By Sonya Stepanova

This year is the 100th anniversary of the invention of insulin by Frederick Banting at the University of Toronto. The world celebrates his transformative discovery, but a closer look at the situation with insulin – both in this country and globally – reveals that it is in a state of crisis. This should raise more questions than cheers.

The pandemic has brought attention to a lot of issues with healthcare and there is a real opportunity to organize around reforms that people have been promoting for years. The COVID-19 pandemic has shone a light on the pharmaceutical industry, and insulin is a good lens to use when examining Big Pharma.

Around 300,000 people in Canada and between 19-38 million people worldwide have Type 1 diabetes, an incurable illness that requires multiple daily insulin injections. Insulin is a hormone people need to regulate their blood sugar – without it, a person could not survive for longer than a week.

Today, for every two living people with Type 1 diabetes, there is another one who has died. This is an appalling statistic considering the fact that we have the medicine and technology that could not only prevent those deaths, but also allow people with diabetes to live for as long as those without it. The challenge lies in actually making sure people can access what they need.

The first issue, and the one that gets the most attention, is that of affordability. Insulin is the sixth most expensive liquid in the world. This high cost forces people to ration their insulin, which severely impacts their health. One study found that in the US and Canada, as this cost increases, so does the frequency of diabetes-related amputations. Furthermore, research has shown that while Canada has seen a decrease in diabetes-related deaths since 1994, the decrease among people in the lowest income group was significantly smaller than those in the highest income group.

The cost of insulin in Canada is about $40 per vial, which is inexpensive compared to insulin prices in the US, but still outrageous. Insulin costs about $3-$6 to produce and is provided free of charge in many countries including Europe, Britain, Russia, Morocco, Kuwait, Kyrgyzstan, Laos, Lebanon, Mauritius, Mexico, Nicaragua and Vietnam.

In addition to affordability, vulnerability of supply is a huge issue. While Canada proudly celebrates that it is the country in which insulin was invented, there hasn’t actually been any insulin production here since the late 1980s and the country currently relies completely on imported medicine. The COVID pandemic has drawn attention to the problems of not having domestic vaccine production, but healthcare advocates have been warning about these dangers for years.

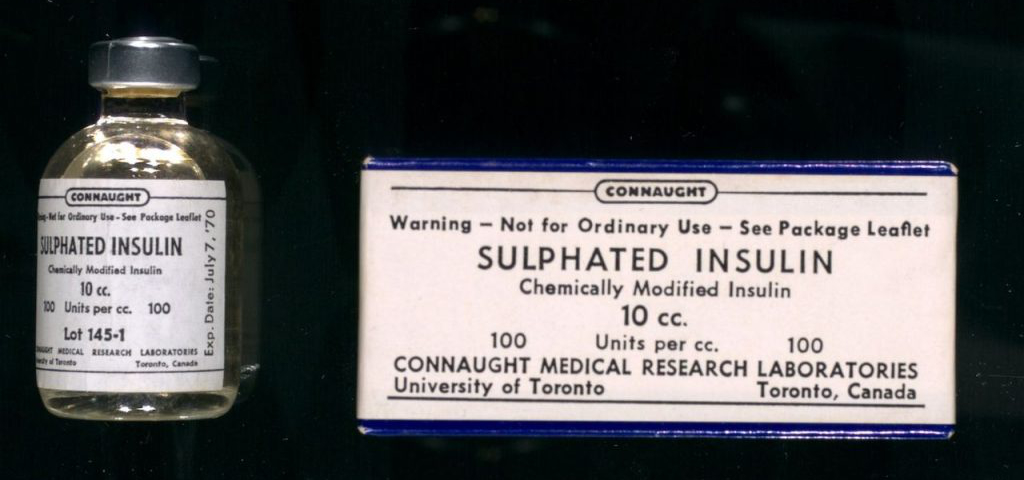

For over 70 years, Connaught Laboratories was a non-commercial publicly owned drug manufacturer, until the Conservative government of Brian Mulroney privatized it in 1986 (although the Liberal government of Pierre Trudeau had planted the seeds of Connaught’s privatization in the 1970s). In the years since, with the additional factors of deregulation of the pharmaceutical industry and the NAFTA free trade deal, Canada’s spending on healthcare has decreased while spending on drugs has skyrocketed. Underfunding and divestment from hospitals and primary care has been accompanied by a growing emphasis on solely drug-based solutions for many illnesses. This demonstrates the extent of Big Pharma’s influence on policymakers.

A third major issue with insulin is its safety. Insulin has a very low safety profile and is the second most dangerous drug in terms of causing accidental deaths. In the 1990s, pharmaceutical manufacturers all began to synthesize insulin from chemicals rather than from animal glands. This new “analog” insulin is much more profitable for pharmaceutical companies. It was instantly marketed as a better option for all patients, despite the fact that there is actually little science to support this claim. Patients were switched to this new insulin without their consent, and some had tragic reactions – in Canada, 11 people died and hundreds of people became permanently disabled because of allergic reactions. It was only after a class action lawsuit that animal insulin was brought back into the Canadian market, but even now advocates have to fight to ensure that it is available.

A common capitalist framework for analyzing healthcare is to view it as a stool with three legs – the private sector, government and civil society. The argument is that all three legs must work together in order for the stool to stand. The same framework can be used to critique the insulin crisis.

