Doug Ford’s Conservatives have won a majority in Ontario. And the majority has to win Ontario back.

The June 7 provincial election was fought around two main messages. On the one hand was the approach that the election was a referendum on the McGuinty-Wynne Liberals, and out of that came the feeling that there simply needed to be a change. Never mind the politics. Never mind the shape or the content of that change. We just needed to replace Kathleen Wynne. That shallow de-politicized narrative was the one bit of wind always in Doug Ford’s sails, as the Conservatives consistently led projections for an electoral victory. That the Tories didn’t even have a platform until the last week of the campaign indicates the degree to which they were able to rely on this simplistic message.

But, to the extent that the election did become politicized, the other main message emerged. The battle lines were clearly drawn around issues of defending and extending working class gains in Ontario. These include maintaining the $15 minimum wage and related workplace reforms, expanding access to abortion services, increasing funding for public services like health care and transit, and implementing tax reform that puts the burden back onto corporations. The politicization that occurred was overwhelmingly the result of working class mobilization during the campaign. It involved not just trade unions but the entire working class – poor and unemployed people, women, LGBTQ, Indigenous people, immigrant and racialized communities, youth and students, people with disabilities, tenants, and many others. This effort to expose the nature and character of Doug Ford’s Conservatives, to reveal the dangers of a Ford victory, to project alternatives that are based on the needs of the working class, turned what appeared in April to be a coronation into an actual fight around class issues in the province.

Was it sufficient? Clearly not. Ford was consistently projected to win a majority and the electoral outcome reflected that. But saying that the working class mobilization was insufficient doesn’t mean that it wasn’t worthwhile and, in fact, necessary for building the resistance to the new government.

