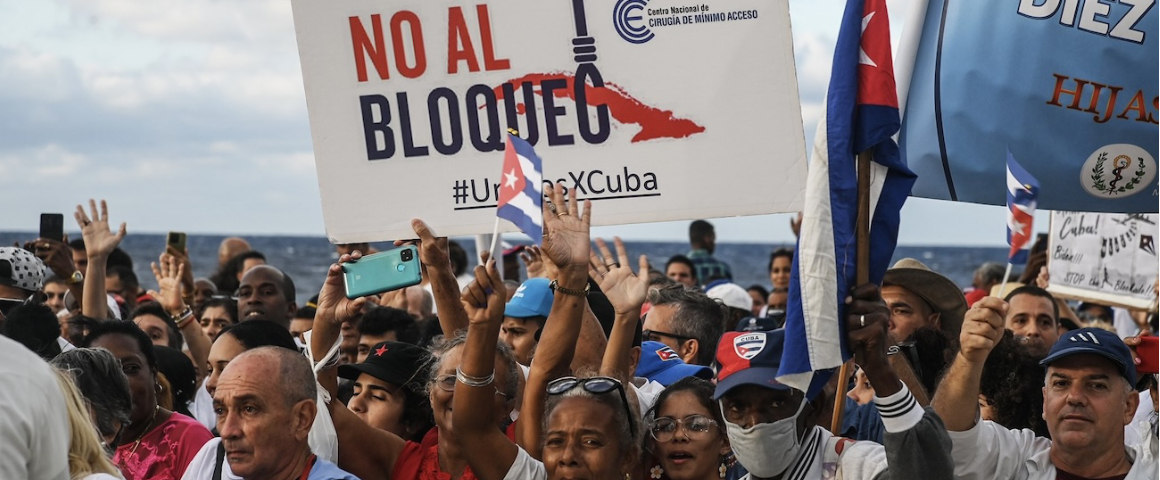

Both Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan looked for ways to demonize and destabilize the Grenadian government – Reagan even called an airstrip built to support tourism, the second largest sector of the island’s economy, a “Cuban-Soviet power projection” – and the American media played along. As Noam Chomsky writes in Necessary Illusions, “US actions…to undermine the government of Maurice Bishop were barely reported…Also unreported were the other measures pursued [ex. the blocking of aid to Grenada after the August 1980 hurricane] to abort progress and development under a government now conceded to have been popular and relatively successful.”

When Bernard Coard, the PRG’s Deputy Prime Minister, seized power in a coup whose exact circumstances remain muddled to this day, Bishop was imprisoned and ultimately executed. The Reagan administration seized this opportunity to finish off the New Jewel Movement once and for all. Over 7000 US troops invaded on the pretext of protecting US students on the island, but it soon became clear that their true intention was to prevent the revolution from holding onto power. As Lola Campos writes, “[the American invasion] resulted in the reinstitution of the former Grenadian constitution and an immediate reversal of the accomplishments of the NJM’s revolution.”

Over forty years later, students of the violently interrupted Grenadian Revolution are – to borrow the words of poet Merle Collins, an ardent supporter of the NJM – “analysing / still distraught and debating / sympathising synthesising / regretting and remembering” the circumstances that brought Maurice Bishop to power and those which resulted in his ouster. Although the PRG is no more, the social and economic accomplishments of the New Jewel Movement, in addition to its internationalist focus, remain an inspiration to those seeking to imagine a new North-South relationship outside the bonds of global neocolonialism.

[hr gap=”10″]

Get People’s Voice delivered to your door or inbox!

If you found this article useful, please consider subscribing to People’s Voice.

We are 100% reader-supported, with no corporate or government funding.