By Robert Navan and Seán Edwards, Socialist Voice (Communist Party of Ireland)

When Obama declared Venezuela to be a threat to the United States he wasn’t being absurd. He meant, of course, a threat to US hegemony in the region.

The Bolivarian Revolution in Venezuela was the greatest challenge to that domination since the Cuban Revolution in 1959. The ruling oligarchies in Latin America always needed to ally themselves with the imperialist power, not being strong enough to rule on their own. Ever since Hugo Chávez’s election displaced them from office the old Venezuelan political regime strove to overthrow the government by any means, always in alliance with the United States.

With the death of Chávez, and the absence of his charismatic personality, the right-wing opposition saw an opportunity to go on the offensive. The election of Nicolás Maduro was followed immediately by a campaign of street violence instigated by the right, repeated the following year.

When this failed in its objective, the opposition forces concentrated on economic sabotage, manipulating currency, hoarding necessary foodstuffs to create shortages, smuggling state-subsidised commodities abroad to be sold at an enormous profit, and driving inflation into an upward spiral. This caused considerable hardship in working-class communities.

Neither Nicolás Maduro nor Hugo Chávez before him managed to apply an effective policy to protect the currency or to stem the flow of capital abroad. An estimated $100 billion has been moved out of Venezuela since the election of Chávez. While the effect of this was cushioned by the high price of oil, it was still a huge loss to the economy, and the bourgeoisie always chose to squirrel their profits abroad rather than invest in Venezuela.

The currency controls introduced by the government were generally easily circumvented, and sometimes made matters worse. Likewise, the measures taken to counter the hoarding and speculation proved inadequate—even the closing of the border with Colombia to stop the smuggling. President Maduro at one point held talks with the Chamber of Commerce, which had no interest in any settlement, only in intensifying their economic campaign.

The Communist Party of Venezuela and others have long advocated a state monopoly of foreign trade to prevent the fraud and manipulation, as all the less radical measures had failed.

Now, for the first time in seventeen years, Venezuela will be ruled by a right-wing government, following the success in National Assembly elections on 6 December of a coalition that goes by the name Mesa de la Unidad Democrática (Round Table of Democratic Unity). As suggested by the name, this is not a unified political party but more a splintered opposition coalition that throughout its existence has been plagued by factionalism; nevertheless these divisions were successfully papered over to present a united front to the electorate. It is expected that when the new assembly sits, these divisions will reappear.

Among the coalition members there are extreme right-wing elements who are already trying to stop President Maduro completing his term of office, which is not due to end until April 2019. To do this they could try to suspend the constitution. This move would prove very unpopular among much of the general public and could lead to civil unrest. The constitution was written during the presidency of Hugo Chávez, following a huge consultative process with all sections of Venezuelan society, and to have it suspended could be seen as an insult not only to Chavistas but to all sections of the people. Venezuelans from all sides (except the extreme right) are proud, and rightly so, of their constitution.

Another option that is available under the constitution is a presidential recall referendum, which can be initiated three years into the term of office. That option could be exercised in April this year, but there’s no guarantee that the vote would be carried.

The opposition is not made up only of extreme right-wing elements: it includes centrists and left–of-centre members. The more sensible groups could be classed as “gradualists,” and if they emerge as leaders there may not be an immediate frontal assault on the gains of the revolution; rather, it would happen stealthily and over time.

So far, unfortunately, most noise has been heard from the extreme right-wing elements. An Irish journalist described this section of Venezuelan society as “one of the most unpleasant set of people he had had dealings with anywhere in Latin America.” These are the people who led the civil disturbance that resulted in the death of more than twenty people and the wholesale destruction of state property. Health clinics were among the sites that were targets, as with many Cuban doctors working in them, they were seen as one of the main gains of the revolution.

An opposition politician, Henrique Capriles Radonski, has already made statements about ending the Petro-Caribe initiative, which since 2005 has provided neighbouring Caribbean countries with much-needed oil at significantly preferential repayment rates. He has also cast doubts on the future of the Venezuela-Cuba project known as the Bolivarian Alliance for the People of Our Americas (ALBA). This promotes direct non-monetary and fair-trade relations among its eleven member-states, including the exchange of Venezuelan oil for the training of medical personnel by Cuban doctors.

With the continuing fall of oil prices internationally, the incoming government will still have a major task on its hands in trying to improve the lot of the ordinary person. Add to this the fact that previous right-wing governments in Venezuela were probably the most venal in the world and considered assets such as the state oil company to be their own personal financial kingdoms. We may see the oil that for the last seventeen years has been used to facilitate spending on social schemes now being used to provide lavish condos in Miami and other such items for a minority of the population. This was the situation in pre-Chávez times.

