FREDERICTON – On April 1 the minimum wage in New Brunswick will be raised to $11.25 an hour – a 2 percent increase, just enough to keep abreast of inflation. From now on, says the NB government, this policy will continue. Indexing of the province’s wage floor to the consumer price index (CPI) will be the new norm, so that workers will know exactly what they’re getting, regardless of inflation.

While the legislators (whose average salary is $104,000 a year) present this as sheltering the province’s working poor beneath their benevolent and protective wings, some of the working poor themselves have doubts.

Fight for Fifteen Fredericton was formed in the province’s capital in 2017. It is made up of workers and students, many of whom found that the $11.00 hourly they were receiving just didn’t pay the bills. They decided that a public exposure of some economic realities and a polite – or reasonably polite – request for a living wage might be in order. To them, the province’s new wage policy isn’t so much a gift as a bucket of cold water over the head.

Abram Lutes, one of the group’s co-chairs, says the current minimum wage in New Brunswick “is not a living wage…. fifteen dollars an hour would be much closer to that.”

Another group spokesperson adds that “currently, New Brunswick has the worst poverty rates in the country, where nearly one in six children in this province are growing up in poverty. This is a crisis. Raising the minimum wage to a livable wage is a key to fixing this unacceptable situation.”

A Facebook post by one of the students in the group has this to say about indexing the minimum wage to the CPI: “Indexing it to CPI at such a low rate basically just keeps it low… forever.”

If anything, he understates the problem. In real (inflation adjusted) terms, the province’s minimum wage is about the same as it was 40 years ago. Expressed in today’s dollar, it was $10.90 in 1977. So with her weekly cheque today’s worker can buy about the same quantity of goods and services as her grandmother could in her day.

Looked at from one point of view, this is parity: nobody’s losing out; everybody’s getting by. But the other part of the picture is labour productivity.

Our grandparents went off each morning to computerless workplaces. Their machinery didn’t have microprocessors in it; on the water there were crude fishfinders and no GPS; forestry was less mechanised. The result was that in an hour’s work they only produced about half the output of today’s worker. Expressed in today’s dollars, gross domestic product (GDP) per capita in New Brunswick was $21,000 in 1977. Now it is $45,000.

Viewed in light of this economic growth, the static wage level doesn’t seem quite so fair. Society in total has become much wealthier. But not the workers.

It isn’t that New Brunswick is exceptional in this regard, some fishy economic mutant on the eastern fringe of the country. Nationally, the picture is the same.

In 2016 a U of T economist, James Uguccioni, put out a paper entitled “Explaining the Gap between Productivity and Median Wage Growth in Canada, 1976-2014”.

Here’s what it said: over the period 1976-2014, labour productivity – the amount of stuff produced by the average worker in an hour’s work – went up 52.5 percent. Meanwhile, the median hourly wage went up only 3.3 percent.

Uguccioni found that this exploding wage-productivity disconnect reflected itself most clearly in two ways: 1) increasing income inequality; 2) the decreasing share of the national product that is returned to labour as wages.

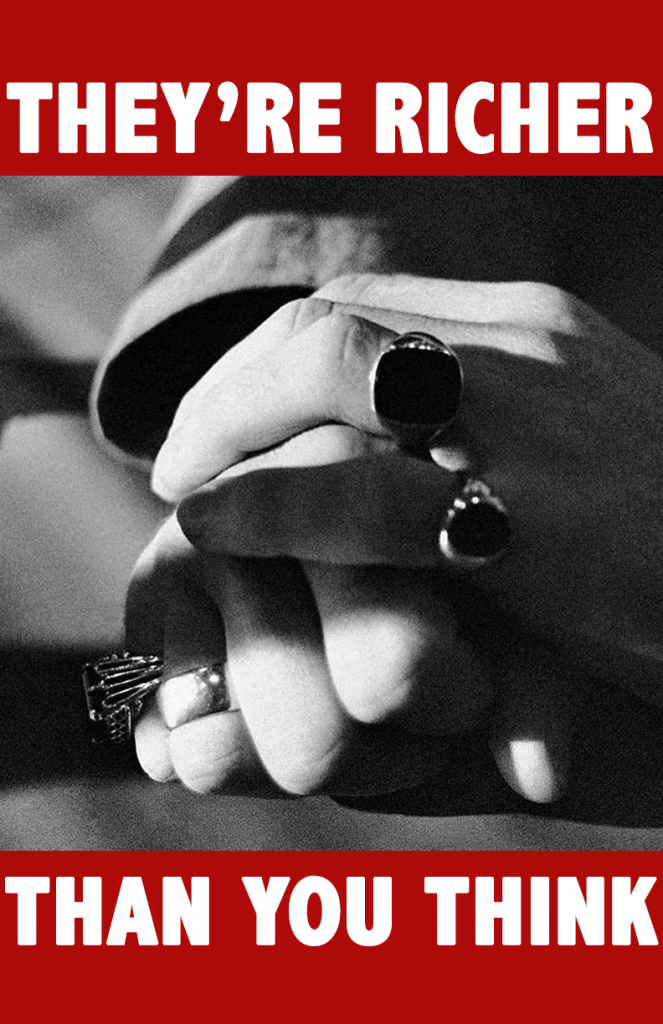

Concerning income inequality, it is no secret that this has increased in recent decades. Less well known is how concentrated the gains have been at the very top of the income spectrum – not so much among the famous “One Percent” as among the top 0.1 percent. According to figures in a 2013 paper by UBC economist Kevin Milligan, those babes of the boardrooms managed to double their real incomes over the quarter century 1980-2005. Incomes of the top one percent rose by 25 to 45 percent according to various measures. It is hard to imagine all the curses these folks would pile upon any legislature that ventured to index *their* incomes to the CPI.

The large income gains which Canada’s wealthiest people have enjoyed during the last several decades are connected to a simultaneous boom in the fortunes and power of the country’s top 50-100 corporations – to which many of these people are of course linked by executive position or ownership.

The picture is one of centralisation of the country’s capital over the last 40 years into a small number of very large companies.

A comparison of the TSX 60 – the 60 biggest companies on the Toronto Stock Exchange – to the rest of the 1500 companies on the exchange illustrates the centralising trend. The following figures are from a 2012 paper by Jordan Brennan for the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives:

In the mid-1970s, the top 60 firms had about 15 percent of the total capital value (equity) on the TSX. Now they have 60 percent.

In the mid-1970s their net profit was about 25 percent of all profit realised by firms on the TSX. Now it is 60 percent.

Their capital value, expressed as a percentage of Canada’s GDP, has gone from about 17 percent in the mid 1970s to 69 percent now.

In Brennan’s words, “This is a staggering degree of corporate concentration. When we speak about Canadian business or the corporate sector, we are effectively referring to 60 firms that dominate the Canadian political economy…. The equity market is effectively made up of these 60 firms. Many important decisions made in the Canadian political economy are conditioned by their performance and their values.”

The blooming of these monstrous firms of course corresponds to a withering of the rest. It has been a difficult 40 years for “mom and pop on main street” businesses. And it has been a difficult 40 years for labour, as this new corporate elite has used its concentrated political-economic power to shift government policies, beat back unionisation rates, and put a clamp on wages – all the while calling for the vast majority of the country to submit to principles of economic “austerity” which it clearly does not apply to itself.