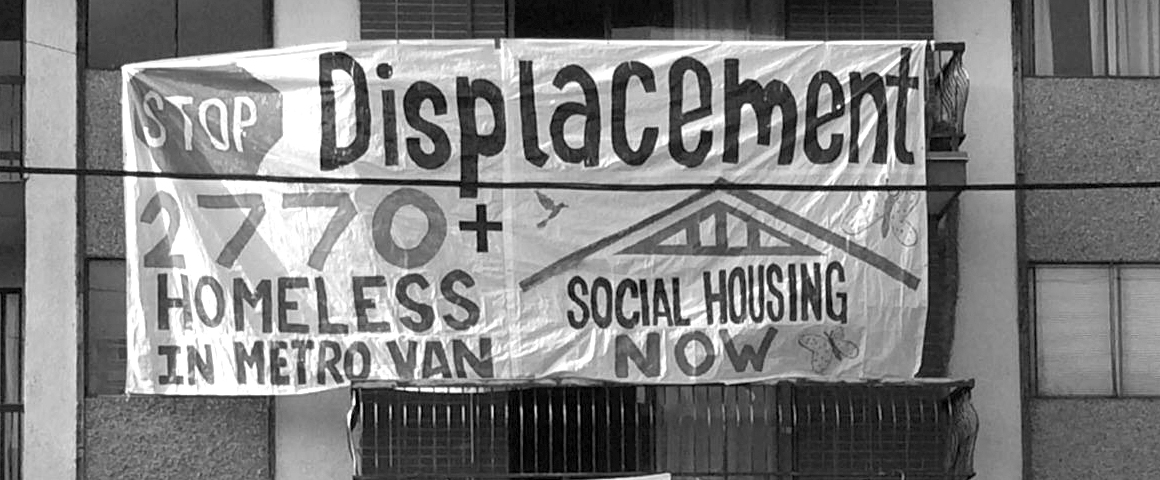

With public anger growing against the escalating housing crisis in Metro Vancouver, the recent occupation of a walk-up apartment in the Metrotown area of Burnaby has taken the struggle up another notch.

On July 9, activists from the Stop Demovictions Burnaby Campaign, the Alliance Against Displacement and allied groups occupied an apartment slated for demolition at5025 Imperial Street, near Metrotown Mall. At 5 am on July 20, about 20-25 RCMP officers smashed windows to enter the building and remove the occupiers. No charges were laid, but the participants were ordered not to enter buildings on that block, which is being flattened for new condo towers. The organizers, who have been working with tenants in the area for the past two years, say the same tactic will be used at another nearby building as part of an ongoing campaign to resist the destruction of relatively affordable housing units.

In recent years, similar struggles have taken place in Vancouver, particularly in and around the Downtown Eastside neighbourhood which is undergoing massive gentrification. Housing prices – and profits for developers – have skyrocketed, and the tide of demolitions and condo towers is now sweeping east into Burnaby and beyond.

Both cities have councils dominated by NDP supporters. Vision Vancouver, and the Burnaby Citizens Association have different outlooks on how to address the housing crisis in the region, but both receive huge donations from developers for their election campaigns.

In Vancouver, Mayor Gregor Robertson and Vision took office in 2008 promising aggressive action to eliminate street homelessness by 2015, and to use urban densification as a tool to create “affordable” housing. That term eventually came to mean any housing which a buyer can pay. Some initial successes were gained by expanding shelters, easing restrictions on secondary suites, and other policies. But as housing costs go through the roof, fewer and fewer truly affordable rental options remain. There are now more homeless people on the streets of Vancouver than ever, and thousands of families have left in search of cheaper housing in the suburbs or other parts of the province.

Next door in Burnaby, Mayor Derek Corrigan and his long-time BCA majority argue that housing is the responsibility of the provincial and federal governments, which have far greater powers of taxation and resources to invest in low-income, cooperative and other forms of affordable housing.