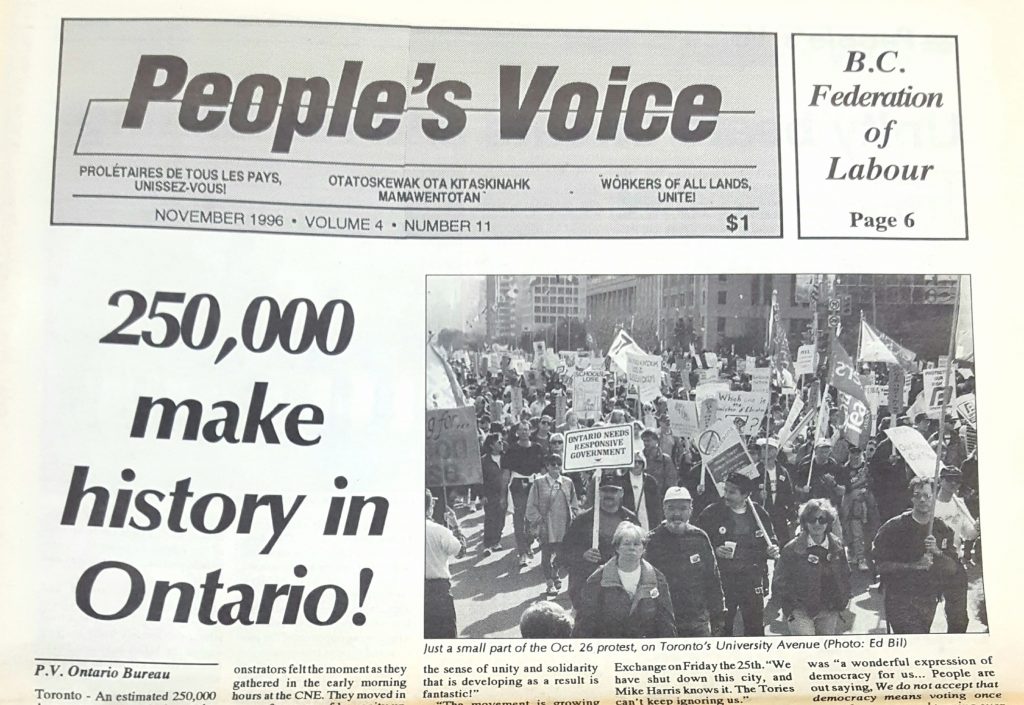

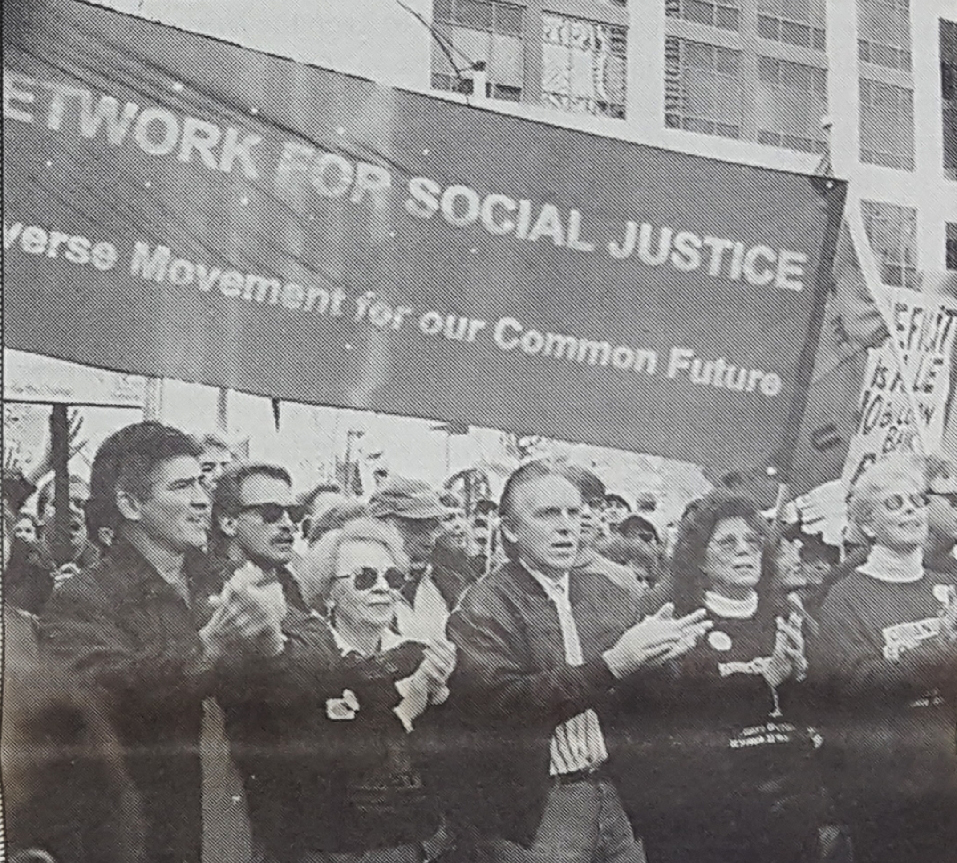

Thinking about building resistance inevitably leads to comparisons with the election of the Mike Harris Conservatives in 1995, and the widespread opposition movement that followed. There are obvious similarities: a Conservative government using a populist style to peddle a hard-right agenda that includes tax cuts for corporations and the rich, massive privatization, blatant disregard for Indigenous rights and the environment, attacks on low-income and poor workers, demonization of the public sector, and conservative social policies. Like Harris, Ford has declared that he will move quickly to implement his neoliberal and austerity policies, in order to pre-empt any opposition movement.

However, there are also several key differences between the current situation and that of 1995, and these factors will influence the development and direction of the fightback.

For starters, in the current conditions a hard-right government is more dangerous than during the mid-1990s. For the past two decades, harsh neoliberal and austerity policies have been implemented at the provincial, federal, and international levels. This has left services like healthcare, social assistance, public education and housing enormously weakened and much more vulnerable – sometimes critically so. As the Ontario Coalition Against Poverty (OCAP) noted just after the election, “Frankly, there is very little flesh for Ford’s knife to cut into. It will be going into the bone.”

Another key difference is the state of the trade union movement. On the one hand, trade unions are generally weaker now than during the 1990s, in part reflecting the massive loss of manufacturing jobs and two decades of attacks on the public sector.

Some of the unions that were key to building and leading the resistance to Mike Harris are not currently in a position – either politically or organizationally, or both – to play the same role today. At the same time, however, the Ontario labour movement has just emerged from a sustained campaign, in which it was largely united, to win a $15 minimum wage and workplace reforms. During the election campaign, the trade unions were also generally united in action to defend those gains. This unity in action is uneven and not as strong as it needs to be, but it contrasts with the divisions that plagued the trade union movement at the end of the Ontario NDP government and which continued into the fight against Harris.

One of the pillars of the 1990s fightback was the provincial network of local social justice coalitions. Working with local labour organizations, these groups were important for broadening the reach of anti-Harris mobilizing. Very few of these coalitions exist now, and where they do, they are smaller and often more narrowly focused on tactics of lobbying instead of movement building. However, other progressive movements have arisen. Idle No More, Black Lives Matter, Occupy, and Fight for $15 and Fairness all represent political efforts that have applied militancy, audacity and tactical creativity to achieve tremendous impacts in a relatively short period of time.

A fourth notable difference emerges from the election itself. The 1995 campaign was fought in the context of an unpopular NDP government, one that was attacked and undermined by corporate Ontario, and that had frustrated much of its working class support base. The main question was which of the two right-wing parties would replace the NDP, and so much of the public discourse was comparing right-wing policies. This time, it was clear that the Liberals would be replaced by either a hard right Tory party or an NDP that had moved nominally toward the left. Placed in the broader context of working class mobilization, the net result was that issues like public childcare, expanded healthcare, and free tuition actually formed a large part of the public debate. More and more people have now been actively engaged in questions of not only defending, but actively expanding working class gains.

Already, people have begun to move into motion to build the resistance to Doug Ford. OCAP has initiated meetings of organizations who are committed to building a movement that can disrupt and block the Tory agenda. The trade union movement and $15 & Fairness are mobilizing for a large rally on June 16, to defend the minimum wage increase. A coalition of groups is organizing a People’s Rally on June 30, calling for defense and expansion of public services and equity.

All the ingredients for a strong fightback exist. But they are different than in 1995, so the recipe needs to change. While elections in capitalist society are limited exercises, they are important in that the outcomes shape much of the parameters for our immediate struggles. What is decisive, however, is the “extra-parliamentary” fight – the mass movements in workplaces, schools and communities, that can apply the social and economic pressure necessary to block Ford’s political agenda. In the process, this movement can re-shape the parameters for ongoing working class struggles.

Dave McKee is the leader of the Communist Party-Ontario, which ran candidates in a dozen ridings across the province.