In 2017, after 16 years of vicious attacks on public education, teachers, parents and students welcomed the defeat of the right-wing Liberals. But the positive mood of public education supporters has gradually waned under the NDP government of John Horgan.

The NDP did act on the Supreme Court ruling which ordered the province to restore funding cuts imposed by the Liberals, but little more. Teacher salaries remain the lowest in western Canada as the latest round of collective bargaining continues, making it difficult for some school boards to fill positions in cities with sky-high living costs such as Vancouver.

Nor has the NDP halted the Liberal policy of spending millions to support private and religious schools, at the expense of the public system.

One of the most controversial moves by the NDP has been what the BC Teachers’ Federation calls a “misguided proposal to change the way services for students with special needs are funded. The proposal, called the prevalence model, would move funding away from the actual needs of students to an impersonal statistical model that will put services to kids at risk.”

Former Vancouver School Board chair Patti Bacchus wrote this in a Georgia Straight commentary last November: “In its 2017 election platform, the B.C. NDP promised to review how schools are funded. Shortly after the election, Premier John Horgan tasked his education minister, Rob Fleming, with developing a stable and sustainable way to fund the kindergarten-to-Grade 12 education system. Good idea, and to the government’s credit, it’s working on it. That’s the good news.

“Here’s the other kind of news. From the outset, unfortunately, the review process has appeared to have serious flaws. For starters, Fleming appointed a review panel of senior bureaucrats to conduct a funding-formula review but didn’t include any representation from the BCTF, the B.C. School Trustees Association, or parent groups on the panel. Although senior bureaucrats have vast knowledge and experience, they tend to get to where they are by not rocking any boats or telling those in power things they don’t want to hear…

“The review ignored the biggest issue of all: there isn’t enough money to go around. Full stop. Spending months trying to figure out how to reslice a too-small pie will only create winners and losers. Instead, they should have done a review to determine what it would actually cost to provide optimal learning conditions and opportunities for all students.”

She quotes former BCTF president Glen Hansman warning that copying Ontario’s adoption of the so-called “prevalence model” to fund special needs education will mean fewer services and more rationing of scarce resources: “The final report was written from the perspective of senior managers who want to see accounting efficiencies, not from the perspective of teachers and support staff who actually work with these students. Simplicity and efficiency for government may sound like a lofty goal, but the cost will be significant disruptions to teachers, students, and parents.”

Hansman feared the main “prevalence model” would increase inequities between students and strip services away from the most vulnerable children.

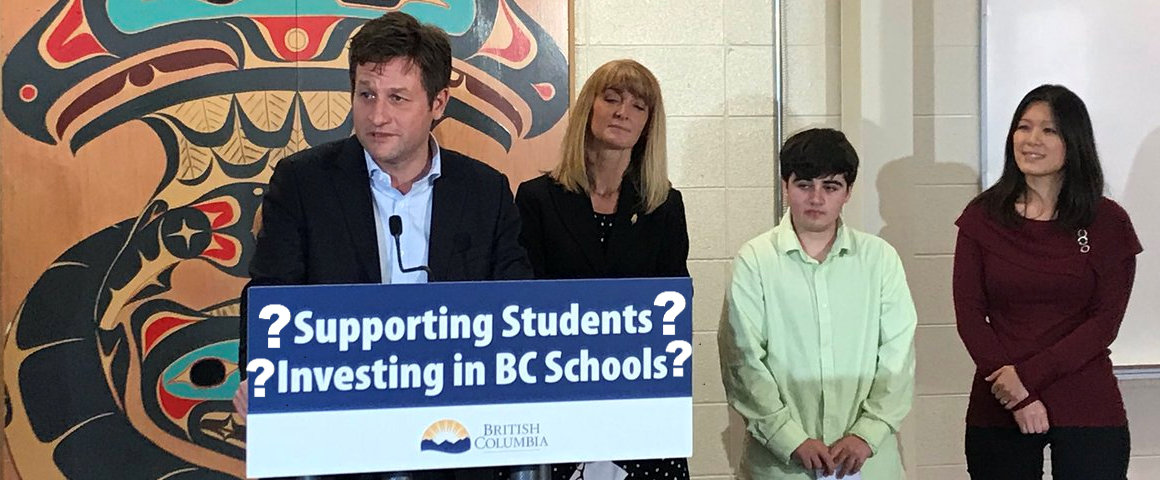

Fleming put it this way. “A number of districts suggested moving to a prevalence model based on the incidence of special needs in the population as an alternative to the current assessment and reporting-driven funding model… all agreed that this approach would reduce the administrative burden and provide districts with more time and resources to deliver services to students.”

“The prevalence model will lead to fewer special needs assessments and diagnoses,” responded Hansman. “Without that information, teachers will lose valuable insights at the start of each year when they begin working with a new class. If there is no record of diagnosis and paperwork articulating the nature of a student’s disability or learning challenges, teachers will not be able to properly address that child’s needs as they move through different grades. This disconnection in the name of accounting efficiencies will hamstring teachers’ efforts to support all students.

“Moving to a prevalence model will also force parents to fight even harder for specialized supports and services. Families who can afford it will turn to outside psychologists to diagnose their children’s needs. But kids whose parents can’t afford it, or don’t have a parent pushing hard in the principal’s office, will be left behind.”

At their recent AGM in Victoria, BCTF delegates almost unanimously adopted a resolution calling on the province to: terminate consideration of a prevalence model for special education funding; reform the provincial funding formula for operating grants to one based on the identified needs of school districts, an equitable distribution of resources, as well as the full mandate of the public education system; align special education funding with special education needs by closing the current gap between what school districts receive in special education funding and the much greater amount spent; dedicate funding for early identification and designations of students with special needs and for in-service for teachers; and move ahead with significant enhancements to operational funding for K-12 beyond the funding increases associated with enrolment growth.”

As the Communist Party of BC said after Premier Horgan took office in the summer of 2017, the key roadblock to carrying out the more progressive parts of the NDP’s platform is the refusal to even consider reversing the massive tax breaks granted in 2002 by Gordon Campbell. Since then, these gifts to upper-income earners and corporations have totalled an estimated $50 billion, depriving the BC treasury of about $3 billion annually.

The longer the NDP adheres to the neoliberal model imposed by the former government, the worse is the cumulative impact of this enormous revenue shortfall. Teachers, non-enrolling school staff, students and their families will pay an ever more onerous cost, while Education Minister Fleming sticks to this reactionary approach.