It’s worth remembering that Venezuela has already experienced some of the worst excesses of neo-liberalism. In 1988, after a similar fall in oil prices, the government of Carlos Andrés Pérez was elected on an anti-neoliberal platform but went on to implement such a policy, as recommended by the International Monetary Fund. This included privatising state companies, tax reform, reducing customs duties, and diminishing the role of the state in the economy.

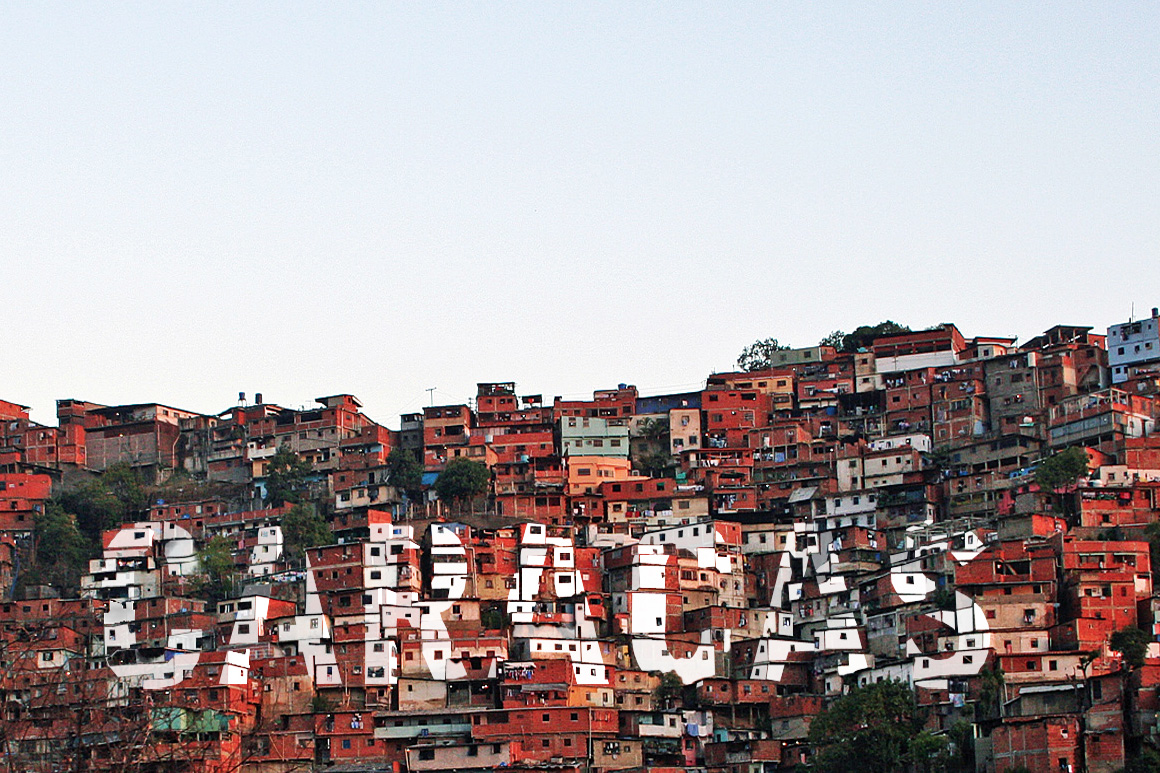

As a direct result of these measures there was widespread rioting and a brutal repression that led to death of more than two thousand people. This period in Venezuelan history is referred to as the “Caracazo” (the “Caracas shock”), which refers to the fact that most of the rioting and subsequent deaths occurred in the Caracas area. This bitter experience contributed to the emergence of Hugo Chávez and the Bolivarian Revolution.

What now for the left in Venezuela? Well, as the saying goes, “the genie is out of the bottle.” During the years of the Bolivarian Revolution the people, particularly the poor, have seen massive progress in the areas of health, education, housing, and nutrition. Any immediate attempts to reverse these policies would meet with popular resistance.

The gains of the Bolivarian Revolution will be defended. The parties, trade unions and social organisations organised in the Chavista coalition, known as the Gran Polo Patriótico (Great Patriotic Pole), face a daunting task of self-criticism and reorganisation. They have the potential to mount a successful defence and bring Venezuela back onto the path of progress.