On that logical basis, the BCA has rejected Vision-style interventionist strategies, with one important exception: backing the push by developers to keep rezoning neighbourhoods for condominiums. In both cases, the result has been a faster pace of destruction of existing housing stock rented by working class families, especially indigenous people and racialized communities, and people on social assistance and disability.

Governments at all levels are looking for easy scapegoats for this situation, with foreign speculators a favourite target. But the provincial government and municipalities also bring in huge revenues from the boom, making them reluctant to take action, especially since any decline in the housing price bubble could have negative impacts on the economy of British Columbia and even Canada.

Most of the debate in the corporate media has focused on the unaffordability of homes and condos. Detached houses now sell for an average of nearly $1.3 million in east Vancouver, and over $3 million on the upper-income west side, far beyond the reach of most people.

But the real crisis is hitting those who could never afford the deposit on a $400,000 condo, let alone a house. Ground zero for this social disaster is now the Metrotown area, where the mega-mall is surrounded by blocks and blocks of relatively affordable walk-up apartments. Many of these decades-old buildings are falling into disrepair, but could easily be upgraded. Instead, the bulldozers are knocking down one after another, with the cranes putting up new high-rises visible in every direction.

On May 16, the Stop Demovictions Burnaby Campaign presented Burnaby City Council with a detailed report on the demovictions crisis. “A Community Under Attack” documents the effects of displacement on renters facing eviction.

Three of those buildings are being “demovicted” by corporate developer Amacon in order to build a 30 storey condo tower. The tenants were understandably terrified for their futures, and that fear has been intensified by the subsequent evictions and cut-off of hydro and water services.

The Stop Demovictions Burnaby Campaign presentation was based on a door-to-door survey of households in fifteen buildings being demovicted from the square block north-east of Dunblane and Imperial Streets in Metrotown.

The survey found that about 73% of apartments were one-bedrooms, but 28% of units had three or four occupants. With an average of two people per apartment, nearly five hundred people will lose their homes in the Dunblane demovictions. Currently, in Metrotown, 684 apartment units are scheduled to be demolished, affecting about 1,400 people.

The survey found that 55% of tenants pay more than 30% of their incomes to rent, an indicator of being at-risk of homelessness. About one-quarter of residents have only lived in their apartment for one or two years, and these uprooted tenants tend to come from other demolished or renovicted buildings. One-quarter are long-term residents who have lived in their apartments for five to ten years. Largely seniors or people on pensions or disability, they will be hard-hit by a forced move into a much more expensive housing market.

Those evicted residents who had found a new place in the Metrotown area were going to be paying 25% more for rent (about $250 more per month). But 62% had still not found a place to live, only two or three weeks prior to eviction day. Most planned to crash on friends’ couches, live in a camper, or move in with family or with a partner with who they would otherwise not cohabitate. Some were filing BC Housing applications, despite waitlists as long as ten-years for social housing.

The survey found “not one single person who reported receiving support, a visit, or any contact from representatives of the City of Burnaby, an advocate, or service provider.”

The Community Under Attack report made several recommendations: a moratorium on rezoning properties currently used as residential rentals; municipal action to find housing for those displaced by demovictions; use city funds to buy a building for emergency housing; cancel Burnaby Council’s proposed “downtown” Metrotown plan, and begin a community planning process that involves residents most vulnerable to displacement; and dedicate existing City-owned lands for social housing.

(For a copy of the report, email organize@stopdisplacement.ca, or download it at http://www.stopdisplacement.ca/burnaby/)

In response, Mayor Corrigan said “Thanks for the report, we’ll send it to staff for their consideration, and they will engage Council in a conversation and a report will be issued, which we’ll pass along to you.”

Not surprisingly, such comments by the Mayor and the BCA, and the support for Corrigan coming from NDP MLAs and MPs, have been viewed as dismissive and even hostile by residents facing evictions. Some observers speculate that the BCA simply doesn’t care, since voter turnouts in this neighbourhood are usually low. But by choosing to align with developers, both the BCA and Vision Vancouver risk alienating the NDP’s traditional working class voter base just months before the May 2017 provincial election.