By Bennett Guillaume, in Shanghai

If official media reports are to be believed, Xi Jinping, General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and President of the People’s Republic, recently told the Politburo that a profound understanding of Marxism on the part of the country’s leadership was essential. He warned his colleagues that any abandonment of Marxism would cause the CCP “to lose its soul and direction.”

As the CCP approached its 19th national congress in mid-October, he also suggested that the Chinese people, largely because of the profound social and economic changes their society has undergone in recent decades, are in a unique position to further develop those theories first elaborated by the authors of the Communist Manifesto.

I confess to being puzzled by academics, pundits and ordinary followers of the global scene who casually affirm, as though it were a given, that Beijing has abandoned Marxism and socialism. Perhaps this is an unreasonable reaction to such affirmations, since the reasoning behind them isn’t obscure. China’s is a market economy; there is no doubt about it. The private sector is large and flourishing, generating the bulk of new employment. The country now boasts a vigorous capitalist class, often fabulously rich (and notoriously vulgar in its consumption habits). Inequality, both between regions and social strata, can be striking.

Yet it is undoubtedly worthwhile to listen to what the Party itself says, to consider its own elaborations on the “Chinese road to socialism,” and to study what is actually occurring here. Party thinkers put matters quite simply and in terms that strike me as notably Marxist: the rapid and comprehensive development of the productive forces remains the primary task and the condition for present and future prosperity. The relative equality of pauperism, part of Mao’s legacy, is not a communist vision; rather, decent remuneration according to work and, increasingly, services supplied on the basis of need, require a highly developed material base. And accelerated development is most effectively accomplished through a thorough integration in the world economy, which means wholehearted participation in markets – even as the State drives the process.

The results have been far from trauma-free, of course. But these results include, over the past three decades, the greatest poverty alleviation program in the history of the world, an initiative that has seen perhaps half a billion people rise from destitution. Last year alone, more than 12 million rural citizens of China stepped over the poverty line, according to government statistics.

Even as the Party encourages private enterprise and initiatives from civil society (in the shadow of such slogans as “Small State, Big Society,”) the Chinese public sector remains far from modest. At its apex, and under the direction of the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council (SASAC), there are just over 100 publicly-owned, central-level, non-financial enterprises. Then there are numerous players in banking and finance ultimately held by the China Investment Corporation. Add to this myriad subsidiaries of these just-mentioned entities, along with many thousands of more firms controlled by regional and municipal SASACs and governments, and one begins to get a general idea of the public sector’s reach. And then consider the fact that of 1,624 listed private companies in the country, some 23 per cent name State entities as top, though not controlling, shareholders. (Indeed, this mixed ownership model cuts both ways, as a majority of publicly traded entities effectively controlled by the State also list at least one individual among their top ten shareholders.)

So-called productive sectors where the Chinese State remains dominant or prominent include finance, telecommunications, energy, aviation, engineering and construction and even vehicles and auto parts. And then of course there is the terrain of social service provision – healthcare, education and related fields – in which public entities are leading if not monopolistic providers.

Clearly, what can be expected in coming years is more of the same: continued State and Party control of key sectors alongside an ongoing effort to attract international capital; subsidies for public and domestic private players alike that appear capable of innovating and creating employment; and a well-publicized fight against corruption designed to shore up Party legitimacy and improve economic efficiency. The model is mixed ownership, with the State holding a decisive place in decisive spheres.

Meanwhile, looking beyond its borders, Beijing is placing enormous emphasis on its Belt and Road project, an international infrastructure initiative designed to link the country with markets along the historic “Silk Road.” The plan also involves boosting capacity within the borders of neighbouring and more distant States in which China invests and with whom it trades (more on this, perhaps, in a future article).

And the workers?

Of course, any discussion of State and Party control over socioeconomic life in China leads to additional questions. Most notable is this one: if markets prevail, and if reforms in China have indubitably allowed a capitalist class to reemerge (not to mention a State-linked elite with considerable income and privilege), what about the workers? Specifically, if socialism and communism are to remain on the agenda, must the working class not have its own self-defence organizations, whose effectiveness depends precisely on their democracy and autonomy? This is a theme partially recognized in theory, by the way, by the All China Federation of Trade Unions – and even to some extent in practice. But it is a work in progress, to say the least. Suffice at this point to note two things: Chinese workers are often not shy about taking action if they are ripped off; and when ripped off, they are often disinclined to rely on their official representatives.

Impressions of Shanghai

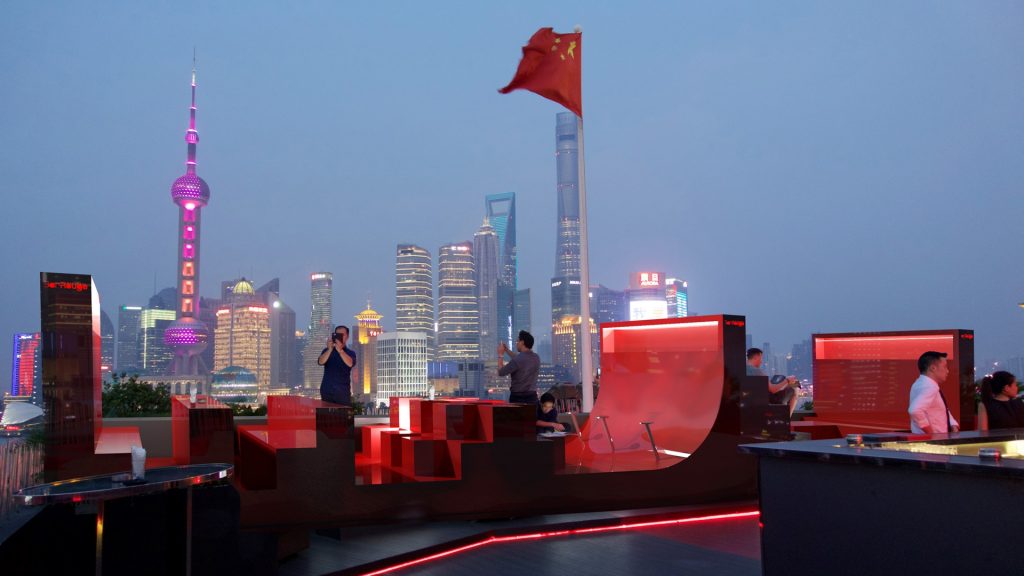

Having recently arrived in Shanghai, I think that some anecdotal impressions might be appropriate to this article. This most populous city in the world’s most populous State strikes the newcomer with its extraordinary energy, obvious prosperity and cutting-edge ambiance. Purchases are accomplished in most stores with an app (never mind that sheet of old technology known as a bank card, though it remains an option). Huge towers are ubiquitous, as others who have travelled here will know. This a place built to the clouds.

Public transit is outstanding, in terms of reach, performance and affordability. One gets the distinct impression that if the Shanghainese are buying and driving new cars, and they are in alarming numbers, it is not due to a need to get around; the mammoth subway system will deliver one anywhere.

Also impressive from a public transit point of view is that network built around a considerably simpler vehicular technology. Clusters of brightly coloured bicycles abound. For a paltry sum you can take a bike from anywhere and leave it anywhere, provided you lock it up. One would be tempted, on this basis alone, to call Shanghai a cyclist’s paradise – except for the fact that car and scooter owners can be lethal in their driving styles. To be sure, crossing the street as a pedestrian is possibly the riskiest act one can undertake in this mega-city of around 25 million.

Nor is the sharing economy limited to bikes. In this region of regular rain, umbrellas may also be had in subway stations. Just remember to return yours to the rack.