The Horgan NDP government’s first full annual budget was presented on February 20. As widely expected, Finance Minister Carole James announced some worthwhile initiatives, while falling well short of the changes desperately needed by poor and working class families.

One area which received wide attention is child care, a key issue in last year’s provincial election when the NDP promised to implement a $10/day plan. That pledge remains to be carried out, but child care advocates welcomed some steps in the right direction.

The budget allocates $1 billion over three years towards child care. It proposes to create 22,000 new spaces across the province, and to expand the Head Start program for indigenous families both on and off reserve. It reduces fees by up to $350/month, targetted to benefit up to 50,000 families. Many others will receive “affordable child care benefits” of up to $1,250 for families with pre-tax incomes of $45,000 or less. The budget also increases spaces to train Early Childhood Educators, but does not immediately raise wages of child care workers, a relatively low-paid and almost entirely female section of the workforce.

In response, the $10 a Day Child Care Campaign thanked its supporters and allies who have campaigned for years to “fix BC’s child care chaos,” and congratulated the government for finally taking action.

Senior economist Iglika Ivanova of the BC Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA), “This help children get off to a good start, more mothers will be able to work and new jobs will be created, which will boost the economy and increase tax revenues almost immediately.”

The CCPA also welcomed the new 30-point provincial housing plan, and elimination of the regressive Medical Service Plan premiums.

A total of $1.6 billion will be invested into housing over three years, and $6.5 billion over 10 years for 114,000 homes. In the first three year period, 19,000 affordable rental units will be built for families with moderate incomes, but “affordable” and “moderate” are words with very elastic definitions when it comes to the housing market in British Columbia. Some of this funding is targetted towards populations in housing crisis, including 2,500 new units of supportive housing for the homeless, 1,500 units for women and children fleeing domestic violence, 1,750 units for indigenous people over 3 years.

Other related measures are intended to redistribute housing wealth, such as a new speculation tax and higher foreign buyers taxes for Metro Vancouver and other areas, and higher purchase taxes on homes worth over $3 million.

The concensus among housing advocates and anti-poverty movements is that the budget will bring some improvements to the housing crisis for low-income British Columbians. But stretching out the plan over an entire decade means that many will be left waiting for years, and the speculation taxes are likely insufficient to address the enormous housing bubble which has driven working people out of the market.

On the health care front, the elimination of MSP premiums at the end of 2019 will save families $1800 annually (and $900 for individuals), with the revenue replaced by a new employer tax. This measure has sparked an uproar from the corporate sector, which of course never objected to their huge tax breaks during four terms of Liberal government.

The budget increases funding for seniors and residential care, and reduces deductibles for prescription drugs for poor and working class individuals and families. The new Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions receives $322 million over the next three years to support a shift from emergency response to proactive and preventative strategies. Not least, the budget provides new funding for health construction projects and upgrades, and medical and diagnostic equipment. Groups in this sector such as the BC Health Coalition and the Hospital Employees’ Union responded positively, including to a promise to review the controversial “P3″ strategy of the former government.

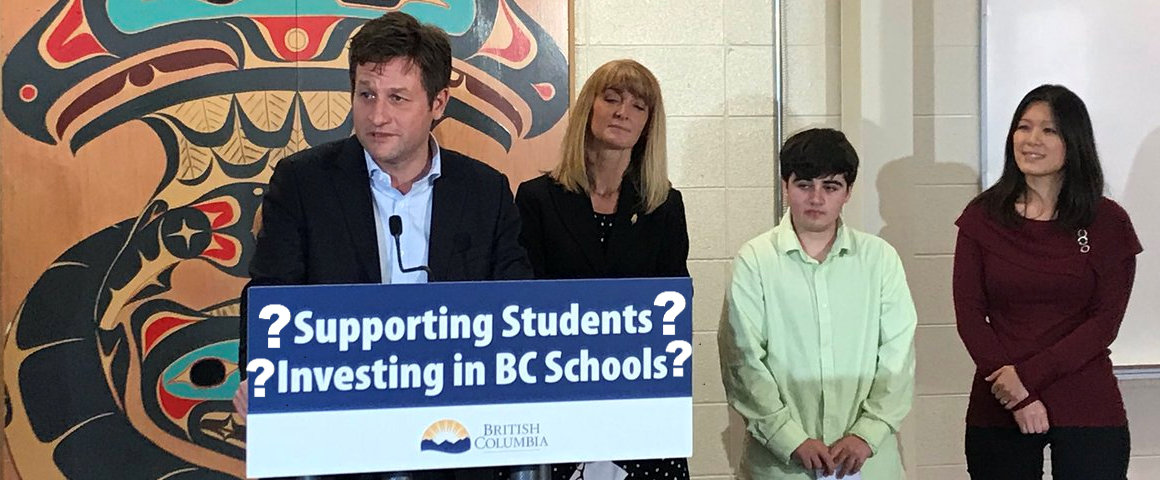

Public education receives less attention, in part because the Horgan government had to move quickly last fall to boost funding in response to the Supreme Court of Canada ruling which ordered BC to reverse years of Liberal cutbacks. While the BC Teachers Federation is positive about the overall direction of the budget, it points out that more funding is still needed for specialist teachers and education assistants to support children with special needs.

The budget increases supports for youth aging out of care, and raises their age of coverage to 26 years, hopefully ending the string of tragic outcomes when youth turn 18 and are suddenly left completely on their own. But there is nothing new for people on social assistance or disability, although these groups did get a small boost in their monthly cheques last fall.

Only $3 million is allocated to monitor employment standards, which is expected to be a problem when the minimum wage increases to $15/hour – but that will not happen until 2021, disappointing the labour movement and anti-poverty advocates. Clearly, the government has not done nearly enough to tackle severe poverty in British Columbia.

Despite some positive changes, much more could have been done to increase revenues by reversing the former government’s giveaways to the wealthy, who reaped an estimated $2.5 billion or more annually from the Liberal policies. But just as with the Site C dam decision, it appears that the NDP backed away from any serious challenge to corporate power, preferring to adopt a package of useful but limited economic and social reforms.