Most of the issues contributing to the insulin crisis are the result of private sector involvement. Just three companies – US-based Eli Lilly, Danish firm Novo Nordisk and the French company Sanofi – control 99 percent of the market in terms of profits and 96 percent in terms of volume. A recent analysis showed that 70 percent of countries got insulin from one of these Big 3, 28 percent bought it from local manufacturers who only sell to the country in which they are based, and 16 percent purchased none at all. In countries without insulin, all of which are located in the Global South, the life expectancy of a person with diabetes is less than a year, just as it was here a century ago. The Big 3 have been sued for collusion and price gouging – insulin is priced between 2.5 and 4.5 times higher than any other non-communicable disease treatment regimen.

Frederick Banting declared that insulin was a gift to the world, and famously sold the patent for only $1. Big Pharma intervened almost right away. A 1923 letter from Eli Lilly head JK Lilly, available at the Insulin Collection at the U of T Library, outlines a plan to have only a small number of companies control the drug’s production and distribution. Currently, insulin is no longer under patent, but the large corporations have retained control by patenting the different technologies for administering it (insulin pens, for example).

Big Pharma’s dominance is enhanced by the fact that there is no generic version of the drug. In part this is due to the fact that, while insulin is inexpensive to produce, the requirements for its manufacture and testing are very strict, making it less appealing for generic drug companies.

This situation – monopoly control over a commodity that is essential to millions of people who have no choice but to pay for it or die – leads to a critique of the second leg of the stool, government.

Combined government policies of privatizing Connaught and deregulating the pharmaceutical manufacturing industry (particularly through extending patents) have left the country in the position of relying on and negotiating with private for-profit drug corporations. Insulin is a perfect example of how these policies benefit corporations at the expense of people’s needs.

Even within the profit-driven confines of capitalism, there are short term options that would help alleviate the insulin crisis. For example, the Canadian government could start purchasing drugs in bulk through direct negotiation with manufacturers, rather than working through private insurance companies. Britain takes this approach and has allowed the government to set a limit on how much it is willing to spend on the drug, to which the company either agrees or loses the market entirely.

However, such approaches will be severely limited and temporary without a publicly owned non-commercial pharmaceutical manufacturer. Clearly, nationalizing the pharmaceutical industry as a component of universal pharmacare is a critical demand and one around which the working class and its allies must mobilize.

And this highlights the third leg of the healthcare stool, “civil society” or more precisely the non-government and non-business advocacy organizations.

The role of advocacy groups should not be underestimated – during the AIDS crisis, for example, many of them played a critical role in fighting stigma and securing funding and services. However, in the case of insulin (and pharmaceuticals in general) non-profits often serve a much more sinister function.

Currently, a common pattern is for patient advocacy groups to take money directly from the pharmaceutical industry. This is a good deal for both sides: the organization gets funding, and the pharmaceutical company gets advertising. One Eli Lilly executive explicitly described educational videos and customer quizzes from patient advocacy groups as excellent marketing tools, saying that the company offers “an information product wrapped around a pharmaceutical product.” Indeed, some of the biggest corporate sponsors of Diabetes Canada are manufacturers of diabetes medicines: Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly, AstraZeneca, Abbott and others.

Most of the time, these nonprofits are the only groups that get a seat at the table when legislation is being prepared, and their connection with corporations affects that. For example, in 1997 the Canadian Diabetes Association (CDA) surveyed its members about their experience when switching to analog insulin. They found that 43 percent said the switch was not easy and that they would switch back to animal insulin if they could. What did the CDA do with this information? Nothing.

Another example is the Act to establish a national framework for diabetes (Bill C-237), a private member bill sponsored by Liberal MP Sonia Sidhu and passed by the government this July. Rather than mandate action to improve access and affordability, the legislation focuses on education, date collection, “knowledge sharing” and small adjustments to the administration of the disability tax credit. In developing this very corporate-friendly package, Sidhu did not meet with a single patient-led advocacy group (despite requests to do so from groups such as T1D International, a global leader in the Insulin4All movement) and instead worked with corporate-funded Diabetes Canada.

This problem of corporate-backed advocacy groups is even more egregious in the US, where there have been cases of such “diabetes organizations” working to block legislation that would make insulin more affordable.

An examination of the insulin crisis and the role of Big Pharma sheds light on how the industry operates in general – many parallels can and should be drawn with other drugs and illnesses.

Looking at this situation in the context of the COVID pandemic hardly inspires optimism. The federal budget tabled in April was predictably disappointing, with regurgitations of previous promises for pharmacare, country-wide standards for long-term care and improved funding for healthcare, but no action or progress on any of them.

The one health reform that the government has introduced is Bill C7, on medical assistance in dying (MAID). Among progressive people and organizations there are different views about MAID, but it should set off alarm bells for everyone that the biggest healthcare reform in many years is not about dignity in life – through pharmacare, a nationalized drug manufacturing industry and investing in actual healthcare including support for people with disabilities – but, rather, dignity in dying.

Dr. Norman Bethune, pioneer of socialized medicine and member of the Communist Party of Canada, argued that healthcare needed to be approached holistically. Patients can’t just be looked at as individual units; and their illnesses must be viewed within the context of their society. Although diabetes can affect anyone, people’s experience of it is vastly different based on their location in the world and their class. It is a prime example of what happens when patients are simply a source for increasing profits.

And it is another indication that, while immediate reforms are important and urgent, we ultimately need to move past capitalism if we are to truly secure good healthcare.

[hr gap=”10″]

Get People’s Voice delivered to your door or inbox!

If you found this article useful, please consider subscribing to People’s Voice.

We are 100% reader-supported, with no corporate or government funding.