Tuesday, February 4th of 1992 was going to be just another ordinary day for Venezuelans. From early morning hours the traffic in large cities like Caracas, Maracaibo, Valencia and Maracay would get congested for most of the day. Students would be going to school. It would be just a normal workday for those who were lucky to have a job.

Not many knew that Carlos Andrés Pérez, the president of Venezuela, had been away attending the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, and was due to return on that day if not the night before.

The majority of Venezuelans did not care much about an event that had no immediate relevance for them. Other concerns affected them directly: a stagnant GDP growth, high unemployment, low wages, rampant poverty levels triggered by the IMF neoliberal economic reforms adopted by the Pérez government and the country’s corrupt political establishment. Pérez himself was eventually impeached on charges of embezzlement in 1993. He was sentenced to prison in 1996. Then sentenced again in 1998 on a separate corruption case, but he fled to Florida where he later died.

However, that February 4th Venezuelans woke up to a different day. A day that put an indelible mark in the history of Venezuela.

Lieutenant-Colonel Hugo Chávez Frías had built for years among many of his fellow soldiers the conviction that a rebellion was not only necessary but also possible in Venezuela. His ideals were those that motivated the Liberator, Simón Bolívar, to fight for an independent Latin America. Chávez believed that the “Bolivarian project”, as he called it, belonged to the 21st Century. The project had not been completed, since Venezuela and the rest of Latin America were still not independent and were in reality under a neo-colonial domination, albeit by another country.

Chávez said later that since the beginning of the 20th Century “it’s been the same system, in economics and politics, the same denial of human rights and of the right of the people to determine their own destiny… Venezuela was suffering a terminal crisis, ruled by a dictatorship dressed up in democratic clothing.” [1]

He had assessed that there was great discontent among Venezuelans, and came to the conclusion that the time was ripe for a military rebellion that would be fully supported by the population.

Chávez and his close collaborators worked out a detailed plan with military precision that involved the full control of Caracas, the capital city, with battalions, including the air force, coming from Maracay and Valencia. Other large cities like Maracaibo and Barquisimeto would also be taken. Ultimately TV stations would broadcast nationally Chávez’s pre-recorded speech to the population explaining what was happening and asking them to join the rebellion.

After eliminating other alternative dates for the action, the best opportunity was the night of February 3rd to 4th. Confirmation came that the president was returning from Davos the night of February 3rd. He would be taken prisoner by surprise at the airport and taken to Chávez’s rebel headquarters at the Military History Museum in Caracas. Immediately a National General Council would be formed with military and civilians in order to elect a new president. That was the plan.

Alas, no masterful plan can survive a treasonous action. A traitor leaked the plan and the president was tipped off, avoiding apprehension at the airport. The rebel air support also failed, and after a few hours the rebellion had no chance of succeeding. In the early morning of February 4th, Chávez surrendered to avoid bloodshed.

What followed from this initial defeat is the stuff of revolutionary legends that are born from a timely combination of circumstances and presence of mind.

Not knowing that the main objective in Caracas was not achieved, the rebel forces in Valencia, Maracay and Maracaibo were making advances, controlling the cities with the help of civilians. Chávez weighed the risks and decided that it was futile to continue, since eventually they would be captured and possibly killed by government forces. He suggested to his captors that the only way of communicating with his supporters and asking them to surrender was via a live TV broadcast. They agreed, failing to realize that the whole of Venezuela, now on alert, would have an opportunity to see and hear this audacious Bolivarian soldier.

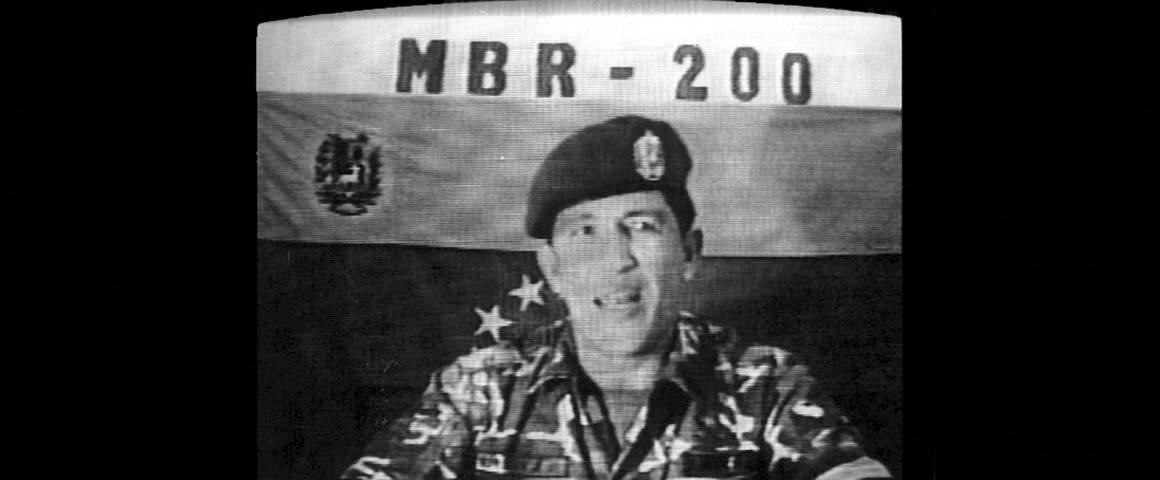

In full military fatigue and red beret of the paratroopers, self-assured and in control, Chávez appeared on live national TV that same morning. While his words called his comrades to surrender, his message was a promise that this was not the end of the struggle. He said in part, “Comrades: Unfortunately, for now, the objectives that we had set for ourselves have not been achieved in the capital. That’s to say that those of us here in Caracas have not been able to seize power. Where you are, you have performed well, but now is the time for a rethink; new possibilities will arise again, and the country will be able to move definitively toward a better future.” [2]

Although founded ten years before, Chávez’s “Movimiento Bolivariano Revolucionario” had its baptism of fire in the ashes of a failed coup. However, Chávez’s real successful coup on that February 4th materialized – he was able to reach out to the population and deliver a seemingly encrypted message conveying his real intentions. Venezuelans took notice and did not forget. More than 80% of Venezuelans supported the rebellion.

Reminiscent of Fidel Castro in his famous recognition of José Martí as the author of another attempted takeover of the Moncada military barracks in Cuba, at the end of February, still captive, Chávez declared in an interview, “The true author of the liberation, authentic leader of this rebellion is General Simón Bolívar.” He remained faithful to his Bolivarian mission reflected in the official renaming of the country as the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela.

Having participated in the multi-party electoral process of 1998, on February 2, 1999 Hugo Chavez was sworn in as President. Breaking protocol, Chavez pronounced his own pledge: “I swear in front of God, in front of the homeland and in front of my people that over this moribund constitution I will push forward the democratic transformations that are necessary so that the new republic will have an adequate magna carta for the times.” [3]

He was true to his own words.

[1] Bart Jones. The Hugo Chavez Story – from Mud Hut to Perpetual Revolution. Random House 2008, p. 136.